When Douglas Percy Bliss, Director of the Glasgow School of Art, wrote quite pointedly that Alan Fletcher 'gave us more trouble than any other student in my time', he was likely not exaggerating. Fletcher, who had just died in an accident at the age of 28, had spent his short life pushing against the grain.

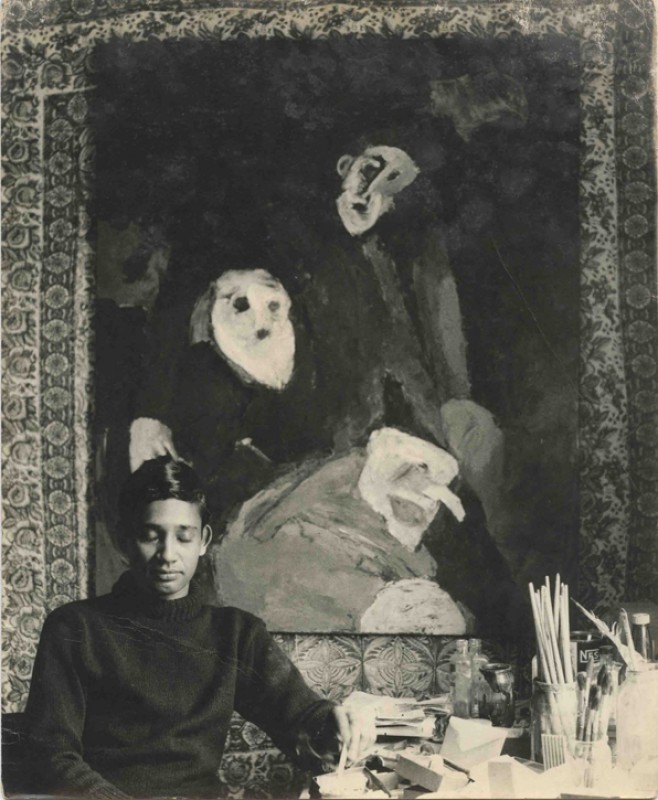

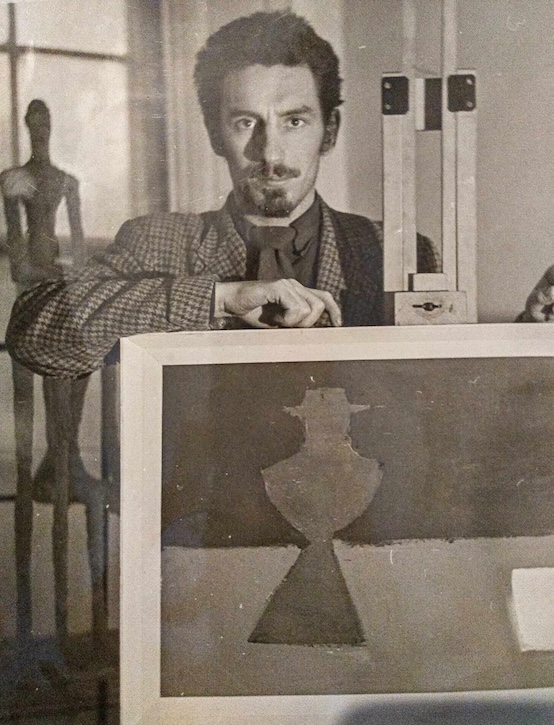

Alan Fletcher with 'Still Life with Lamp and Cup', c.1957

At art school in 1950s Glasgow, Fletcher was well-known for his clear talent and his out-and-out opposition to the teaching. A problem student as well as a very charming one, he left his teachers exasperated. 'And we put up with this', Bliss wrote, 'in the hope that he would prove to have unusual abilities'.

During his tragically short, comet-like existence, the quality and integrity of Fletcher's strikingly modern work eluded the conservative art establishment in Glasgow. Fletcher showed glimpses of an extraordinary body of work in exhibitions far beyond his native city. If his abilities were less 'unusual' when placed on the international stage, they were no less remarkable.

Still Life with Lamp and Cup

c.1957

Alan Fletcher (1930–1958)

Born into a working-class Glasgow household in 1930, Fletcher's formative years were spent in the shadow, then the sweep, of the Second World War. From a home at the heart of the city, he watched events unfold at home and abroad – all too aware of the Blitz on the River Clyde as well as the developing drama of the War in Europe.

Just streets away from his family home, the Glasgow School of Art also bound Fletcher's city to the world: Mackintosh's Art Nouveau masterwork was a European statement in itself. When Fletcher entered the art school in 1951, after his National Service, he was a talented, intelligent if impulsive 21-year-old: a proud Glaswegian with an eye on the wider world.

Fletcher, guided by an expansive outlook, found the art school's training insular and inflexible. His ability to master academic technique, which came easily, did little to settle a restless creative spirit, and his strong-willed reputation alienated the teachers in the Drawing and Painting Department. The artistically adroit Fletcher was nevertheless prepared to appease his teachers with traditional painting now and again.

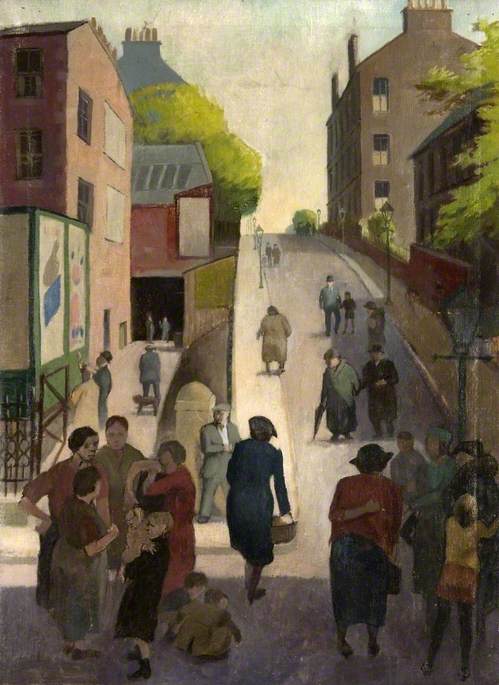

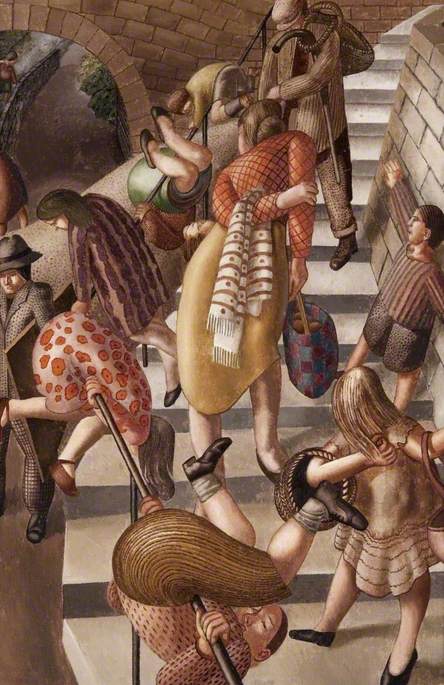

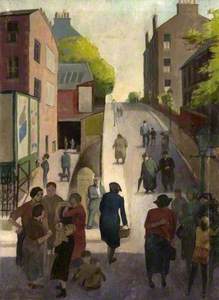

His painting of Glasgow's Hill Street is unusually conservative, probably painted for an easy passage through art school. But Fletcher is quietly defiant in his work: his impossibly sleek figures owe little to the lessons of the life drawing class. Instead, the subtle distortions reflect the attraction of Stanley Spencer's work: Spencer had spent time in Port Glasgow during the War.

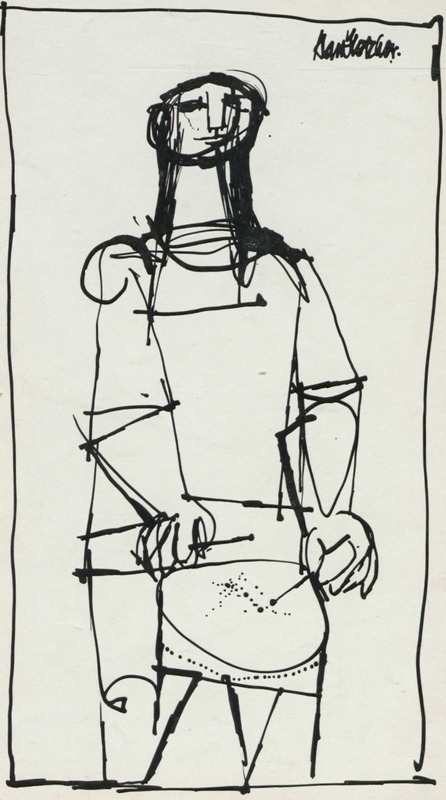

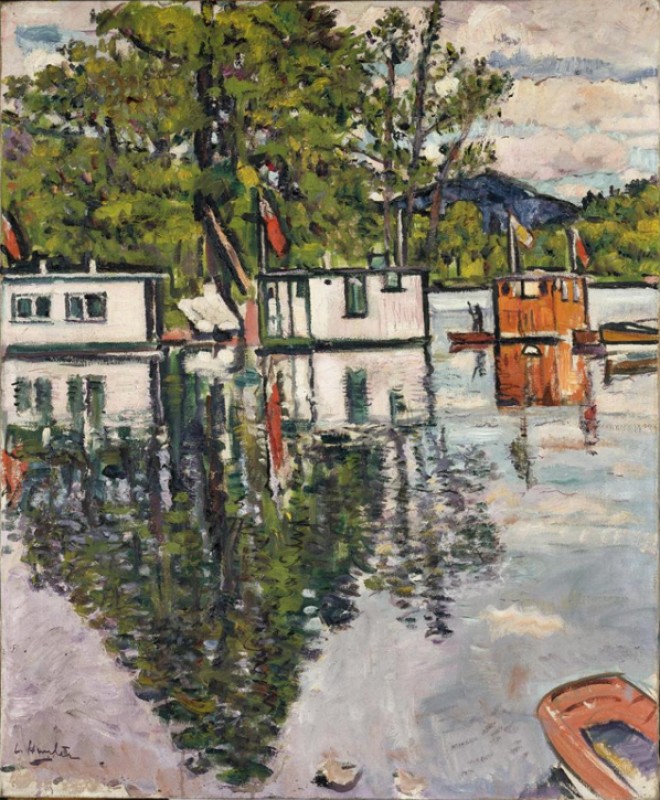

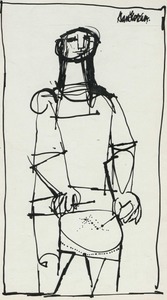

The Second World War had an electrifying effect on Glasgow's art scene. The arrival of talents like Jankel Adler, Josef Herman, John Duncan Fergusson and Margaret Morris, as well as Spencer, stimulated exciting work with an anti-academic, European flavour. Even as the War gave way to the austerity of the 1950s, a certain receptiveness to new continental ideas hung in the air. Fletcher's drawing Drummer shows at a glance the indirect and lasting influence of Adler in Glasgow.

Hommage à Naum Gabo (Homage to Naum Gabo)

1946

Jankel Adler (1895–1949)

Beyond this legacy, Fletcher found ways to absorb contemporary European and American culture, even as a poor art student in 1950s Glasgow. Magazines like Vogue, saved or stolen, opened his eyes to cutting-edge developments in art and design. Cheap tickets to the pioneering Cosmo cinema, where Fletcher saw films like Clouzot's Mystery of Picasso, left him besotted with the modern European masters.

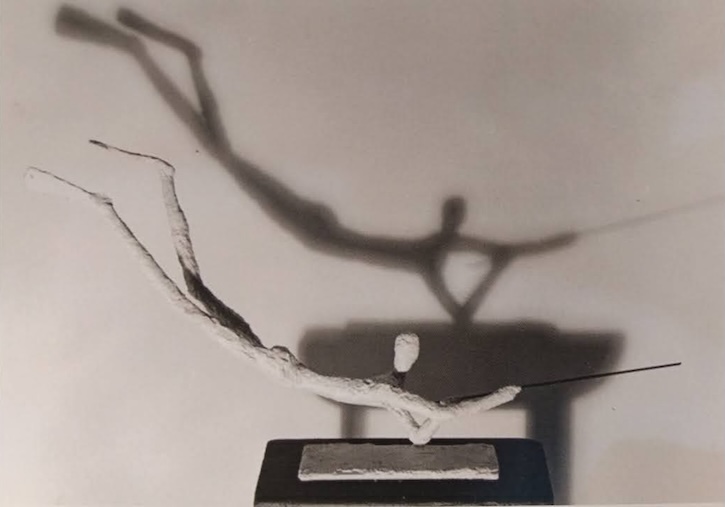

When Fletcher was denied entry to the Painting Department and went on to specialise in Sculpture, a close relationship with his Estonian-born teacher Benno Schotz further stirred his enthusiasm for the world outside Glasgow. Sculptures like Underwater Hunter could have been modelled in a Parisian atelier.

Underwater Hunter

sculpture by Alan Fletcher (1930–1958)

In Underwater Hunter, Fletcher clearly had Alberto Giacometti on his mind, but the idea grew from the sight of swimmers in the local pool. In Fletcher's work, Glasgow meets the world.

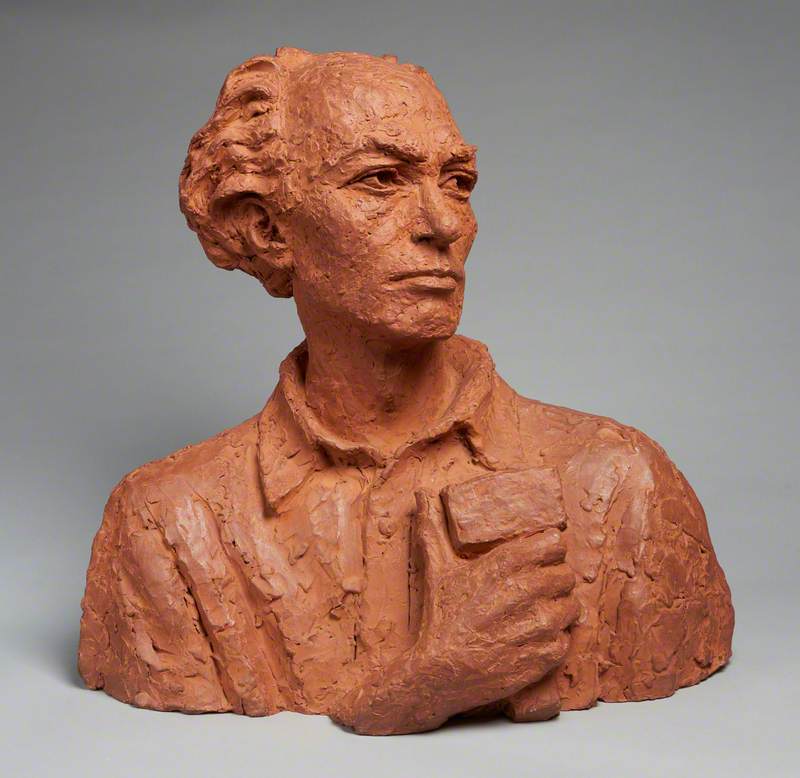

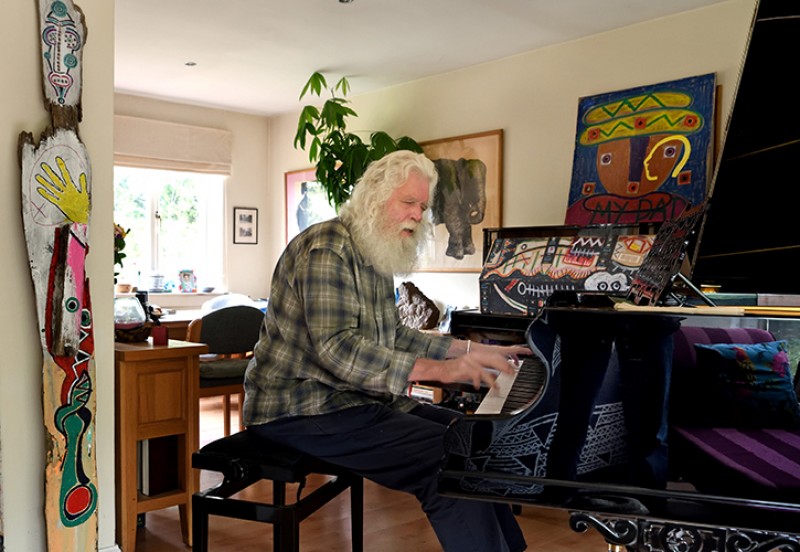

Fletcher's art school career lasted six years in total, not four, because of what Schotz generously described as his 'advanced views in art'. His 1957 bust of Fletcher, modelled in the year he gained his Diploma and became Schotz's assistant, reflects something of Fletcher's bright, creative intellect and rakish good looks, not to mention the close relationship he shared with his mentor.

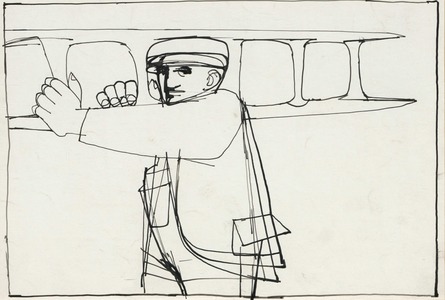

Alan Fletcher with Euphonium

(Alan Robert Tregoning Williams Fletcher, Artist, 1930–1958) 1957

Benno Schotz (1891–1984)

While Hill Street shows Fletcher taking on an academic challenge, the back of this painting shows that his individual vision was developing rapidly.

Fletcher's life model might appear unfinished, but in his deliberately crude touch, he is seeking to intensify a haunting presence. Fletcher reduces the subject to its essence, rejecting any embellishment, seeking a basic artistic truth.

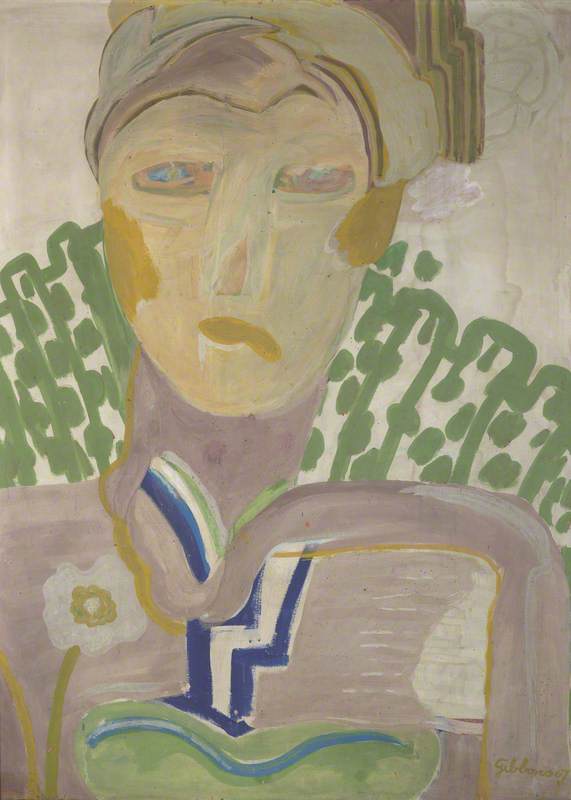

Young Girl shows Fletcher driving the likeness of his then-girlfriend, the artist Carole Gibbons, almost to the point of abstraction.

An extremely unusual painting for post-war Glasgow, it reflects Fletcher's serious engagement with the work of the French artist Nicolas de Stael. This work is a striking artistic statement about the possibilities of abstract painting, but Fletcher, ultimately a figurative artist, also achieves a miraculously recognisable likeness.

Fletcher's handling of paint breathes life into his figural paintings. In Don Quixote, he dehumanises the figure by paring back all the signifiers of personality, reducing and distorting.

But Fletcher's dynamic, even aggressive application of paint animates the Don; the strength of his gestural touch lends this monstrous figure an immense presence which is almost nightmarish.

Fletcher's man on horseback – seemingly in control but blind, bound to be carried away – is a clear metaphor for the human condition in the Cold War years, when mankind very nearly lost control of a terrifying force

Fletcher extends the metaphor in his 'Man on Wheel' series (private collection), which shows figures balancing on that symbol of human progress, only to fall to their doom on realising it is also an agent of self-destruction: the wheel might be the nuclear weapon.

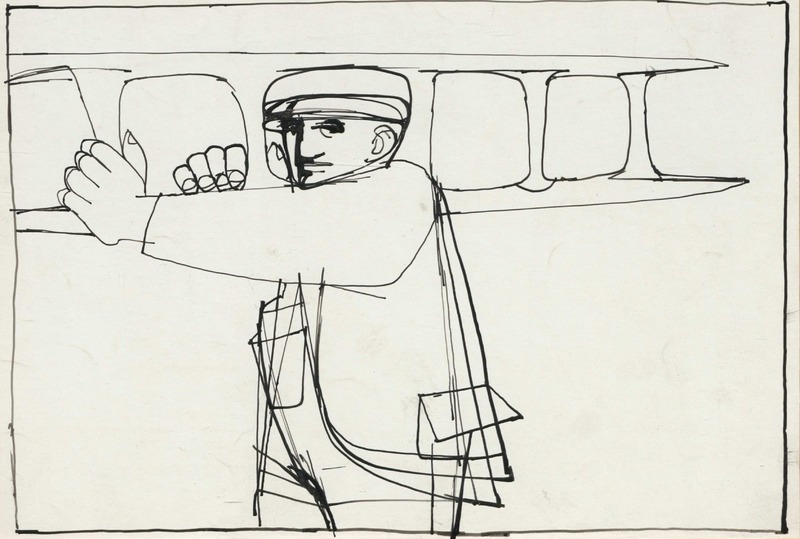

Balance runs through Fletcher's body of work, as in Man with Ladder. It might be an image from industrial Glasgow, but it is also his response to a contemporary, international visual language which grew from the anxieties of the day.

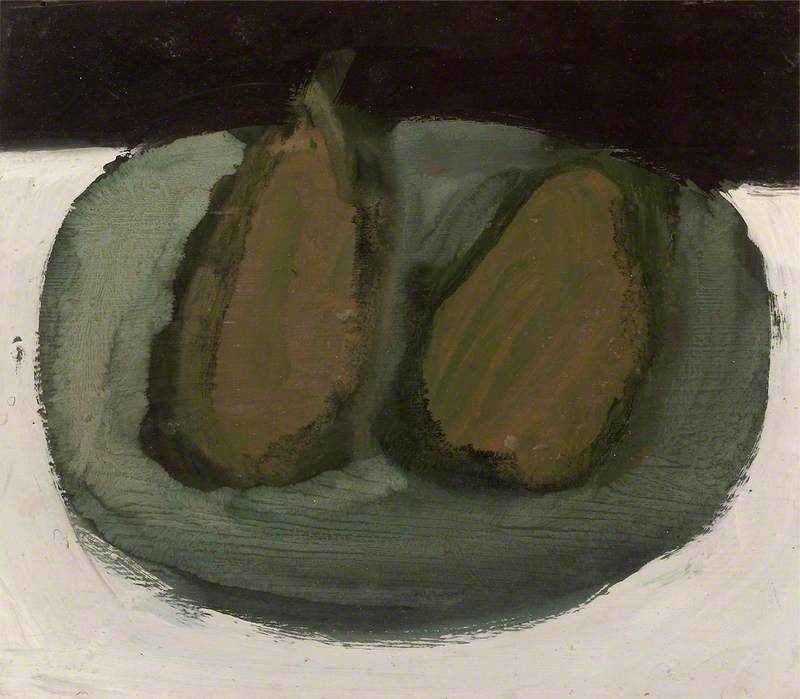

Fletcher's still lifes are among his most powerful works. He interrogates everyday objects, like pears and oil lamps, almost obsessively, reducing their shapes so dramatically that the texture of the paint itself appears to become the subject. Just as he smeared cement on his Underwater Hunter, he builds up the surfaces of paintings like Lamp on a Table, which has been loaded so heavily that it has succumbed to gravity as well as age, and large pieces have fallen away.

By placing such emphasis on the materiality of the paint itself, Fletcher makes a conscious attempt to affirm what is real. In Lamp and Pear, a tactile treatment – the sticky, lumpy texture of the black paint on the lamp's base – appeals to the viewer's senses for an immediate response.

His still lifes are attempts to turn shifting, subjective reality into concrete, objective fact: something physical, not fleeting, in which we can all share. These works might be an artist's attempt to exert control in a brave new world which appeared to be spinning out of control.

But Fletcher's vision is not straightforward, integrated or comforting: he presents the essential ambiguity of a troubled modern world in a small but complex body of work. Sheep's Head, which should qualify as a very still life, appears strangely animate, buzzing with the same energy which surrounds the Young Girl. Is it living, dead, both or neither?

The picture, of course, speaks for itself; Fletcher addresses reality, often dizzyingly bleak, in a visual language marked by strength, maturity and originality.

Sheep's Head, painted in the year that Fletcher first visited mainland Europe, might be a memento mori: in 1958, he died in an accidental fall in the yard of his student hostel in Milan, aged 28. The extraordinary and precious body of work he left behind, so strikingly distinct from that of his contemporaries, constitutes a channel which shows the currents of modernism flowing into postwar Scotland. His 'unusual abilities', once damned with such faint praise, built a legacy which marks Fletcher out as one of the most compelling talents of his generation.

Douglas Erskine, art writer and researcher

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust