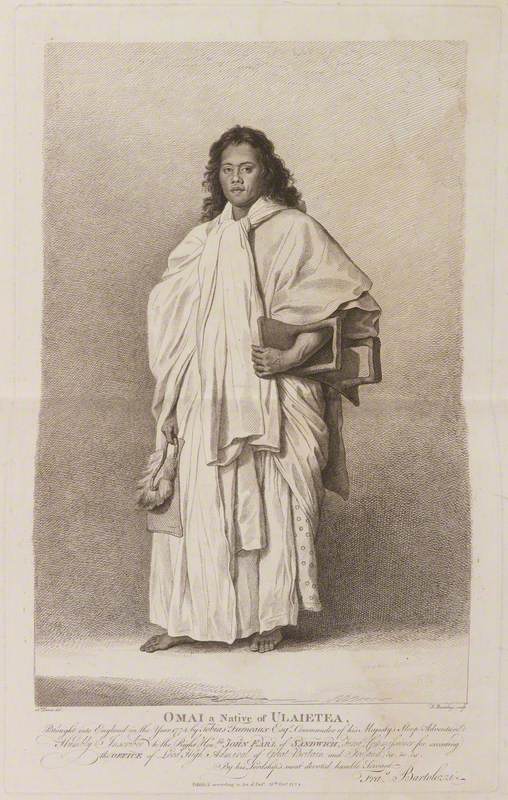

Omai or Mai (pronounced May-e in Tahitian) (c.1753–1779) was the first Polynesian visitor to Britain. He had travelled from Huahine, one of the Society Islands, on board the Adventure, the sister ship to the Resolution, on Captain James Cook's second expedition to the Pacific, arriving in Plymouth in July 1774.

Joshua Reynolds's famous portrait of Mai, painted around 1776, has now begun a national tour, travelling from the National Portrait Gallery to Cartwright Hall as part of Bradford's City of Culture programme (until 17th August 2025) before visiting Cambridge and Plymouth. You can find out more about this display on Bloomberg Connects, where you can also listen to Tahitian academic and curator Milani Ganivet discuss Mai.

'Mai by Sir Joshua Reynolds', Mililani Ganivet, 2024 © National Portrait Gallery, London

From a Polynesian perspective, the great lengths of tapa cloth that Mai is shown to wear in Reynolds's portrait indicates his high status. As Miriama Bono, former director of Te Fare Iamanaha (Museum of Tahiti), explains in an audio on Bloomberg Connects, only a member of the ruling class, the Arioi, could wear tapa of such fine quality.

'Mai's Clothing', Miriama Bono, 2024 © National Portrait Gallery, London

From a European perspective, these clothes would have carried more classical associations, reminiscent of togas worn by ancient Greeks and Romans. There is also a classical reference in the way that Mai stands, with his hand raised as though on the point of speaking, typical of the adlocutio pose adopted by Roman orators in antique sculpture.

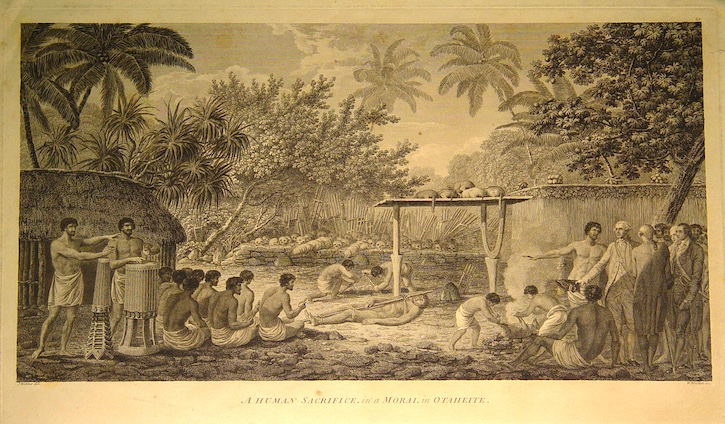

Cook strikes a similar pose in an image from the account of his third voyage, his raised hand communicating his moral indignation at the scene before him. One of the objectives of this third voyage was to repatriate Mai, who is shown in the crowd behind Cook, wearing European clothes, though without a wig.

Note the sword he carries, possibly the same one that George III gave him when they met in Kew Palace in the company of Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander. Banks and Solander, the naturalists who accompanied Cook on his first voyage, regularly chaperoned Mai on his many excursions around London and across England during his two-year stay.

Webber's image is unusual in its depiction of Mai as a cross-cultural figure. In contrast, Native American visitors to Britain are regularly portrayed as figures of what historian Richard White calls 'the middle ground', indicating processes of transcultural negotiation. The Mohawk warrior Joseph Tayadaneega, or Brant, was always depicted wearing both European and Native American clothes.

In George Romney's 1776 portrait (now in the National Gallery of Canada), as well as a feathered headdress, he wears the silver gorget, or chest plate, gifted to him by King George, indicating his role in securing Britain's military alliance with the Six Nations against the rebellious American patriots.

In Reynolds's portrait of Mai, in contrast, there is no explicit reference to cultural exchange. Critically, too, Mai is shown unarmed. A martial depiction of the figure would have contradicted the image the British had of the Society Islands as a peaceful territory.

The truth, however, was that it was far from peaceful. As a child, Mai had fled his native island of Raiatea, after it was taken over by a force from Bora Bora. In fact, the reason Mai chose to board the Adventure was that, like Brant, he hoped to secure military support from the British, hoping to return to his homeland, armed with muskets and cannons, and oust the forces from Bora Bora.

The British had no interest in making such an alliance. Instead of a warrior, Banks and Solander introduced Mai to their friends as a figure of intellectual curiosity. The novelist Frances Burney described him as a 'perfectly rational and intelligent man, with an understanding far superior to the common race of us cultivated gentry'.

Omai

(after Nathaniel Dance) published 1774

Francesco Bartolozzi (1727/1728–1815)

However honestly felt, Burney's admiration for Mai exhibits a distinctive trend in Enlightenment thought, reflected in the writings of French philosophes, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Denis Diderot, in which Tahitian society was used to criticise the codes and principles of the present-day society.

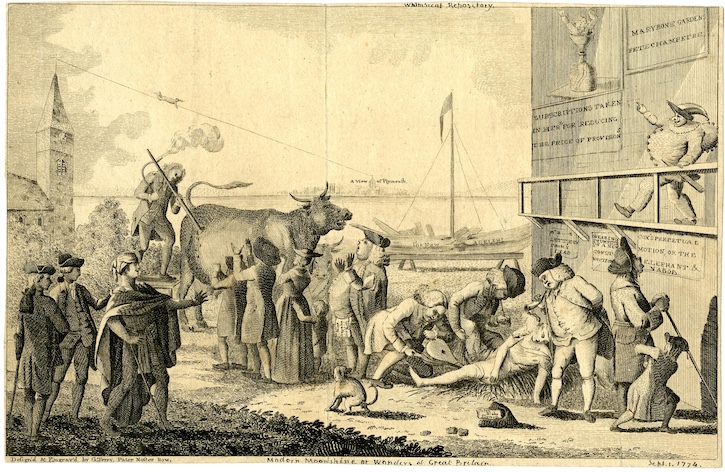

A more popular version of this satirical ventriloquism is found in Garnett Terry's print in which Banks and Solander, drawn from the image shown above, are seen leading an astonished Mai around Britain, where he witnesses some of the follies of the age.

Modern moonshine, or the wonders of Great Britain

1774, engraving by Garnett Terry (1744/1746–1817)

In 1775, Banks introduced Mai to William Hunter. With his brother, John, the Hunters were the most celebrated anatomists and surgeons of the day. Both were fascinated by Cook's voyages and collected objects that were brought back from them.

John Hunter (1728–1793)

1786, 1787 & 1789

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

John Hunter was particularly interested in collecting human remains, including skulls, to add to his collection. This material fed his interest in theories of racial difference. In the same year that he wrote his essay 'Inaugural Disputation on the Varieties of Man' (1775), he also commissioned a portrait of Mai, whom he likely met in person.

A few years later, in 1783, John Hunter opened his residence in Leicester Square to the public. It had an anatomy school and a museum displaying his collection of human and animal anatomical preparations. You can find out more about the Hunterian Museum on Bloomberg Connects. Mai's portrait was hung on the balcony rail dividing the upper and lower register of the museum.

Numbered 241, according to its placed on the rail, the painting was situated as the first in a line of portraits of other foreign visitors: 242, Portrait of a Chinese Mandarin, thought to be the Chinese modeller, Tan-Che-Qua or Chitqua attributed to William Mortimer; 243 Portrait of Caubvick, an Inuit woman from Labrador, by an unknown artist; 244 Portrait of a Malay Woman, by Robert Home; and 245 and 246, a pair of portraits by William Hodges, each entitled Portrait of a Cherokee Indian.

Portrait of a Chinese Mandarin

1770/1771

John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779) (attributed to)

Portrait of a Malay Woman

1770–1788

Robert Home (1752–1834)

It is shocking today, perhaps, to think of the manner in which, in Hunter's museum, Mai's portrait was displayed as a depiction of a racial type, a painted specimen surrounded by human specimens, including the skulls of other people from Oceania. The Hunterian Museum's guide on Bloomberg Connects examines Hunter's ideas around race in more detail.

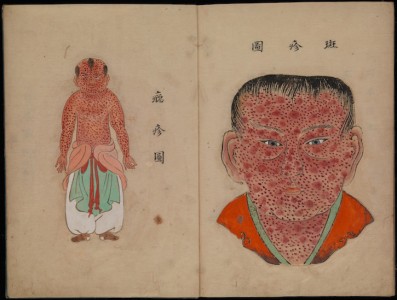

It's fitting that Reynolds's portrait of Mai is currently on tour given that, during his stay in England, Mai travelled widely around the country. He went to a horse race in Leicester. He visited the house of the medical doctor and politician Baron Thomas Dimsdale in Hertford, where he was inoculated from smallpox. He swam off the coast of Scarborough on a trip from York to Mulgrave Castle in Lythe. He stayed at the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich's estate at Hinchingbrooke and at Banks's estate in Lincolnshire.

In William Parry's group portrait, which features Mai alongside Banks and Solander, it is unclear whether the scene to the right is a painted landscape or a view out of a window. The evocation of a distant horizon indicates the movements of the Raiatean through different physical spaces.

That mobility, however, is contrasted by the static, almost passive way in which he is presented, the object of scholarly fascination for the other two men.

Joshua Reynolds' 'Portrait of Omai' at the National Portrait Gallery, London

The Bloomberg Connects guide allows access to hundreds of museums worldwide

He strikes a more active, heroic figure in Reynolds's painting. Reflecting on the many images that were made of Mai during his stay in England, one thing is certain: his status in this country was much less clear and coherent than the figure in that great painting would suggest.

Ben Pollitt, art historian

'Journeys with Mai' is at Cartwright Hall, Bradford, until 17th August 2025. The portrait will travel to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (17th October 2025 – 8th February 2026) and the Box, Plymouth (14th February – 14th June 2026)

The Bloomberg Connects app is free to download from the App Store or Google Play. Download Bloomberg Connects today.

This content was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies

Further reading

Frances Burney, The Early Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney, Vol. II: 1774–1777, Lars E. Troide (ed.), Oxford, 1990

Richard Michael Connaughton, Omai: The Prince Who Never Was, Timewell Press, 2005

Kate Fullagar, The Warrior, the Voyage, and the Artist: Three Lives in an Age of Empire, Yale University Press, 2021

Kate Fullagar, The Savage Visit: New World People and Popular Imperial Culture in Britain, University of California Press, 2012

Jocelyn Hackworth-Jones, 'Mai/Omai in London and the South Pacific: Performativity, Cultural Entanglement, and Indigenous Appropriation' in Joanna Sofaer (ed.), Material Identities, Oxford, 2007

Eric H. McCormick, Omai: Pacific Envoy, Auckland University Press, 1977

Nicholas Penny (ed.), Reynolds, Royal Academy of Arts, 1986

Bernard Smith, 'European Vision and the South Seas' in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 13: 1/2, 1950

Caroline Turner, 'Images of Mai' in Cook & Omai: The Cult of the South Seas, Michelle Hetherington et al., National Library of Australia, 2001

Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815, Cambridge University Press, 1991