Albert Goodwin (1845–1932) was a prolific British watercolourist and landscape artist. During his lifetime, he was feted as a successor to J. M. W. Turner.

Goodwin produced over 800 works, many of which were exhibited in high-profile solo exhibitions and galleries. While his paintings and drawings began entering public collections during his lifetime, interest in them seemed to wane shortly afterwards. Only a small fraction of his works remain in public collections, notably at Tate and in his hometown art gallery at Maidstone Museums.

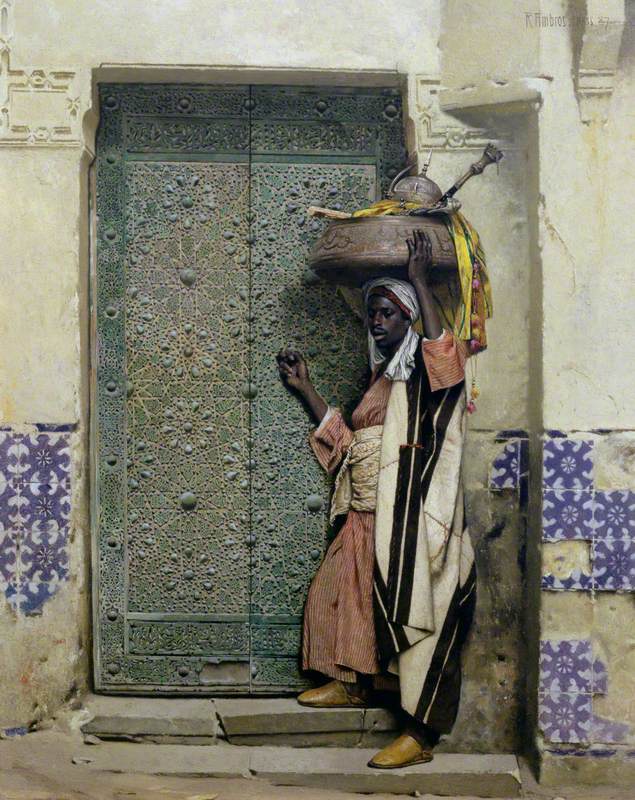

In spite of the many Orientalist fictional landscapes he produced, Goodwin's works are notably absent from discussions and surveys of British Orientalism.

One such fantasy landscape is Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, completed in 1901 and acquired by Tate soon afterwards, having been gifted to the British nation via the Chantrey Bequest, following its purchase by the Royal Academy of Arts for 300 guineas.

Like his other visionary paintings, the canvas is large and luxurious. The scene feels as familiar as it does alien. This might be an exaggerated Cornish coastal scene, albeit with cabbage palms that are too tall, next to coconut palms and other subtropical planting that has settled along the southern British coast as a kind of reciprocal imperialism.

The scene frames the legendary cave in the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. In the tale, this cave stored the goods allegedly stolen by the nameless thieves. The faceless people queue, the line going right around the cliff. They are not just men; among them is at least one veiled woman. Carrying ottomans and vessels, they look more like traders taking wares to market than the villainous and armed marauders of the story. There is no suggestion that the cave is sealed, nor that 'Open, Sesame!' is about to be given voice. The spectator takes on the gaze of Ali Baba, reflecting his occluded position at the story's beginning.

Interpretation of this painting has centred on the popularity of stories from The One Thousand and One Nights, or its Anglicised title, The Arabian Nights, and how they captured the Western imagination with tales of Orientalist magic and adventure. Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves became an especially well-told story, particularly the emblematic incantation of the words 'Open, Sesame!'.

Tales from The One Thousand and One Nights appear in Persian and Arabic texts from the Middle Ages. These stories were retold and influenced differently in various cultural traditions until 1704, when Antoine Galland made the first printed edition in French for a Western European audience. These translations were closely based on the stories told to Galland by travelling Christian Syrian storyteller Hanna Diyab; some of the stories, such as Ali Baba, may even have been Galland or Diyab's own creations, as they do not appear in Persian and Arabic revised editions of the tales.

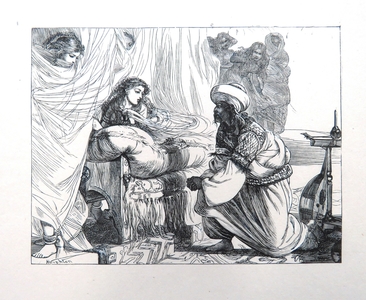

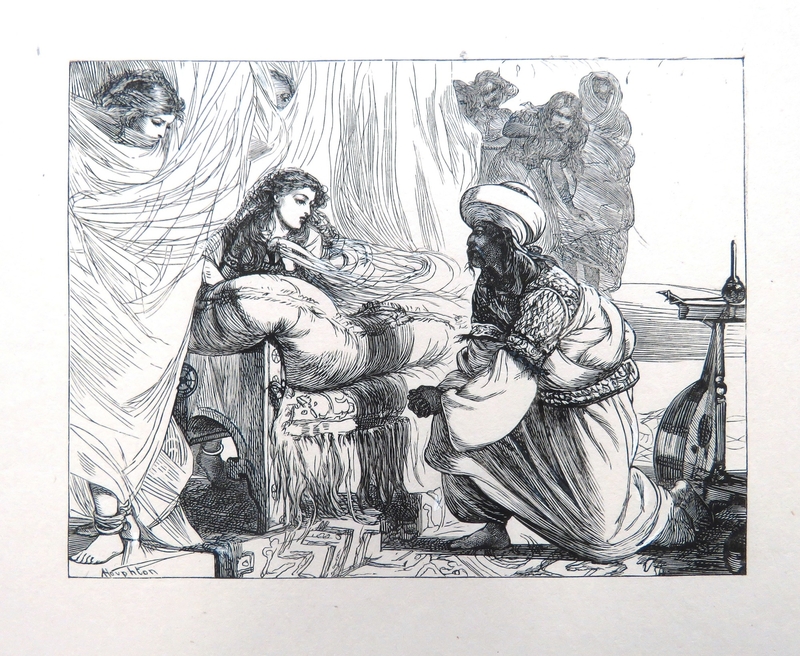

Illustration to 'The Arabian Nights' Entertainments'

c.1865

Dalziel Brothers (active 1830–c.1890) and Arthur Boyd Houghton (1836–1875)

Galland's translations immediately spawned several others, including anonymous editions in English, and are widely regarded as codifying and 'Orientalising' what were already (mostly) popular folk tales from China, India, Russia and Persia. Indeed, the case of Ali Baba – and other tales that seem only to emerge from the Galland-Diyab era – suggests it was itself an Orientalisation intended for an eager and receptive Western audience.

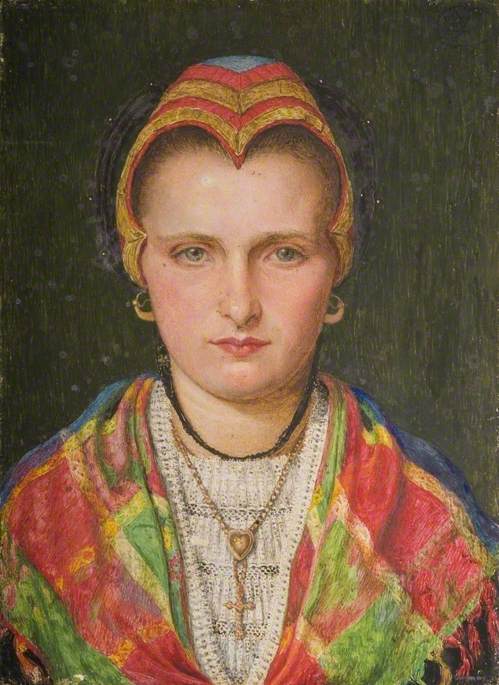

Princess Parizade

published 1864

Dalziel Brothers (active 1830–c.1890) and Arthur Boyd Houghton (1836–1875)

Goodwin would not have been short of inspiration when conceiving of his allegory on these tales. In 1865, the Dalziel Brothers published a lavish Illustrated Arabian Nights' Entertainments. Then, Orientalist Richard Burton published what he considered the most authentic interpretation in the English language from 1885 to 1888. In 1888, Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov completed his blockbuster symphonic suite Sheherazade (the name of the main narrator-protagonist in many of the tales), further evidence that stories and characters like Ali Baba, Sinbad and Aladdin were gaining significant popularity across British society, entertaining both children and adults.

Most people would not be able to recount the main features of the Ali Baba story, even if they were brought up with it through books and cartoons. Listen to the story and you will learn that the main hero is not Ali Baba but Morgiana, his enslaved servant, and the moral of the tale relates to the consequences of brotherly deception: the thieves themselves are cardboard villains. It is Morgiana who saves Ali Baba from his brother and his thieving gang by tricking them and boiling them alive in hot oil. However, this part of the story is not nearly as well-known as the cave scene and the grain-invoking magic formula 'Open, Sesame!'. Indeed, Tate's caption assumes this is the moment we are witnessing in Goodwin's story-scene. But are we?

In Diyab-Galland's edition of the story, in French, the line goes 'Sésame, ouvre-toi!' but in Richard Burton's version, he used the line 'Open, O Simsim' – 'simsim' being the Arabic word for the sesame seed, and in Burton's mind, much more 'authentic'. In Arabic, the phrase is transliterated as 'Iftaḥ yā simsim' and in Gujarati and Urdu tellings as 'khul ja sim sim', where 'sim sim' is just a nonsense word rather than meaning sesame seed; though in some versions when Ali Baba's brother forgets the magic phrase and ends up stuck in the cave, he tries in vain to invoke other grains, such as barley.

While debates continue around the phrase's meaning, including possible origins in a Germanic folk tale from the Brothers Grimm about a treasure-bearing living mountain called Semsi, none seem especially relevant to Goodwin's representation. If Goodwin did harvest his vision of the cave scene from a Burton translation, then the line 'Open, Sesame!' has even less place in subsequent interpretations of the painting.

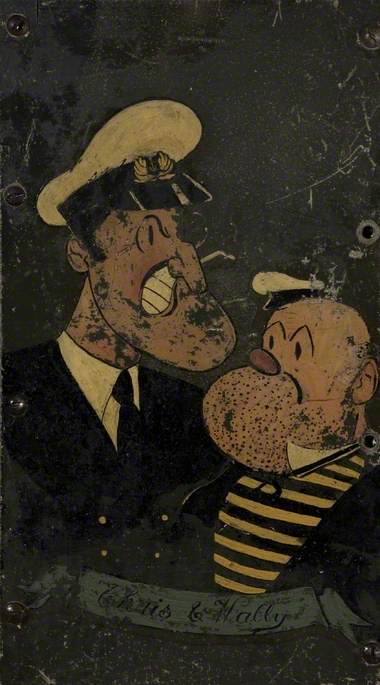

In a peculiar twist, the fixation on this phrase since the mid-twentieth century may have derived from the writers of the Popeye cartoons. In 1937, Fleischer Studios produced a surreal parody called Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba's Forty Thieves for Paramount Pictures. The hero Popeye takes on the evil Abu Hassan (a disguised Bluto, his nemesis) and, to aid his final triumph, reaches for his trusty can of spinach and commands, 'Open, says me!'. This cult line endured, frequently misquoted as, 'Open, Sesame'. The same studios also produced Sinbad and Aladdin-inspired cartoons, but these were created well after Goodwin's time.

Literary scholar Arafat Razzaque emphasises the critical importance of analysing the reception of the stories from a globalised point of view that is fully inclusive of Western orientalism: 'In response to Western discourses of the Other today, resorting to ethnic nationalism of essentialist assumptions about cultural identity would be to miss the moral of this story … it would be a dismissal of the non-Western world's own rich traditions of cosmopolitanism, as exemplified by the real and imaginative threads connecting the Middle East and East Asia in the One Thousand and One Nights.'

However, the globalised view cannot be taken simply in opposition to the kind of othering endemic in interpretations of Western art and literature inspired by real and imagined versions of 'the East'. If Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves was indeed an Orientalist invention by Galland or Diyab, it is impossible not to see the story, and its many visual representations, as anything other than a fantasy enmeshment that is hard to geo-culturally locate.

Goodwin's fantasy landscapes were predominantly painted between 1880 and 1920 and were inspired by Bible stories, Shakespeare, classical Greek mythology, as well as fashionable literature and folk tales. Many of these paintings are epic in scale and vividness compared to his other, more subtle, smaller and intimate topographical watercolours and drawings.

Scene from 'The Tempest'

(from the play by William Shakespeare) 1920

Albert Goodwin (1845–1932)

Albert Goodwin's motivations and influences as a career artist provide useful context to better understand why and how he created paintings like Ali Baba.

Goodwin took advantage of the privilege of having well-connected patrons and champions such as John Ruskin, who introduced him to the importance of travel to diversify and claim his expertise in this genre of landscape painting. Consequently, he became an inveterate traveller, often financially supported by a patron. He toured domestically across Britain and internationally, including in Italy, Egypt, India, the West Indies, North America and New Zealand.

Goodwin's choice to visualise fictional exotica that was fashionable and accessible at the time – such as the Arabian Nights – created a healthy market for his work. A glowing review in The Athenaeum of 1900 described the artist as the 'most accomplished practitioner amongst us' of allegorical landscapes. To the reviewer, Goodwin had a rare ability to combine painting the natural environment into his fantastical scenes to fully immerse the spectator.

Goodwin's motivation for producing art in this genre, and his prolificacy in general, was at least in part 'driven by religious belief and moral responsibility to express his talent and provide for his family.' Ella Martignetti describes his body of visionary landscapes as 'potboilers'.

Touring enabled Goodwin to collect a broad mental and pictorial library of scenes, light, colour, vegetation and topography; he drew on these extensively as material for his fantasy landscapes, creating palimpsests of magical realism. Goodwin commented in his diary: 'nature has an endless storehouse to draw upon and to draw from.' Working this way inspired Goodwin to keep producing: 'To me this method of work is one of the happy things of the art that I practise, for I get the realisation of a place twice over, and often the memory makes the scene a better one than the first experience.'

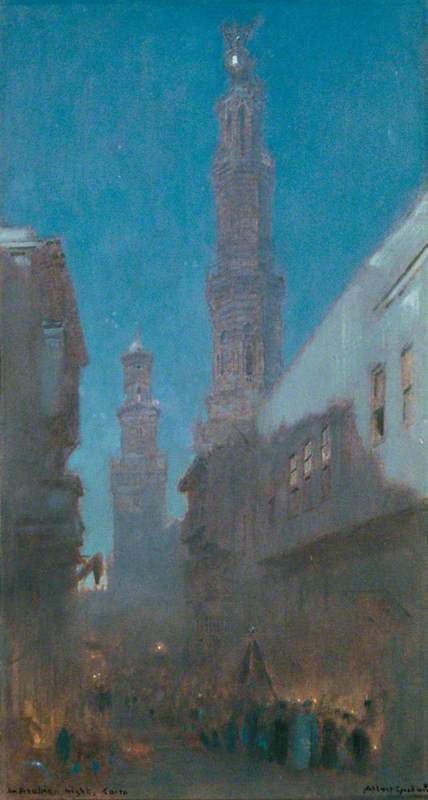

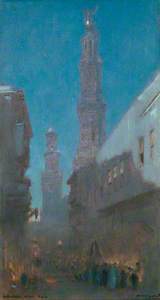

The Mosque of the Citadel, Cairo

1909

Albert Goodwin (1845–1932)

In January 1909, Goodwin arrived at Port Saïd and travelled to Cairo. He spent several days sketching from the Mohattan Hills: 'an old subject of mine, but one that might be well be done again and again.' Evidently, this was not his first visit.

One such destination was the thirteenth-century necropolis centred around the impressive mausolea and mosque of the Abbasid Caliphs. The site had already become a must-see for the travelling artists and architects of the nineteenth century. In his watercolour Tombs of the Caliphs, Cairo, completed in 1898 (private collection), a queue of indistinct people depicted from a distance closely resembles the queue of people at the cave in Ali Baba. This same queue appears in some of his other works.

The scene-setting for Goodwin's visionary explorations was born from the awe the artist had for the natural world, whether it was in Cornwall, Guyana or Italy: 'There is to me a charm in the so-called imagination picture, which the mere portrait of a place does not contain. One gets free play for whatever one has of the inventive faculty, and you are not tied down to hard facts.' After all, the purpose of the Orientalist fantasy was to transport the British viewer somewhere else.

The Goodwin family were mainly based in Ilfracombe, north Devon, while he travelled around the UK and beyond. Around the time he completed Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves in 1901, he was living with a friend, lepidopterist and statistician Dr George Blundell Longstaff, at Twitchen House in Mortenhoe, Devon. Both the north Devon and Cornish coasts were familiar muses for Goodwin, and conceivably the beach cove backdrop to his Ali Baba epic landscape could even have been Mortehoe or Ilfracombe.

Longstaff was another patron of Goodwin. In 1895, Longstaff sponsored his travels to India, and it was perhaps in preparation for this trip that Goodwin familiarised himself with tales that came from 'the East'.

Blue Water in Mounts Bay, Cornwall

1881

Albert Goodwin (1845–1932)

By the turn of the twentieth century, the 'resortification' of many Devon and Cornish seaside villages and hamlets was in full swing and part of this effort was to make these places look like they were abroad. The graphic depiction of these holiday paradises in tourist posters considerably enhanced this effect: they show subtropical plants against a backdrop of turquoise and ultramarine coves and harbours, rocky outcrops and wrecked boats.

View on the Lyn near Watersmeet, North Devon

1881

Albert Goodwin (1845–1932)

Through his visionary landscapes, Goodwin brought Sinbad to the Lyn estuary and Ali Baba to Mortenhoe. While Goodwin's Orientalism is both comfortable and mundane, his domesticity is exotic, inverting the paradigm and inviting us to reconsider how, what and who did the Orientalising.

Goodwin's allegorical landscapes, such as Tate's Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, ought to have a more prominent role in the critique of Orientalism in British late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art. Just like Galland and Diyab may have created the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves from both European and Syrian storytelling traditions, Goodwin was also smudging perceived boundaries between the imagined and real. Open, says me.

Tehmina Goskar, curator and historian

Thank you to Pernille Richards and Mike Howard at Maidstone Museum and Art Gallery for access to relevant excerpts from Albert Goodwin's posthumously published diary. Thank you to Khorshed Bhote for translating versions of 'Open, Sesame' in Gujarati and Urdu, and Dadabhoy Bhote for alerting me to the classic Popeye line, 'Open, says me!'

This content was published as part of the Transforming Collections project

Further reading

Gerald M. Ackerman, Les Orientalistes de l'Ecole Britannique, ACR Edition, 2010

Haythem Bastawy, 'Translations of A Thousand and One Nights', Leeds Centre for Victorian Studies, 2015

Chris Beetles Gallery, 'Albert Frederick Goodwin, RWS RWA (1845–1932)'

Chris Beetles Gallery, 'In Search of Sun and Shadow – The Art of Albert Goodwin RWS', 2019

Chris Beetles Gallery, 'Albert Goodwin RWS (1845–1932) – The John & Mary Goodyear Collection', 2022

Albert Goodwin, The Diary of Albert Goodwin RWS, 1893–1927, privately published, 1934

Ella Martignetti, 'Albert Goodwin: Maidstone's visionary landscape artist', Maidstone Museum, 2020

Arafat A. Razzaque, 'Who was the "real" Aladdin? From Chinese to Arab in 300 years', Ajam Media Collective, 2017

Arafat A. Razzaque, 'Who "wrote" Aladdin? The Forgotten Syrian Storyteller', Ajam Media Collective, 2017

Nicholas Tromans (ed.), Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting, Yale University Press/Tate, 2008

Scott Wilcox and Christopher Newall, Victorian Landscape Watercolors, Hudson Hills Press, 1992