It's nighttime in Corinth, Greece, sometime around 600 BC. The sky is as dark as olives, and a young woman called Kora of Sicyon is heartbroken. Her lover, a young man, is about to depart on a long journey, and she doesn't know if she will ever see him again.

The candlelight dances on the walls of the courtyard, her lover's profile wriggling in shadow on the tile. And then Kora gets an idea. With her lover standing still, she sketches around the shadow, imprinting a drawing of his face directly onto the wall. It's the ancient Greek version of a boyband poster on a bedroom wall – the world's first love doodle.

This story, told by Roman historian Pliny the Elder in Natural History (AD 77), was said to mark the birth of life drawing. Artists in the 1700s and 1800s couldn't get enough of it, often titling their romantic interpretations of the story The Origin of Painting.

The Origin of Painting

(The Maid of Corinth) 1775

David Allan (1744–1796)

Did this tender moment really happen? We'll probably never know. But what the tale of Kora shows us is a truth universally acknowledged: no one makes a better muse than a lover.

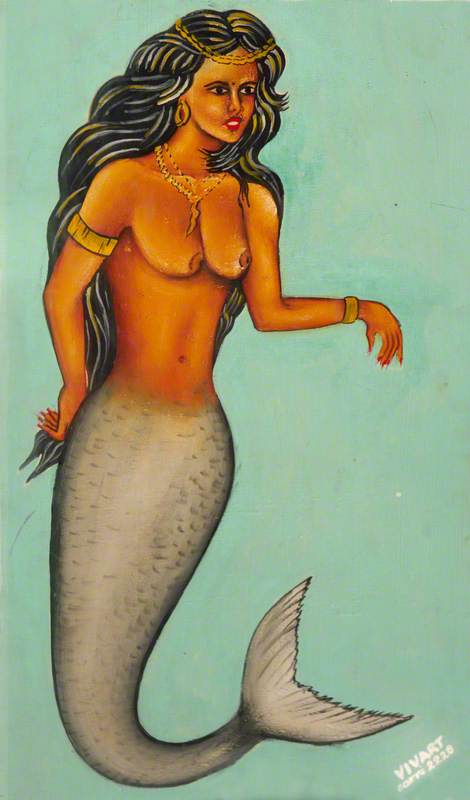

Artists have worshipped muses in bronze, marble, pencil and pastel – but if you really want to peek inside some of art history's most intense, private longings, look to the sapphic sketchbook.

For sapphic artists throughout history, sketchbooks have been safe places to explore intimacy, identity, and longing in ways public artworks couldn't. 'Sapphic' – another word for lesbian – comes from the name of the ancient poet Sappho from the island of Lesbos. Women artists who desired women used drawings as ways to act out fantasies, capture private moments, or depict themselves in new, queer ways, outside of the male gaze. They often lingered with their pencil in places their eyes could not.

Take Scottish artist Ethel Walker, born in 1861 in Edinburgh. Openly lesbian at a time when secrecy was the name of the game, Walker is best known for her portraits of women from anonymous 'fish girls' to famous artists like Barbara Hepworth and Vanessa Bell.

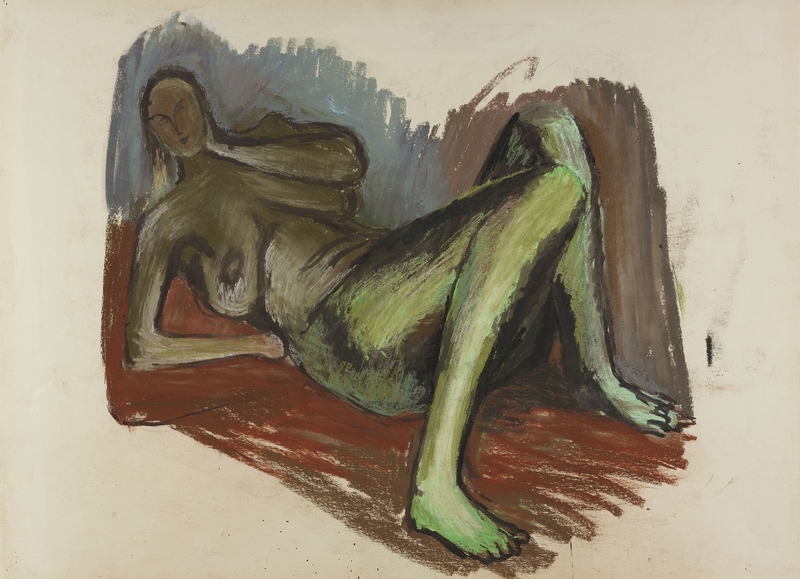

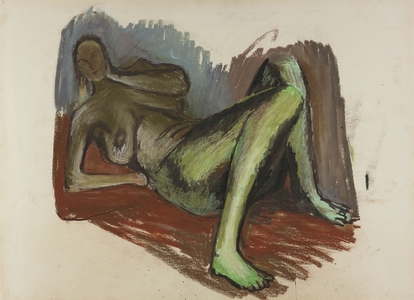

It's in her nude drawings, though, where the lovestruck and sexually curious Walker comes out to play. In one undated work, Reclining Female Nude, a butter-blonde woman lies against a green pillow, a soft smile playing on her lips. Her body is long, sharp, sure of itself. You get the feeling that if you touched her hip, you might cut yourself. She's no passive sex object.

Could this be the model Walker once described in a letter as having 'such lovely naturally curling golden hair [...] like a Botticelli angel, with beautiful features and expression'?

Maybe. What's clear is that Walker's gaze is full of curiosity, not just for the body, but for the person inside it. You half expect the woman to open her eyes and start telling you about her dreams.

Another work by Walker shows a woman teasingly pulling aside a gauzy, pink strip of cloth – not unlike the opening scene of a burlesque show (Sabrina Carpenter, anyone?)

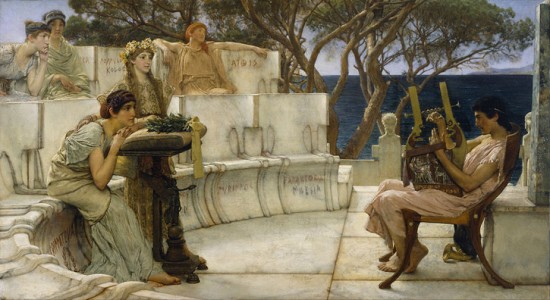

Walker made many paintings titled Decoration, and we don't know exactly which one this was made in preparation for. One of Walker's largest and most overtly homoerotic paintings is Decoration: The Excursion of Nausicaa (1920).

Inspired by The Odyssey, the final painting shows the princess Nausicaa enjoying a beach day with her entourage of ladies fit with picnics, ball games, and olive oil rub-downs. A full-blown sapphic seaside fantasy.

In the preparatory work, Walker has plucked one maiden out of the pack. Face obscured, this model is all round breasts and belly, and come-hither pose; she's not a personality, but a figure of desire. It's a very different energy from the reclining nude: less intimate, more invitation.

This kind of bold, sensual pose appears in other women artists' sketchbooks too – like Elizabeth Raikes's Nude Study, or Dora Carrington's masculine Self Portrait. These are women who take up space.

Carrington's portrait in slacks and a newsboy cap radiates a kind of butch confidence. It should come as no surprise that Carrington once wrote, after meeting a pretty woman at a party, 'I became completely drunk and almost made love to her in public.'

Gwen John, on the other hand, was a more demure woman. She had relationships with both men and women throughout her life, including a one-sided obsession with the poet Vera Oumançoff.

Her many love letters and affectionate paintings? It was all 'intolerably overwhelming' according to Oumançoff. And this wasn't the first time John found herself rebuffed by a woman she desired.

Her brother, fellow artist Augustus John, shared a dramatic story in his autobiography: 'One of my sister's unhappy crossings in love led to a drama. She had a great friend at the Slade, a certain girl student whom I will call Elinor. Elinor had formed a close attachment to an outsider... Gwen decided that this affair must be stopped; so, after failing to persuade her friend to break it off, she announced her ultimatum – surrender or suicide.'

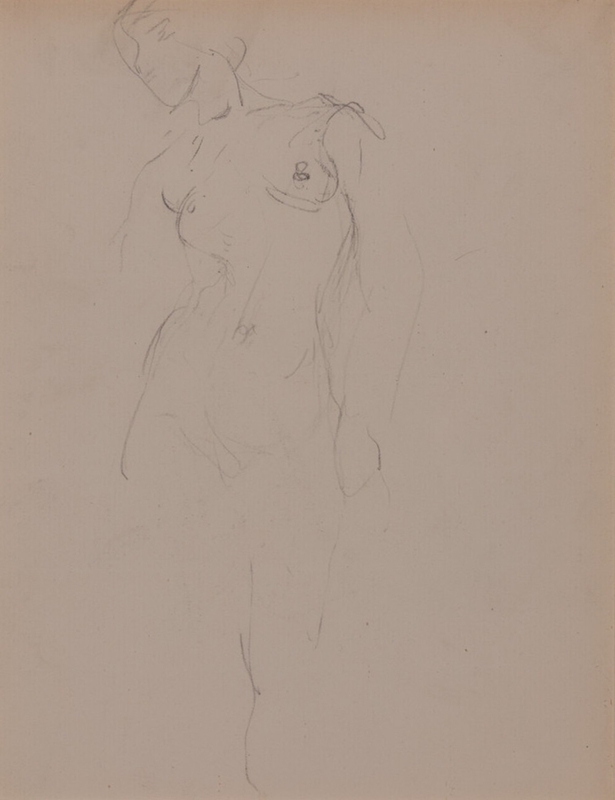

John's fixations found their way onto the page too. As her drawings show, she was both fascinated and unsettled by the female form.

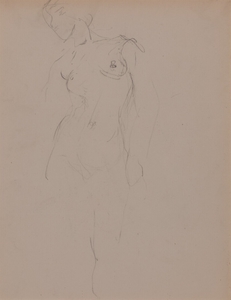

Standing Female Nude (recto); Study of a Seated Woman (verso)

Gwen John (1876–1939)

This full-frontal nude is drawn in soft, delicate pencil lines. The woman's head is turned away from the artist – clearly a gesture John was all too familiar with in real life. Her pencil lingers on the neck, the breasts, the curve of the hips. But below the waist, the lines fade out. Not even a single squiggle of pubic hair.

So why erase her sex? Maybe this drawing was just a quick study for something bigger, or maybe it was something more raw: a sketch drawn in the aftermath of a love affair never quite consummated, leaving the artist full of longing, frustration, and unfinished feeling.

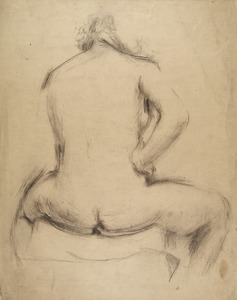

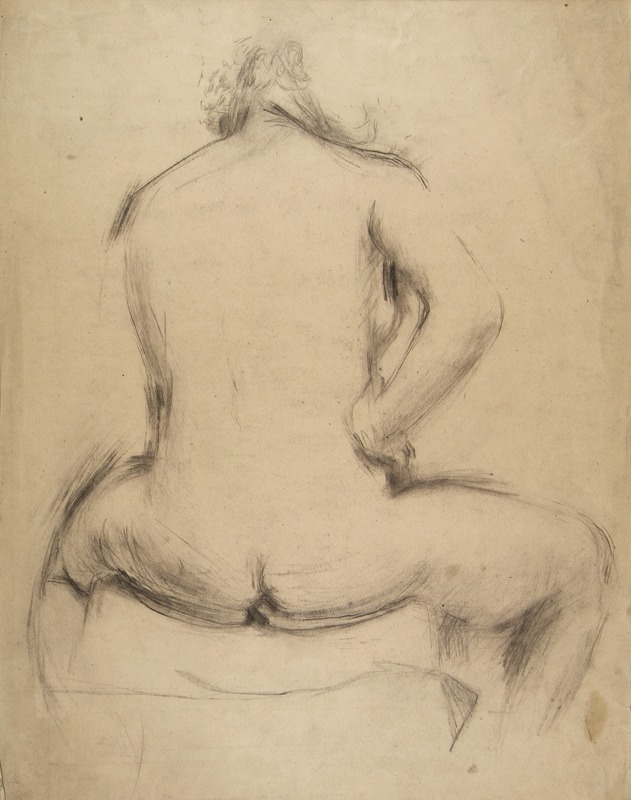

Seated Nude seen from the Back

1948

Joan Kathleen Harding Eardley (1921–1963)

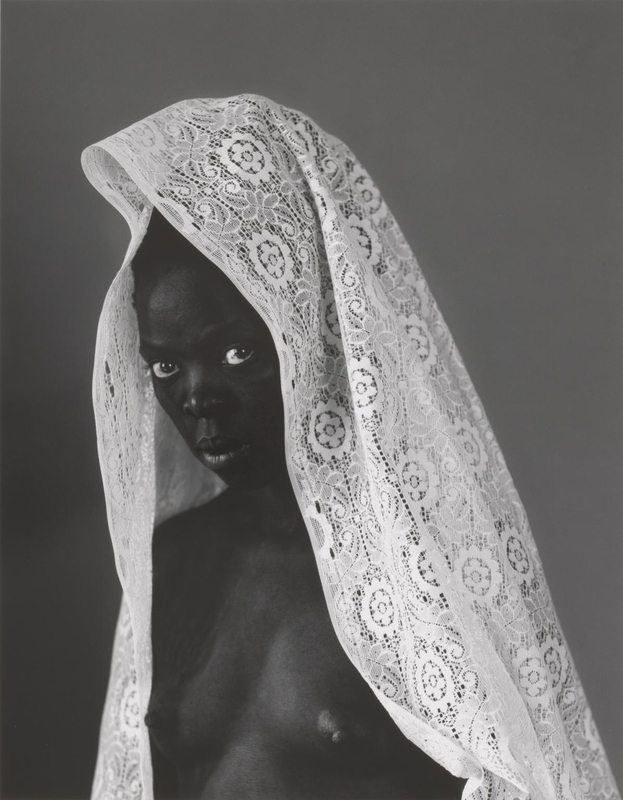

Joan Eardley's drawings keep their secrets, too. Born in Sussex in 1921, she later made Scotland her home and today is celebrated as one of its national treasures. Her paintings capture the wild winds of the Aberdeenshire coast and the tough, scrappy lives of Glasgow's slum children.

But Eardley's drawings hint at something more intimate. In one sketch, a woman sits twisted in a chair, bare from the waist down. After Eardley's death in 1963, it emerged that she had lived quietly as a lesbian, with whispers that some of her closest female friendships may have been romantic.

Could this be a drawing of a lover? The woman's face is turned away, adding to the sense of distance and mimicking Kora of Sicyon's shadowy lover – the original muse traced by candlelight.

It's a vulnerable, private echo of that ancient story. Whether drawn as mementoes of a love affair or testaments to sexual desire, these works show us how the sketchbook became a space for queer women to yearn, to experiment, and to worship the muses they couldn't always name aloud.

Lexi Covalsen, writer and editor

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Emmanuel Cooper, The Sexual Perspective: Homosexuality and Art in the Last 100 Years in the West, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1986

Jennifer Higgie, The Mirror and the Palette : Rebellion, Revolution and Resilience : 500 Years of Women's Self-Portraits, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2022