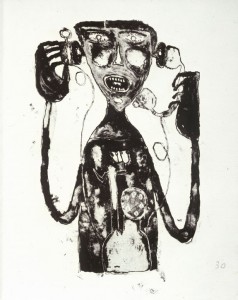

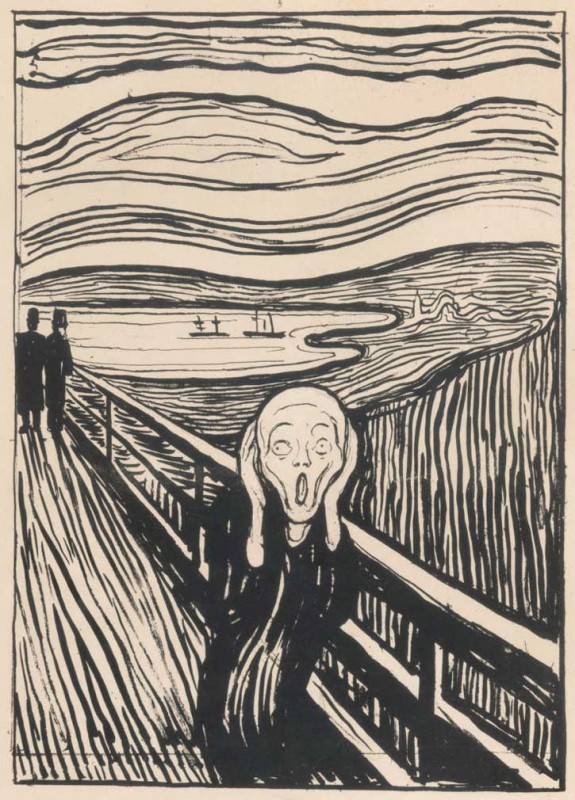

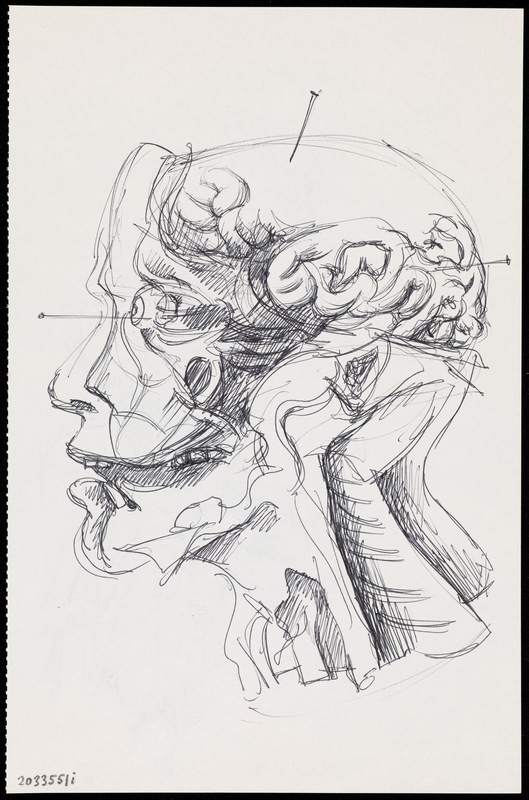

Housed within The Women's Art Collection at Murray Edwards College, Cambridge, is a group of six drawings by the extraordinary British artist Cynthia Pell (1933–1977). Pell's short life was marked by recurring mental illness and long periods of institutionalisation. In the delicacy and expressiveness of her line, we can see the challenges she faced. These drawings were made in moments of solitude, anguish, or insight, in which bodies and faces flicker between presence and dissolution.

Pell's early drawings reveal an artist of remarkable sensitivity and skill, shaped by a privileged upbringing and underlying emotional turmoil. Born in 1933 into a middle-class London family, Pell was raised primarily by a beloved nanny, a source of calm and protection amid familial disputes. From an early age, art was a priority in her education, and her talent was quickly recognised. After winning a national prize, she studied in Bournemouth and later at Camberwell Art College, where she developed her distinctive graphic style.

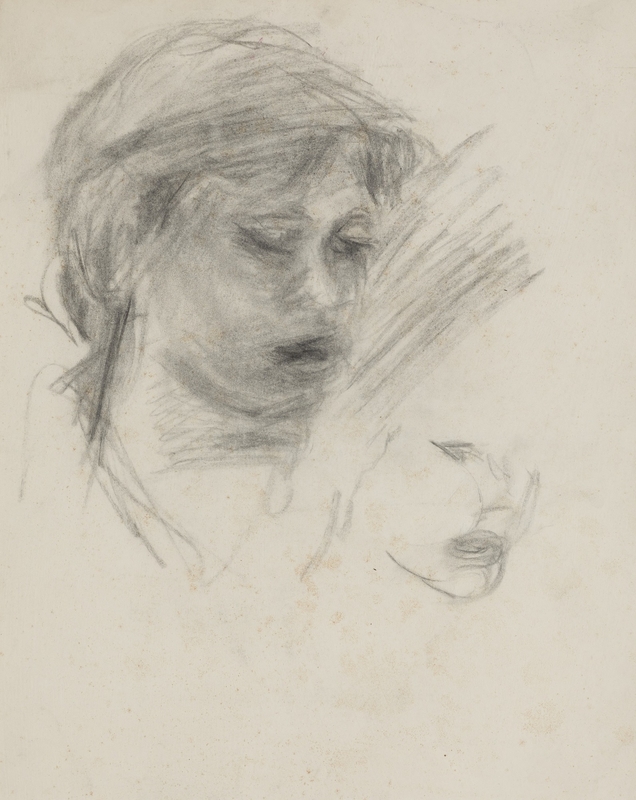

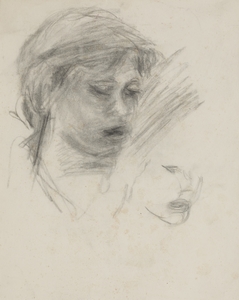

Two charcoal drawings from 1955 – Study of a Girl and Portrait of an Adolescent – capture their young subjects with a quiet, contemplative intensity, as though they have been observed in a moment of unspoken thought. That same year, during a stay in a farmhouse in Provence with her husband, Ron Weldon and fellow artists, Pell produced many drawings of local peasant communities.

As her friend Evelyn Williams recalled, Pell treated her sitters with great warmth, drawing them with honesty: 'Cynthia always seemed deep in thought, but sensitive to others' moods, and always attempting to search out the truth of any situation.' Her early drawings suggest a sensibility focused on the inner lives of others, rooted not in romanticisation, but in careful observation and human connection.

By the late 1950s, signs of psychological fragility had begun to surface in Pell's life. Though deeply intelligent, widely read, and politically engaged, she also became increasingly withdrawn and volatile. Friends and family recall mood swings, extreme weight loss, and a growing dependence on sleeping tablets and stimulants. Her sister particularly remarked on her obsessive interest in Aldous Huxley's book Doors of Perception (1954) in which he reflected on his psychedelic experiments.

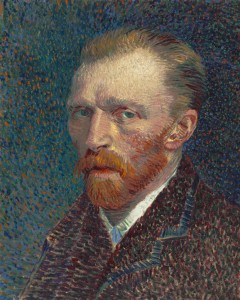

Pell's artistic career culminated in her only solo show in the year 1957 held at the Beaux Arts Gallery in London. The show presented 44 intimate portraits of friends and family, rendered in an emotionally charged expressionist style. Reviewing the exhibition art critic David Thompson praised Pell as 'an interesting and original new talent,' yet the review continues:

'Every face is lit with anxiety and fear, the eyes glittering with fever, the hands clenched in despair. Such visions are usually expressed in the anonymous terms of a generalised humanity rather than in those of identifiable personalities and the way it is particularised in this case makes it the more disturbing... It is sometimes ugly, sometimes overstressed, and hysterical as expressionist painting so easily becomes.'

The portraits were unsettling precisely because her anguish was personal, not abstract. This review foreshadows what was to come, already using pathologising language such as 'hysterical.' After the show, Pell carried many of her unsold works onto the pavement and set them alight – an action generally interpreted as a gesture of despair and uncompromising perfectionism.

In 1961, Pell was first admitted to St Bernard's Hospital in Southall where she remained a patient intermittently throughout the next decade. Negative responses to the treatments she received there (including psychoanalysis and various medications) led to her transfer to Bexley Hospital in 1973.

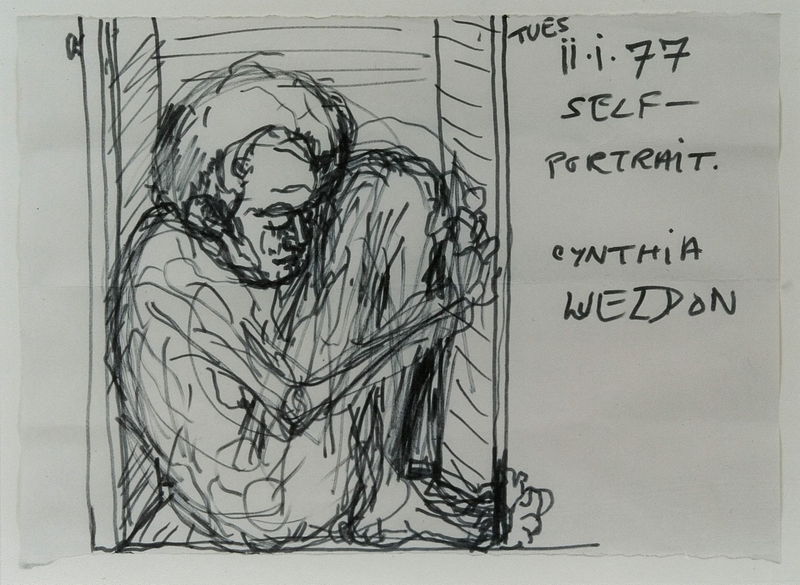

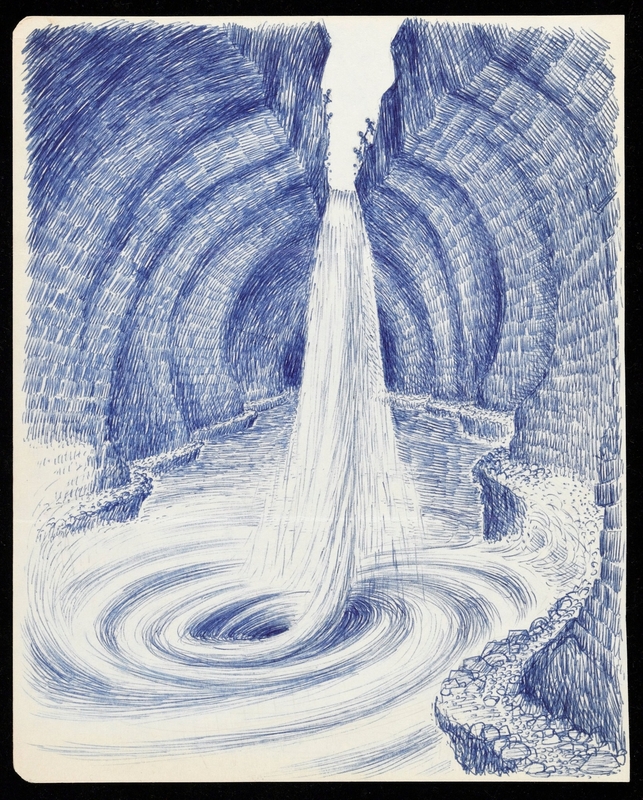

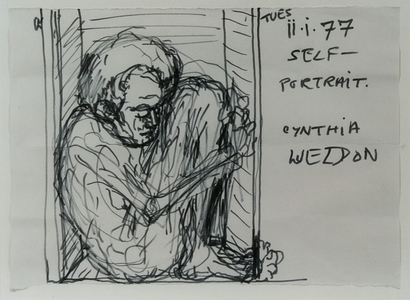

Pell spent the final four years of her life as a patient at Bexley Hospital in Kent. There, she met art therapist Britta von Zweigbergk, who became both a trusted friend and the informal guardian of Pell's artistic legacy. Though often withdrawn during the day, Pell would come alive at night, wandering the hospital corridors and capturing moments of quiet despair, odd humour, or intense solitude in quick, expressive drawings.

Her works from this period carry the immediacy of witness accounts. Zweigbergk recorded in her notebook that after initial disinterest, Pell started gravitating towards the art department: 'Her mood began to lift and she started to draw – often quite feverishly and with great energy she would draw fellow patients, members of staff. I supplied paper pencils, chalk whenever she wanted and she started to come into the department.'

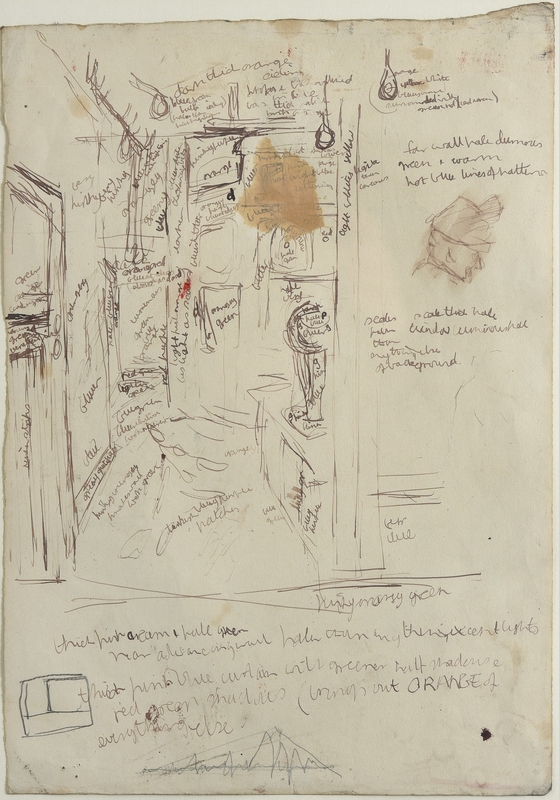

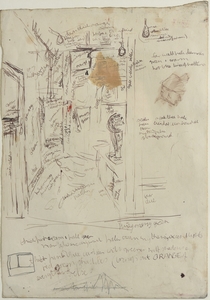

Drawn in biro, crayon, or pencil on scraps of paper, hospital forms or reused packaging, these works were either observational or carried the visual rhythm of someone urgently trying to pin down fleeting thoughts or moods. In pieces like Study for a Room (1976) and Self-Portrait in Cupboard (1977), half-legible notes merge with her subjects, including fellow patients, nurses, herself, or her ward. Yet these are not caricatures or therapeutic exercises: they are complex portraits of real people blending empathy and irony, immediacy and restraint, tracing moments of tension, loneliness, and rare stillness.

In their raw honesty and expressive economy, they remain among the most powerful visual documents of institutional life in postwar Britain. The drawings often include time stamps, her married name, symbols like the Star of David or her patient number, as if asserting identity through repetition and routine. Zweigbergk thought these were 'signs of belonging' – to her family, to her Jewish roots, to the ward, and ultimately to the institution in which she spent a significant part of her life.

Pell's drawing from Bexley Hospital can be placed within a longer, complex history of art-making in psychiatric settings, in which drawing has served as both a form of personal expression and a therapeutic device. Though art therapy was formalised in Britain only from the 1930s onwards, patients had long used drawings as a means to escape, record, or reimagine the confines of institutional life.

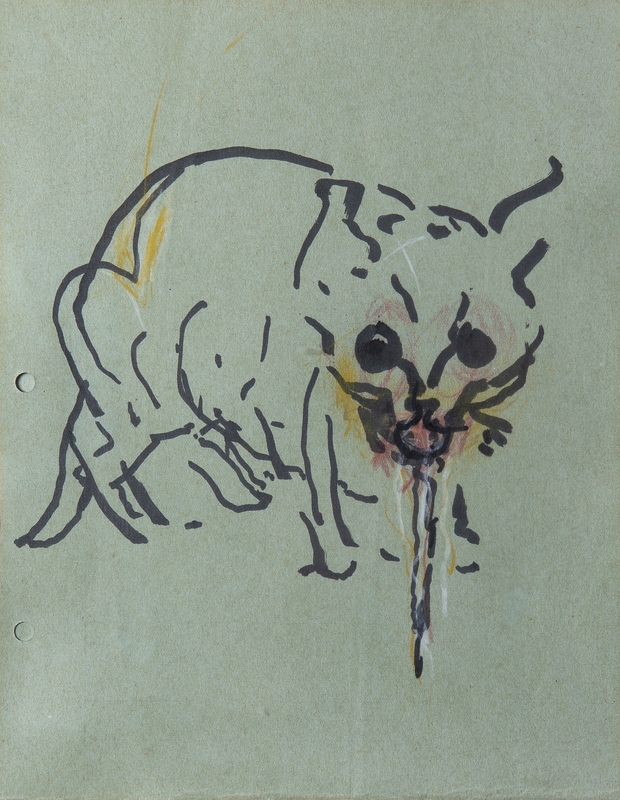

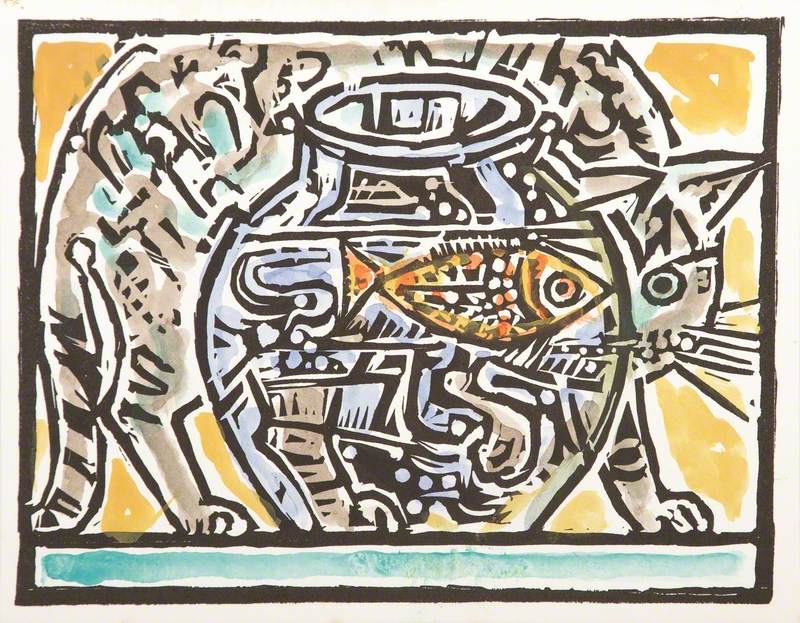

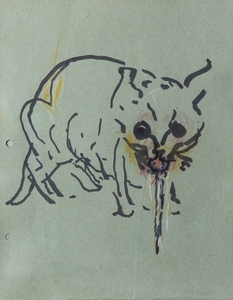

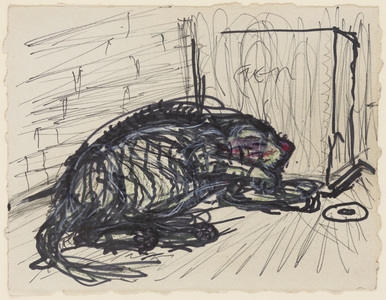

Among the most unsettling works in Pell's later output are her depictions of cats, such as Cat Vomiting (1976) and Cat Sleeping (1976).

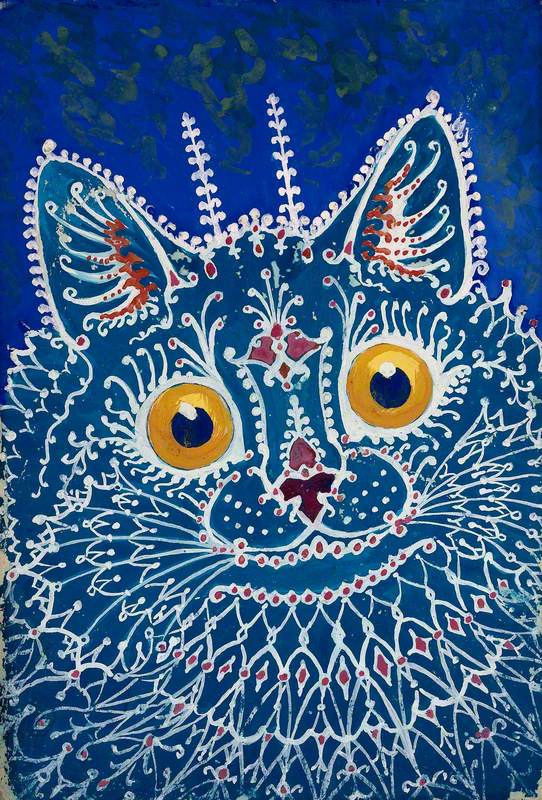

These images recall, perhaps unavoidably, the feline drawings of Louis Wain, another artist associated with long-term psychiatric care.

While Wain's cats grow increasingly animated and fantastical, Pell's cats are far from whimsical or decorative. The cats appear vulnerable, disturbed, and suffering in isolation – observed with the same unsparing empathy that Pell brought to her portraits of fellow patients. The connection between the two artists is not clinical, but symbolic: both artists gravitated toward the feline as a vehicle for something deeply personal and inexpressible, a means of constructing visual worlds within the confines of institutional life.

Pell's legacy as draughtswoman of rare intensity has been safeguarded largely through the dedication of those who knew and admired her. In the years following her death, a small group of friends and supporters, including Zweigbergk, Natalie Dower, Evelyn Williams, Paula Rego, and her sister Barbara Pell, worked to preserve what remained of her work.

Their efforts culminated in two exhibitions and the recovery of almost 200 of Pell's works. Still, most of Pell's drawings were lost, some destroyed by her own hand, others discarded after her death. Yet what survives speaks with urgency and clarity. If modernist drawing has often been framed as conservative, Pell's work reclaims it as something raw, confessional, and fiercely autographic.

Anja Segmüller, art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Natalie Dower et al., Cynthia Pell, 1933–77: Orleans House Gallery, The Cynthia Pell Account, 1999

Susan Hogan, Healing Art: The History of Art Therapy, Jessica Kingsley, 2000

Marsha Meskimmon and Phil Sawdon, Drawing Difference: Connection Between Gender and Drawing, I. B. Tauris & Co., 2016

Louis Wain and Rodney Dale, Catland, Duckworth, 1977

The Women's Art Collection, 'Cynthia Pell'

Britta von Zweigbergk, 'Cynthia Pell (1933–1977): The Artist'