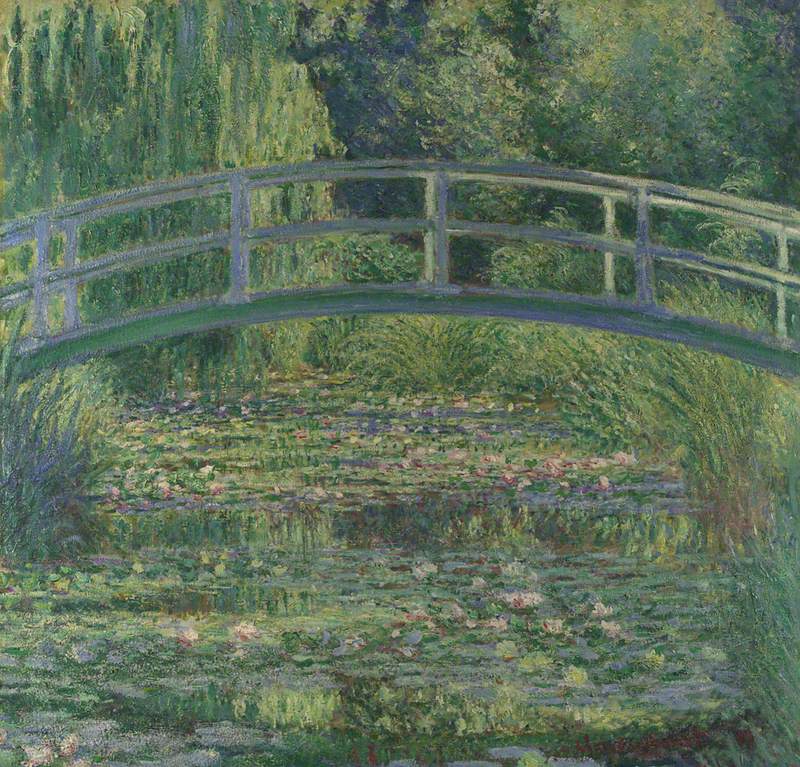

The Impressionists reimagined the way we see the world, and the way we think about making art. With their innovative method of painting, they broke the longstanding mould of art that tried to visually replicate the world. Instead, they tried to paint an 'impression' of it – hence the name. The sense of light, movement, and transience in their paintings came to define modernity itself.

But what about their drawings? Painting was the modus operandi for the Impressionists, but like most artists, they used drawing to work out ideas, prepare compositions and sketch from life. By taking a look at these drawings, we can gain an insight into the different working processes of some of the major Impressionist artists.

Éragny sous la neige (Éragny under snow)

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

The first Impressionist exhibition was held in 1874 by a group of artists who had styled themselves as the Société anonyme des artistes peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc after being repeatedly rejected by the official Academic Salon exhibition. It was a critic who first coined the term 'impressionist' (as an insult), and it stuck.

Camille Pissarro exhibited with the Impressionists from the very beginning. He, like his peers Claude Monet and Berthe Morisot, was particularly fascinated by painting outside, or en plein air. He used loose brushstrokes to work quickly to capture a fleeting scene, rather than working over days or weeks in the studio.

In his pastel drawing Paysannes Assises, made in the 1880s, the way Pissarro made marks on paper is almost more visible than in a painting. Each pastel mark is distinct, showing the traces of the artist's hand as it crossed the paper. The subject matter, described by the title as 'seated peasants', is a classic Impressionist subject: a depiction of the working classes. Pissarro romanticised the life of peasants in the countryside, as their way of life shrank under the shadow of industrialisation and modernity.

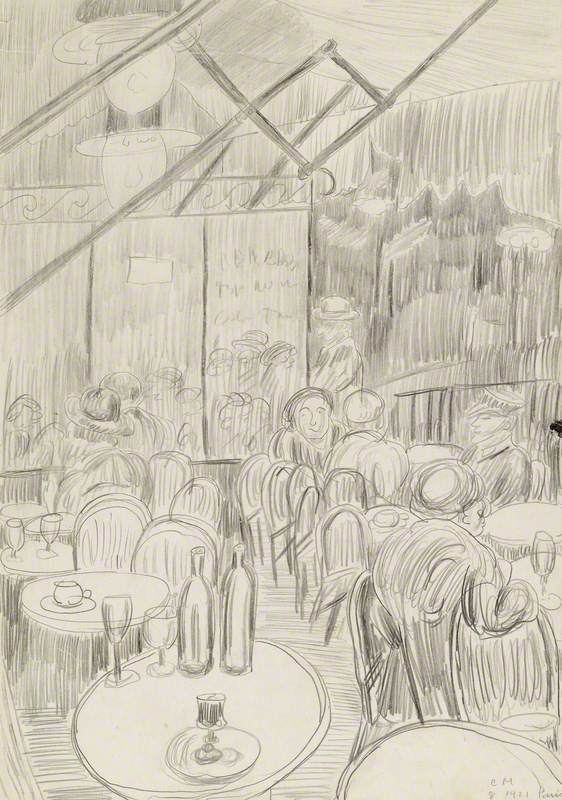

Edgar Degas also exhibited with the Impressionists from the very beginning, but he eschewed working en plein air. He preferred to paint the working classes of Paris. He is particularly well known for his renderings of ballet dancers. To twenty-first-century eyes, these can have the air of money about them, but make no mistake: ballet dancers were barely a step above nightclub dancers in the late nineteenth century. Degas's depictions of them balance his interest in the contortions of their bodies and their assumed sexual availability.

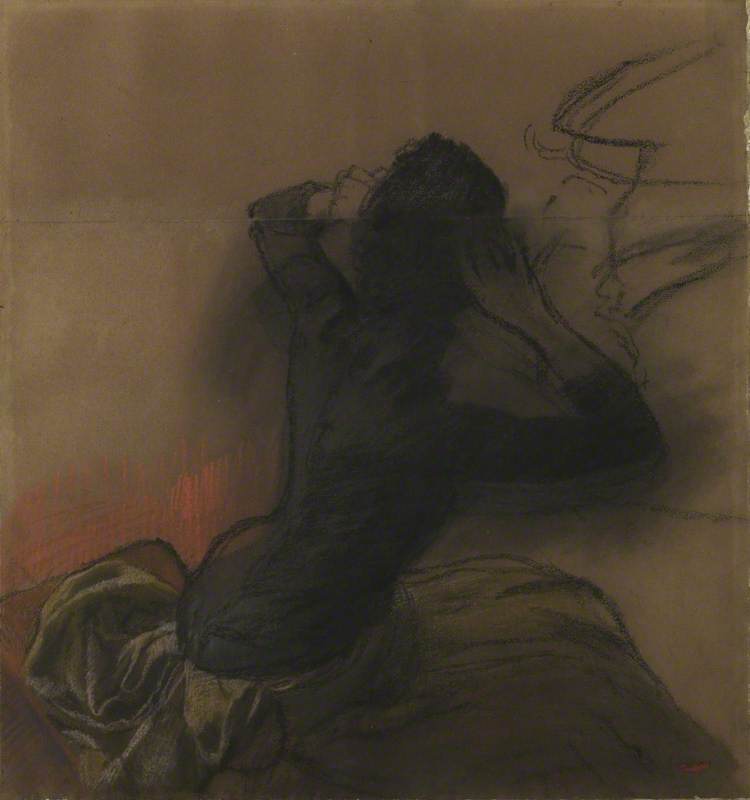

In this drawing, the grid the artist has drawn onto the paper is still visible, giving us clues about how he carefully planned this composition, possibly for use in a larger work later. There is a second arm floating in the bottom right, again pointing to this work's purpose as a tool for study.

Degas was working to capture the particular details of the dancer in motion, and drawing was the quickest, most nimble medium for that purpose. He was unusal amongst the Impressionists for making many preparatory drawings before beginning to paint – many of the other Impressionist artists preferred to paint from life rather than from a drawing.

Woman Adjusting Her Hair

c.1884

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

In this slightly later work from the mid-1880s, Degas's impressionistic markmaking is clear in a different way. Depicting the back of a woman's head, blended charcoal and pastel give the impression that her hair and body is smoking, or lost in mist. She seems to be lifting off, blurry at the edges. There is a sense of ephemerality about her that is communicated through the texture of the medium.

Paul Cézanne also exhibited with the Impressionists, and he received the most criticism in the early days of the movement. His work has since become foundational to the emergence of abstraction in the Western European tradition. This drawing from the late 1880s offers a window into his compositional processes.

Nature morte, objets de toilette

c.1885–1890

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

Probably unfinished, it depicts the outlines of a still life of 'objets de toilette' or toiletries. The objects are all placed in the top left of the composition, with the rest of the paper left blank. They're lightly outlined with washes of colour giving dimension.

It's a remarkable display of economy – with only a few marks, Cézanne has described a ewer and basin and two bottles resting on a surface. His ethos as an artist was economy: he regularly painted still lifes, especially of apples, and was occupied with describing their form in the simplest but most truthful manner possible. His work was a major inspiration to the Cubists.

Berthe Morisot was another of the original Impressionists, and one of three women who exhibited with the group. Her self-portrait depicts herself drawing, sitting on a sofa with her young daughter.

Berthe Morisot Drawing, with Her Daughter (Berthe Morisot dessinant, avec sa fille)

1889

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895)

Morisot was the sister-in-law of the artist Édouard Manet and was unusual in her very successful pursuit of a professional career as an artist after becoming a wife and mother. In this work, she gazes directly out at the viewer, as if she is drawing us, and her daughter peers intently over at her work. By showing herself at work, she confidently claims the role of 'artist'.

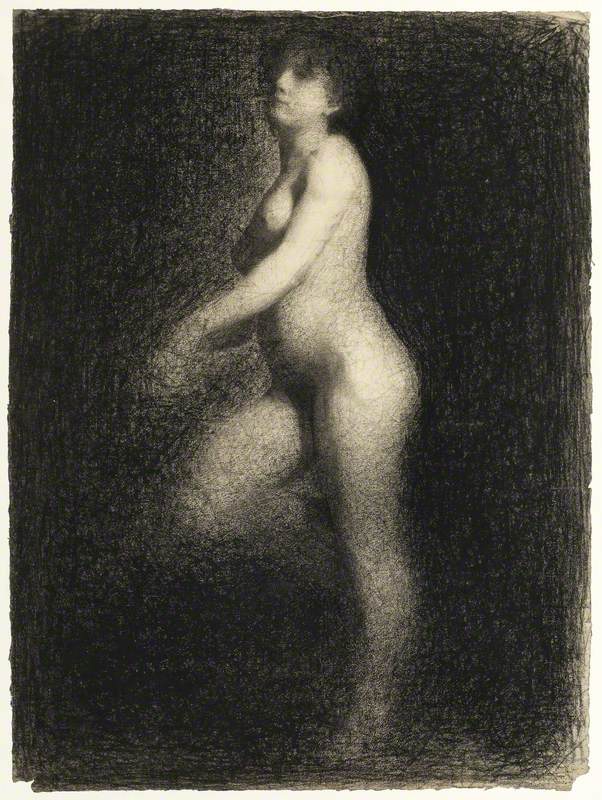

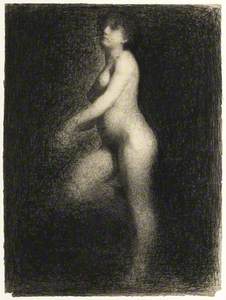

The Impressionists cast a long shadow over modern art. One of their immediate followers was Georges Seurat, who is described as a 'Neo-Impressionist' and developed the pointillist technique. His drawing of a female nude shows the early development of that technique: it is made with thousands of tiny marks or points that blend together to the human eye.

Compare it with Degas's drawing of a woman from behind – they share a sense of the figure dissolving into darkness, but Seurat's style of markmaking is all his own.

The legacy of the Impressionists continues to colour the way we look at art, and the way artists make it. Their radicalism and specific interest in capturing the fleeting moment is as visible in their work on paper as it is in their work on canvas.

Eliza Goodpasture, commissioning editor, drawings

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation.