Reginald Pole stands out in Tudor history as the man who refused to bend to royal will. A devout scholar, a royal by birth, and eventually a cardinal of the Catholic Church, Pole's resistance to Henry VIII's break with Rome marked him as a symbol of religious piety, intellectual defiance, and tragic consequence.

King Henry VIII

(copy after an original of c.1536)

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543) (after)

His portraits depict him as a deeply pious and devout figure, committed to preserving what he saw as the one true faith – Roman Catholicism – no matter the cost. In each likeness, he wears the distinctive red biretta, a square cap marked by three ridges, emblematic of his Catholic identity. The red hue signifies a readiness for sacrifice, even to the point of shedding blood, in defence of the faith.

Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500–1558), Archbishop of Canterbury

17th C

Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547) (follower of)

The portrait above from Lambeth Palace is a copy of a work in The Hermitage by Sebastiano del Piombo, of which there are other copies in Magdalen College, Oxford (below) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500–1558), Commoner (c.1511–1516)

Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547) (follower of)

Pole's story intertwines the personal with the political, pitting loyalty to faith against loyalty to family and country, and it ends with a dramatic return under Mary I of England to lead the country's most determined effort at religious re-Catholicisation.

Mary I of England (1516–1558), and Philip II of Spain (1527–1598)

Lucas de Heere (c.1534–1584) (probably after)

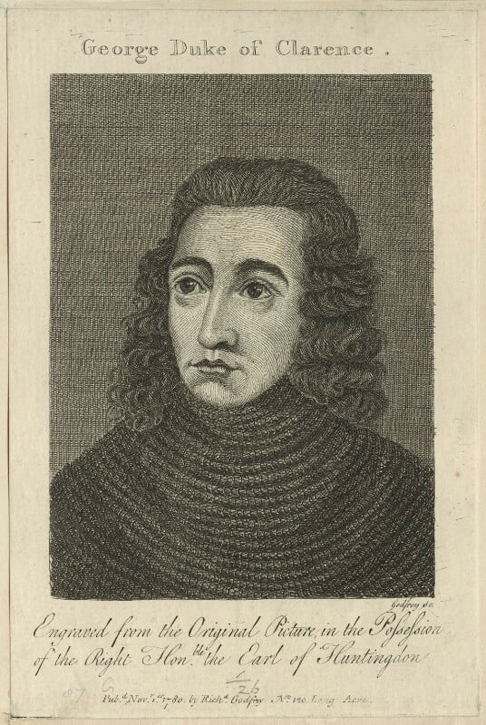

Born in 1500, Reginald Pole was a grandson of George, Duke of Clarence, brother of kings Edward IV and Richard III.

This made him a Plantagenet, a member of the old royal house that had been swept away by the Tudors after the Wars of the Roses. Though the Tudors were firmly in power by the time Pole was born, his lineage, via his mother, Margaret Pole, placed him dangerously close to the throne and made him and his brothers an object of suspicion as well as prestige at court.

Though Pole's piety was evident from a young age, it was, in part, economic circumstances that compelled his mother to steer him toward the ecclesiastical path.

Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500–1558), Archbishop of Canterbury (1556–1558)

Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547) (copy after)

Furthermore, recognising his talent and piety, Henry VIII paid for Pole's education, including a period of study at the University of Padua in Italy. There, Pole immersed himself in theology, classical studies, and the humanist currents of the Renaissance. This education would prove foundational for his later career – and for his moral and religious resistance to Henry's ecclesiastical change.

Pole's education and temperament made him an ideal court theologian – but not an easy political servant. When Henry VIII began to pursue an annulment from Catherine of Aragon and initiate the break with Rome as early as 1527, Pole was caught in a terrible dilemma.

Initially, Henry hoped Pole would support his cause. The king offered him the Archbishopric of York, one of the highest church offices in the land. But Pole refused.

The South West Prospect of the City of York

1735

Samuel Buck (1696–1779) and Nathaniel Buck (d.1759/1774)

As Henry's plans to declare himself Supreme Head of the Church of England became clear, Pole publicly and resolutely opposed him. In 1536, he published his most famous work, Pro Ecclesiasticae Unitatis Defensione, a scathing theological critique of Henry's actions. He condemned the king's break with Rome as heretical and dangerous.

This act was pure treason in Henry's eyes. The rupture was complete.

Pole remained in Italy and Pope Paul III made him a cardinal in 1536 and later put him in charge of diplomatic missions related to England. He never again set foot in his homeland during Henry VIII's lifetime.

Reginaldus Pole (1500–1558), Cardinal Pole

Cristofano dell'Altissimo (c.1525–1605)

Henry's response was brutal. In 1538, Pole's family in England became the target of royal vengeance. His mother, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury (the portrait below was once thought to be of her), was one of the last surviving Plantagenets and had been a close servant to Catherine of Aragon. She was arrested alongside her other sons, Henry and Geoffrey. They were all accused of treason.

Unknown woman, formerly known as Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury

c.1535

unknown artist

Despite little evidence, Margaret was imprisoned for years and eventually executed in 1541 in what was widely seen as an unjust and gruesome killing.

Reginald, writing from abroad, was devastated. His political and religious beliefs and writings had caused his family members to lose their lives. Yet he did not recant.

Pole's life, however, was not one of failure or exile alone. With the accession of Mary I in 1553, the religious and political landscape shifted dramatically. Devout Catholic and daughter of Catherine of Aragon, Mary respected Pole and viewed him as an ally.

She invited him back to England as her chief advisor and spiritual guide in the restoration of Catholicism.

In 1554, Pole returned triumphantly to England after two decades abroad. Appointed papal legate, he oversaw the reconciliation of England with the Roman Church. In 1556, following the death of Archbishop Cranmer, Pole became Archbishop of Canterbury – the very office that had once symbolised Henry's religious independence.

His return marked a symbolic reversal of the Henrician reformation: the exiled theologian who had defied the king was now leading the Church of England back into the Catholic fold.

As Archbishop and advisor to Mary, Pole presided over one of the most intense phases of the English Counter-Reformation. He was a key figure in attempting to reestablish papal authority, revive monastic life, and root out Protestant dissent. The period was also marked by the persecution of Protestants which has long shadowed Mary I's reign and, by extension, Pole's legacy. While these persecutions are now usually put into a broader European context, his name remains tied to the larger attempt to undo the Reformation.

Mary I (1516–1558), Queen of England and Ireland

1554

Hans Eworth (c.1520–after 1578)

Pole's final years were difficult. Though deeply devoted to the restoration of Catholicism, he found himself increasingly isolated politically and ill physically. He fell out of favour with the papacy, especially under Pope Paul IV, who distrusted his conciliatory approach.

On 17th November 1558, Pole died just hours after Queen Mary, bringing an end to the last great Catholic revival of England as the Elizabethan era began.

Reginald Pole (1500–1558), Cardinal and Archbishop of Canterbury

late 16th C

British (English) School

In retrospect, Reginald Pole's legacy is a complex one. He was, above all, a man of conscience – one who placed his faith above personal advancement, even at the cost of exile and family tragedy. His defiance of Henry VIII was not rooted in ambition or personal rivalry but in deep conviction that the unity of the Church must be preserved at all costs.

That he was a Plantagenet only added to the suspicion he aroused at court, but also lent symbolic weight to his return under Mary I, when he briefly embodied the fusion of royal blood, moral authority, and ecclesiastical power.

Reginald Pole (1500–1558), Cardinal and Archbishop of Canterbury (1555–1558)

1585–1596

unknown artist

Pole's tragedy lies in the price he paid – and the ultimate failure of his cause. The England he helped restore to Rome was quickly lost again after his death. But his courage in standing firm against Henry VIII's tyranny and his enduring belief in the spiritual over the temporal, secured his place as one of the most principled figures in Tudor history. He was, truly, a man who defied a king.

Estelle Paranque, historian

This content was funded by The Weiss Gallery