Rachel Jones' 2025 exhibition 'Gated Canyons' at Dulwich Picture Gallery makes her interest in teeth and mouths very clear. Whereas works such as lick your teeth, they so clutch (2021) – which was acquired by Tate only two years after Jones graduated from the RA Schools – hint at her oral interest in jagged brushstrokes and colour gradations, her recent work is more explicit in its imagery.

lick your teeth, they so clutch

2021

Rachel Jones (b.1991)

As she explains in a trailer to accompany her exhibition, these new paintings have an added level of intimacy through her depiction of tongues and gaping or grinning mouths.

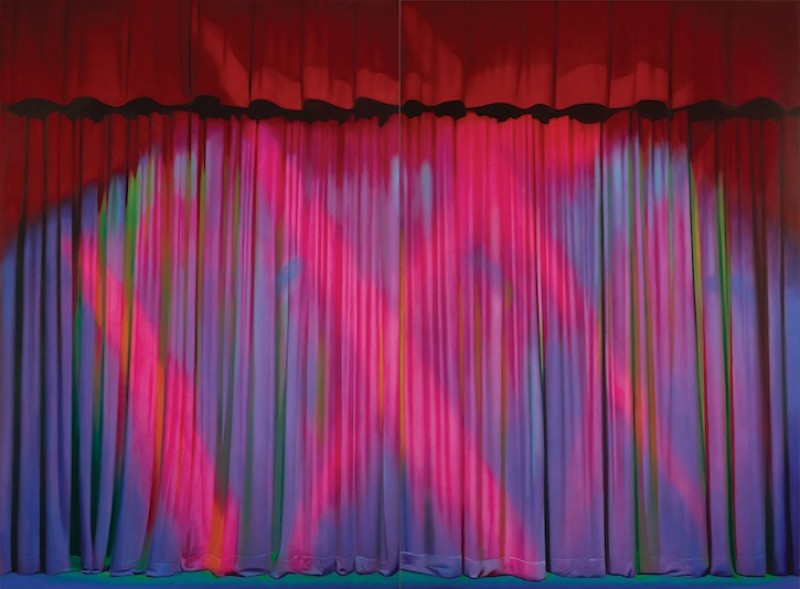

The work below, made using the artist's trademark oil sticks and pastels, in which a big toothy grin appears to run across the canvas, reveals Jones' examination of more extreme emotions for which she draws on the visual history of cartoons. I'm reminded of the work of another young artist, Louise Giovanelli, whose recent work features erotic open mouths as gateways to bodily sensation.

Gated Canyons

2024 by Rachel Jones (b.1991)

There's a fantastic audio guide to the Dulwich exhibition on Bloomberg Connects – hear Jones talk about this work and the idea of the mouth as a form of landscape, as well as the ways in which she pushes the boundaries separating the abstract and figurative.

Jones isn't alone in finding teeth interesting – in fact, the history of art is filled with works about mouths, teeth or dentistry more broadly. For a start, there are many early modern images of infants holding curved pieces of coral designed to sooth their teething gums.

And Dutch Golden Age art features lots of grim images of people undergoing clearly painful dental procedures – in fact, the tooth-puller was a popular topic in genre scenes during this time. As this curation about dental art explains, before dentistry became professionalised in the late eighteenth century, treatment for toothache was confined to the removal of teeth. Be thankful for modern medicine!

Der Zahnbrecher (The Dentist)

early 20th C

Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685) (after)

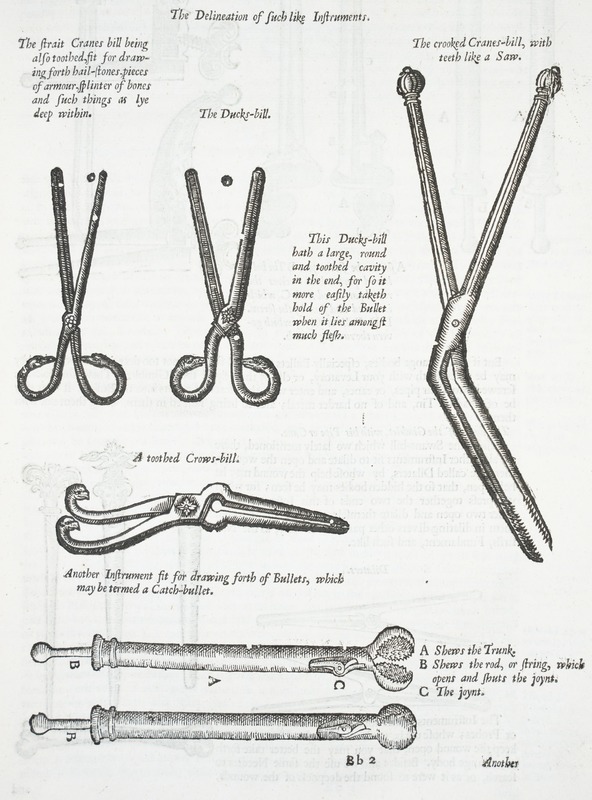

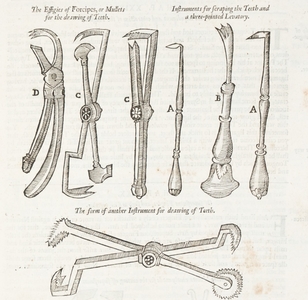

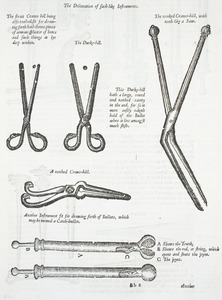

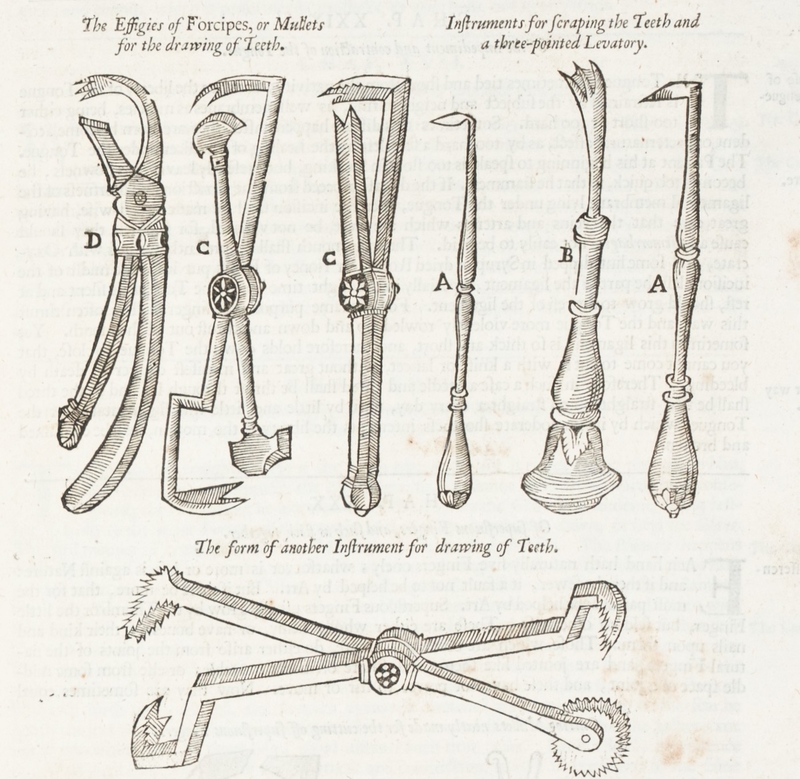

It's unlikely this sixteenth-century illustration of surgical instruments by Ambroise Paré would make you excited about visiting the dentist. The forceps for drawing teeth look particularly nasty.

Surgical Instruments with Teeth

Ambroise Paré (c.1510–1590)

Luckily, those with dental problems can pray to Saint Apollonia, the patron saint of toothache sufferers. A virgin martyr from the second century, she was tortured during an uprising against Christians in Alexandria by having her teeth violently pulled out. Refusing to denounce her Christian faith, she willingly burned herself to death. As this 1506 work by Lucas Cranach the elder shows, Apollonia (on the right) is usually depicted holding a pair of pliers in reference to her own extractions.

Saints Genevieve and Apollonia

1506

Lucas Cranach the elder (1472–1553)

It's rare in Western art history to find many portraits in which the sitter reveals their teeth – and not just because of terrible dentistry. Closed mouths were regarded as more refined, with teeth-baring grins associated with genre paintings depicting the lower classes. That the grinning lute player in this portrait by Frans Hals holds out a wine glass suggests the link between unrefined expressions and merrymaking in the seventeenth century.

In the late eighteenth century, French painter Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun caused a stir with a self-portrait that depicted her smiling with visible teeth – not very demure for a woman. Le Brun, however, revelled in breaking social and artistic conventions.

Self Portrait in a Straw Hat

after 1782

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

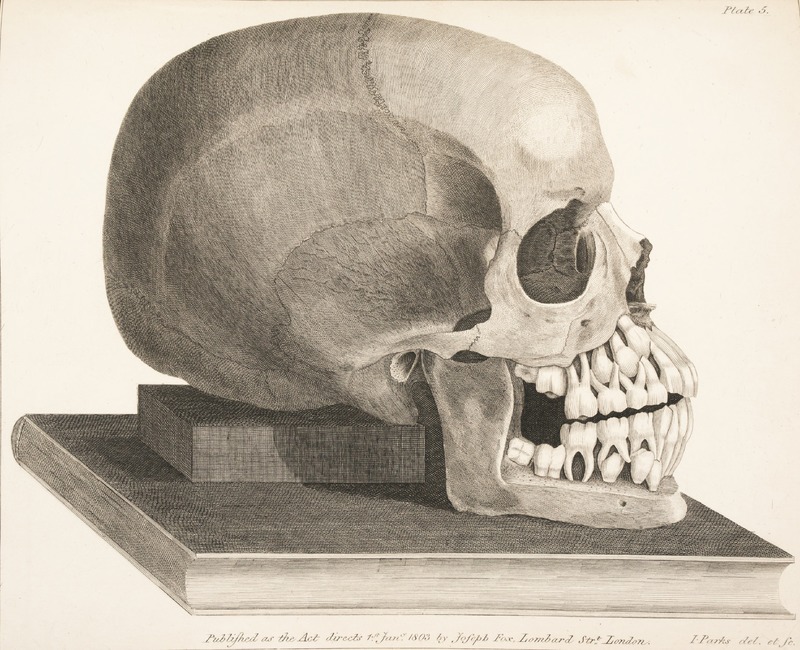

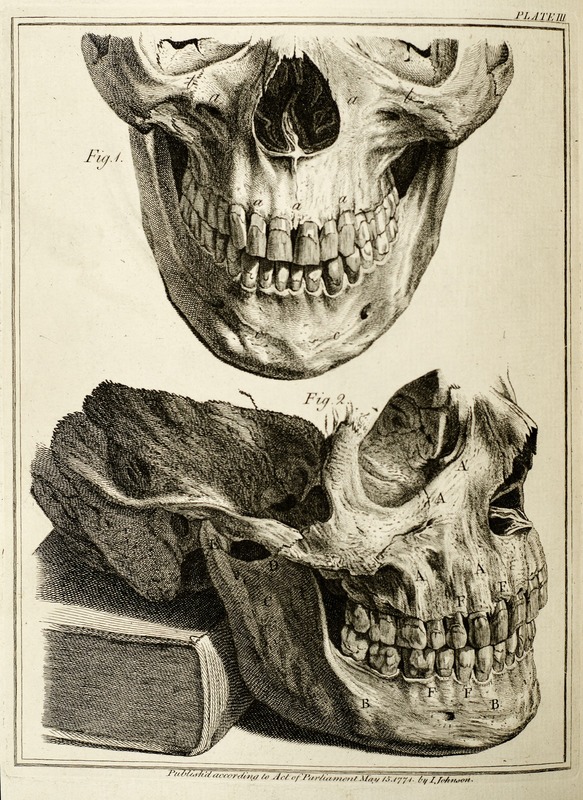

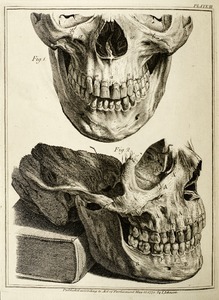

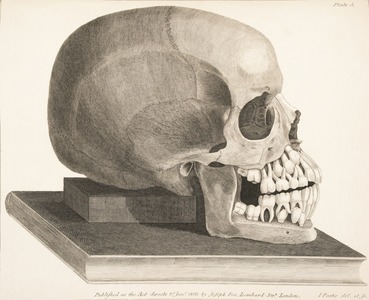

In the 1770s, surgeon and anatomist John Hunter wrote two revolutionary papers which transformed dentistry – the below illustration of a skull and teeth was included in his A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth from 1778. This followed his first book, The Natural History of the Human Teeth in 1771, which examined the structure and development of teeth.

Hunter was the first person to come up with a classification system to describe teeth which is remarkably still used today.

The Hunterian Museum guide on Bloomberg Connects includes an even more detailed image of a jaw, dissected to reveal the roots of the teeth. From 1763 to 1768, Hunter worked alongside the dentist James Spence, advising patients on dental treatment as a way of deepening his knowledge of dental anatomy.

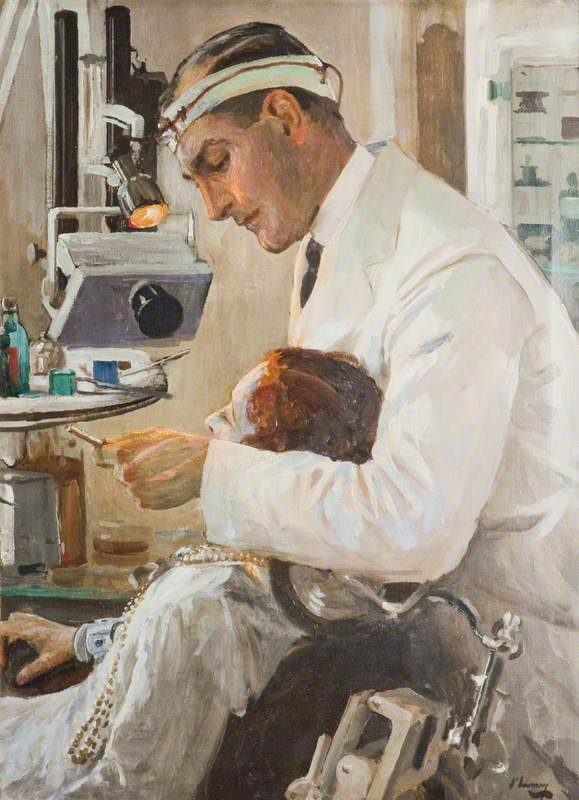

Irish artist John Lavery was known for his society portraits, so his 1929 painting The Dentist marks something of a departure. Set in dentist Conrad Ackner's Welbeck Street practice in London and featuring Lavery's wife as the patient, the painting is a rare example of a work depicting a dentist in action – it even features state-of-the-art equipment used during the early twentieth century, such as X-rays.

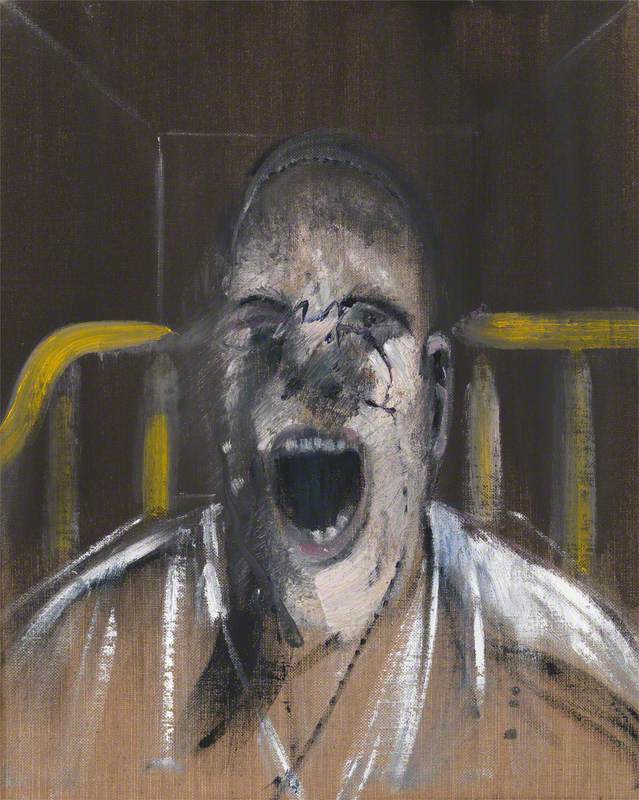

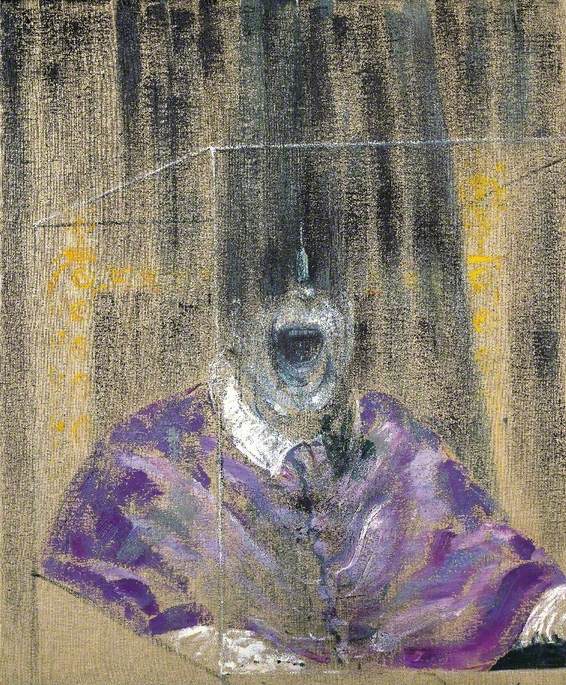

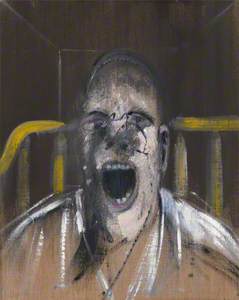

Francis Bacon is well known for his depictions of wide-open, screaming or contorted mouths, which he explored as a way of saying something about the raw, violent, or animalistic aspects of human nature. Bacon was fascinated with the inside of the mouth: in a bookshop in Paris in 1935, he bought a second-hand medical textbook full of hand-coloured plates detailing diseases of the oral cavity.

'I've always been very moved by the movement of the mouth and the shape of the mouth and the teeth [...] I like, you may say, the glitter and colour that comes from the mouth,' he said. His aim was to paint the mouth as Monet had painted sunsets.

Imelda Barnard, Commissioning Editor – Exhibitions and Bloomberg Connects, Art UK

'Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons' is at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 19th October 2025

The Bloomberg Connects app is free to download from the App Store or Google Play. Download Bloomberg Connects today

This content was funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies