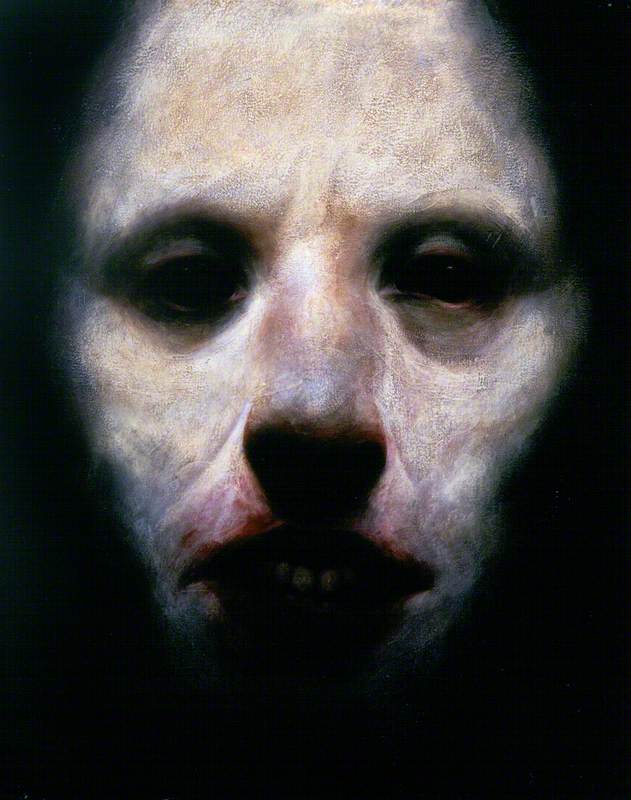

Camille Claudel died on 19th October 1943. Poor and neglected, she had spent the past 30 years of her life living in an asylum on the outskirts of Avignon in France. No one knows exactly where she is buried, other than that her bones were mixed with those of the most destitute, somewhere in a communal grave. Yet since her death, two films, a couple of novels and a ballet have all been created about her life.

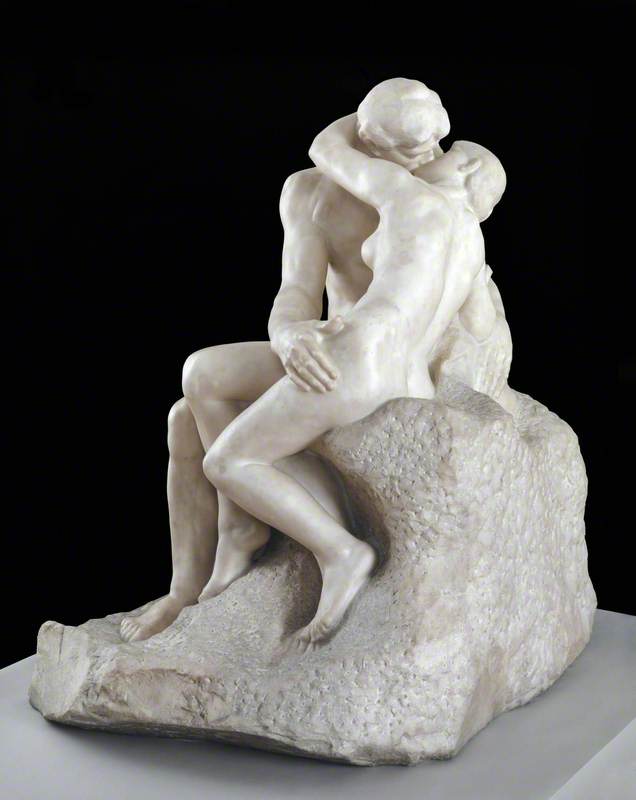

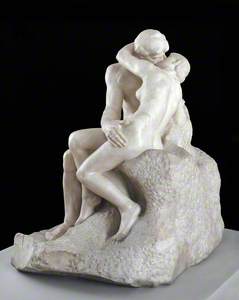

Born in the small village of Fère-en-Tardenois in 1864, Camille was encouraged by her father, Louis-Prosper Claudel, to pursue her childhood passion for sculpture. Her work was so good that the famous Auguste Rodin asked her to become his studio assistant in 1885. Shortly after they became lovers and she began helping him with his work, all the while continuing with her own practice. In 1892 Claudel had an abortion and ended their affair. She began to seclude herself in her studio in an attempt to pull herself out from under Rodin's shadow.

During this time, she made little money and was reliant on financial help from her father. Yet it was during this time she produced what have become recognised as some of her greatest masterpieces.

Works such as L'Implorante which depicts a young woman, naked and on her knees, leaning forward in supplication. Her brother Paul identified the kneeling figure as 'My sister Camille. Imploring, humiliated, kneeling, this superb woman, this proud woman, this is how she is represented.' It is a work widely acknowledged as representing her feelings in the wake of her break-up with Rodin.

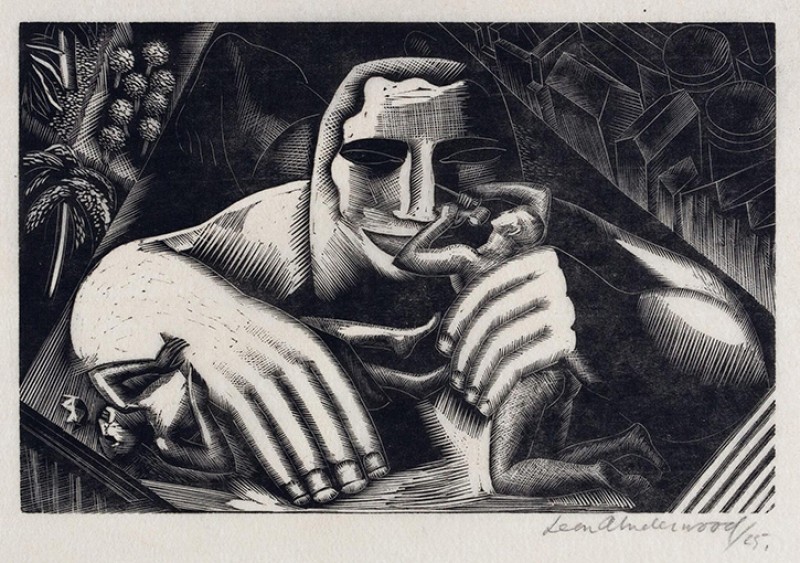

The art critic Octave Mirbeau declared her a genius in the mainstream press. Yet despite this critical recognition, financial success never came in her lifetime, and after 1905 Claudel became more and more reclusive and paranoid. In 1912 she destroyed much of her work. Today, only around 90 works of art by Claudel remain, and it is through these that we know and appreciate her talent. It is a talent which seems to have been driven by an overwhelming desire to express the deep emotions she felt inside herself.

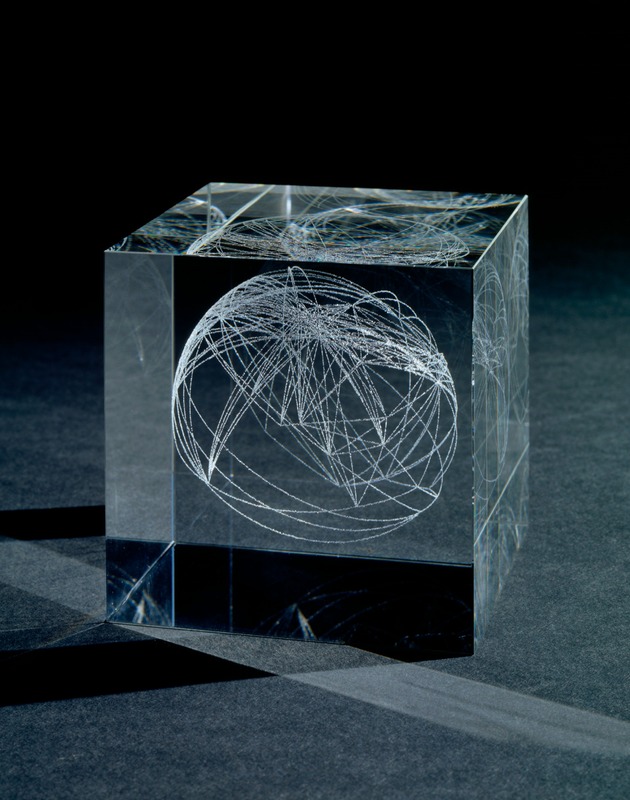

In his 2019 book The Creativity Code, Marcus du Sautoy asks the question, 'Can a machine paint, compose music or write a novel?'

To answer this he proposes a test he coins the 'Lovelace test'. It is named after Ada Lovelace, who began assisting Charles Babbage in his work on mechanical computers after they met in 1833.

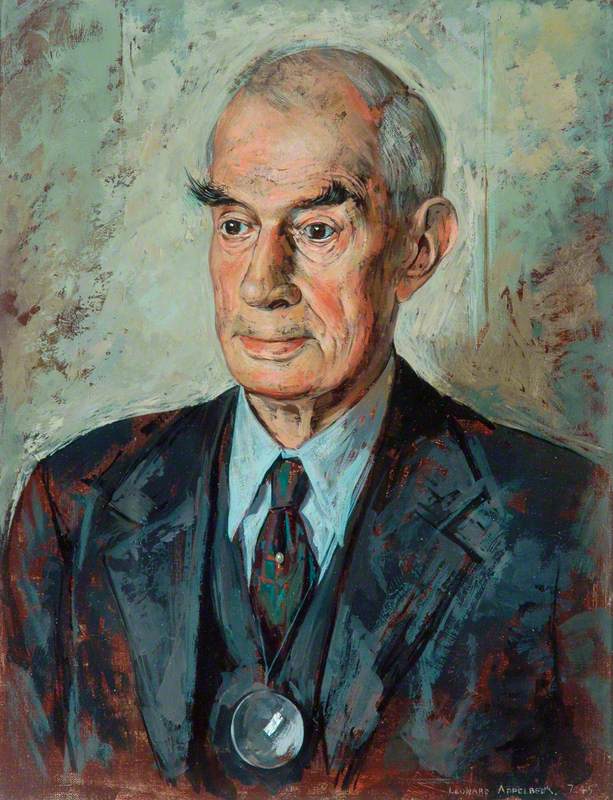

Ada King (1815–1852), Countess of Lovelace, Mathematician, Daughter of Lord Byron

1836

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

She was the first to see the potential applications of machines beyond pure calculation. Du Sautoy believes that to pass the Lovelace test 'an algorithm must originate a creative work of art such that the process is repeatable and yet the programmer is unable to explain how the algorithm produced its output.'

Du Sautoy then demonstrates how machine learning has already succeeded the Lovelace test in spectacular ways. Citing how in 2016 an algorithm called AIVA was the first to be awarded the title of composer by La Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et éditeurs de Musique (SACEM) in France. Created by brothers Pierre and Vincent Barreau, AIVA combines learning with codes from Bach, Mozart and Beethoven and now writes scores for computer games.

April 2016 also saw The Next Rembrandt Project unveiled in Amsterdam. Amazingly, by analysing Rembrandt's existing artwork to understand his style, a new painting 'by Rembrandt' had been generated.

The Next Rembrandt Project utilised deep learning algorithms and facial recognition techniques to create an original 3D-printed portrait by the dead artist.

Large language models continue to evolve in ever more sophisticated ways. So is that it? Will AI eventually produce all our cultural output going forward? Can musicians cease composing, authors put down their pens and artists put away their easels? Well, not quite. First we need to ask ourselves a simple question: What exactly is creativity and why do we need it?

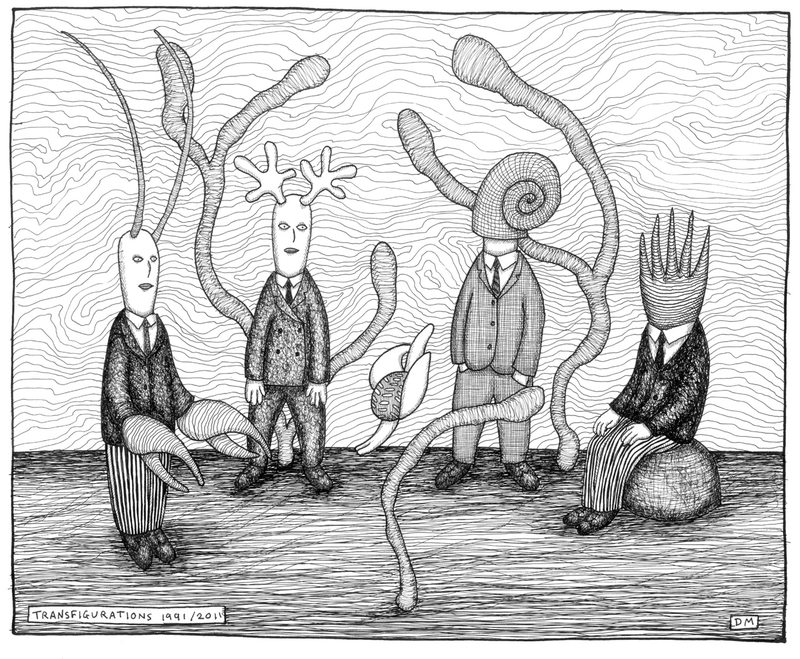

Du Sautoy cites Margaret Boden as having identified three different types of creativity: exploratory creativity, which extends the limits of what we know. Secondly, combination creativity, where two different elements are brought together to create a third new output. And finally transformational creativity, where something goes off at a radical tangent, such as Picasso with Cubism or Schoenberg with atonality.

When we look across history, we see these three differing forms of creativity have been applied in two distinct areas. The first is in problem solving and the second in artistic expression. Since the dawn of humanity, people have been solving problems. Whether finding ways to create fire for warmth or harnessing nature's resources to build bridges, houses and boats. These are the practical things we need to survive.

A Boy Blowing on a Firebrand to Light a Candle

c.1692–1698

Godfried Schalcken (1643–1706)

Alongside this, we have also told each other stories, made music and produced paintings. This is the creativity we use to explore and express our emotions. It is our way of making sense of our own lives and sharing them with others.

AI solves problems, and it can solve them exceptionally well. The earliest AI programs were written by Christopher Strachey and Dietrich Prinz in 1951 to play checkers and chess on a Ferranti Mark 1 computer at the University of Manchester, England. Then, while working at CERN in Switzerland in 1989, Tim Berners-Lee developed the World Wide Web as a computer network for scientists to share information. This subsequently created access to the whole of human knowledge. Available to everyone, everywhere, all at once.

It is this sum of all human knowledge that machine learning models are now able to explore. Because of its speed and reach, AI has gained far greater superiority over people in being able to make new connections, predictions and decisions without being explicitly programmed. AI is now the greater problem solver. So if we have a task, we are typically better off farming it out to a large language model than attempting to solve it ourselves.

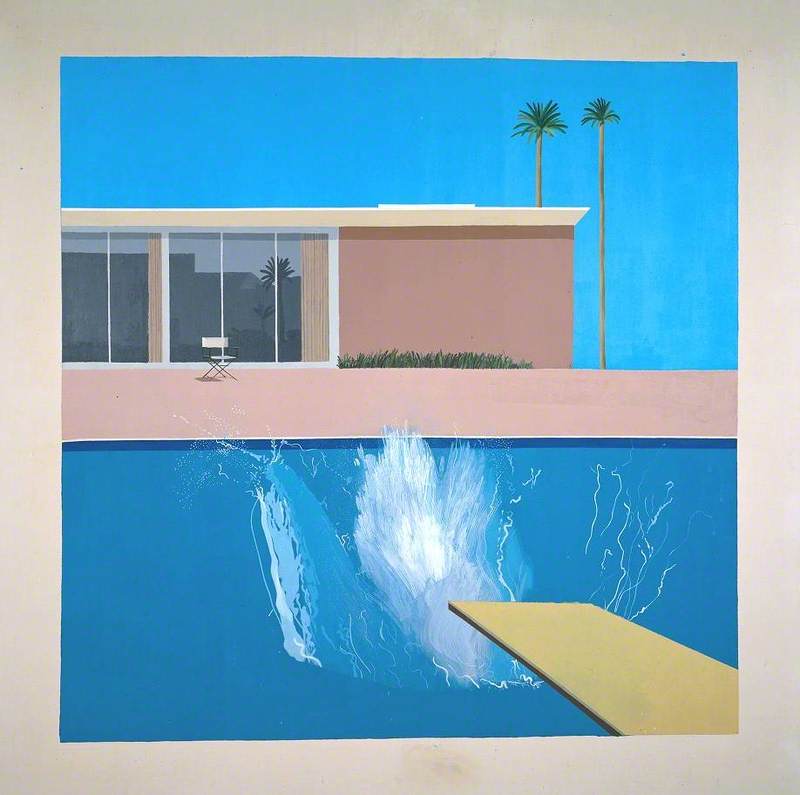

We have seen from the likes of AIVA and The Next Rembrandt Project that AI triumphs in producing creative arts too. Throughout history much of our art was commissioned. And so fits the problem-solving category. Whether it was commissioning Mozart to compose The Haffner Symphony in 1782 or Rembrandt to paint the portrait of Jacob III de Gheyn in 1632. These commissions where problems to be solved.

This is not the whole story, however. While Rembrandt made a fortune in the first part of his life through contracts to paint portraits of wealthy patrons, his circumstances dramatically decreased following the death of his wife Saskia in 1642. He declared bankruptcy in 1656 and was buried in an unmarked pauper's grave seven years later.

Yet it was during these final years that he produced some of his most profound works of art – paintings that are regarded today as amongst the greatest ever made during the past 400 years. Haunting images such as Self Portrait at the Age of 63, which is one of three self-portraits Rembrandt made just before his death in 1669. More than that, they are paintings no one asked for.

If it were only Rembrandt who died in poverty whilst making great art that no one commissioned, we might be able to dismiss it as an aberration. Some kind of historical anomaly. But it is not. History is littered with stories of now-famous writers, composers and artists who lived, worked and died in poverty. We can recall Johannes Vermeer who left his family with huge debts, Van Gogh who famously only sold one painting during his lifetime – or Mozart, Camille Claudel and William Blake.

What then is it that motivates the likes of Jane Austen or Zora Neale Hurston to write novels in obscurity? Or Derek Jarman to create a sculpture garden at Prospect Cottage? Gathering plants, cobbles, driftwood and discarded engine parts together, then rearranging them into unique forms, all while dying of AIDS.

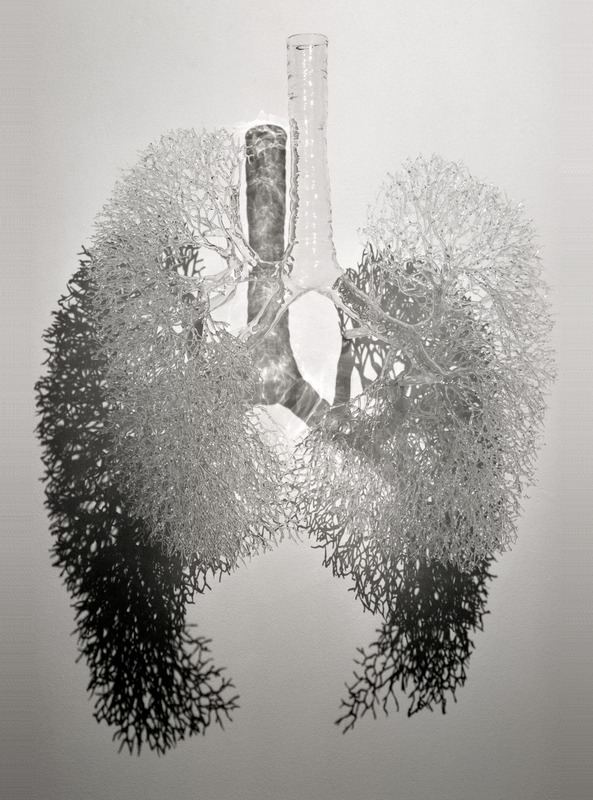

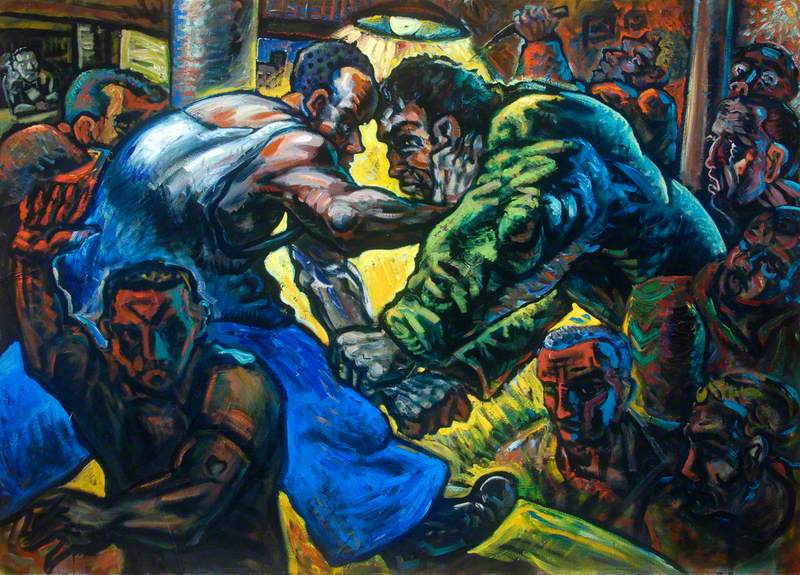

It is simply this, a motivation existed inside these artists which goes beyond sense and reason. They possessed a desire to express something of themselves to the outside world. A desire so powerful and overwhelming they felt compelled to explore the emotions they held inside themselves. To make these feelings manifest in the physical world. Like so many creatives before, and with no commissions to fund them, they drew on simple resources close to hand to make works of art that still speak to us today.

This is the heart of what separates creative AI and human creativity. Creative AI is a problem solver – certainly as it operates in the narrow task-based capacity, of which AIVA and The Next Rembrandt Project made use of. In doing so it has the potential to liberate us from so many mundane jobs. This AI is commission-driven, free from emotion and only exists in machines – while we are confined to our bodies. Bodies which can feel tired, stressed and grow old.

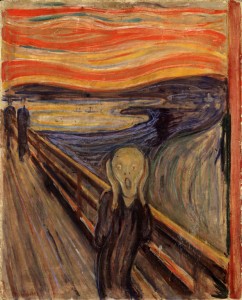

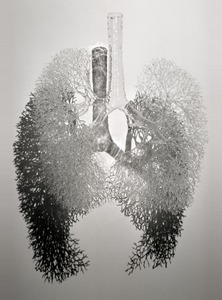

We experience emotions like love, hate and fear, which we have little or no control over. We often don't understand them and it is our desire to understand our passions that drives us to make art. It helps us to rationalise. In both making art and engaging with the art that others have made, we find new ways to make sense of a complex social and emotional ecosystem. For many of us there is a spiritual element to creativity too.

So how do these deeply personal outpourings relate to the great works of art that have been commissioned and which also manage to connect with us at an emotional level? How are works like Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel or Leonardo's The Virgin of the Rocks able to move us in the same way? I believe this takes place when a great artist is able to graft their sensitivities onto a commission. When the task assigned aligns with the artist's emotions, the potential for an exceptional and profound outcome emerges.

In the future AI may be able to achieve this too, as it becomes ever more effective at imitating our human sensitivities. Indeed, it may go much further, as large language models evolve from narrow AI towards general intelligence and superintelligence. In this future, we can imagine a potential where AI-implanted robots gain full autonomy and evolve their own consciousness.

If this happens, they will become a new species in the world. And who knows, they may develop a desire to explore and express their own lived experiences through the creation of art, just as we do. This will not be our art though, it will be an art of AI cognisance. And it will be a fascinating new world to witness.

As our technology advances it offers the promise of leaving us with more free time. Time for leisure and time to explore the creative impulse that drove Mozart, Rembrandt and Claudel to make exquisite music, paintings and sculptures. Perhaps more time to make new works of art which express our emotions, just for the hell of it.

Robert Priseman, artist, collector, writer, curator and publisher