In 1900, three men travelled from London to Ostia in the countryside near Rome to take part in an experiment to test a theory that malaria is transmitted through mosquitoes. The trio consisted of Dr Louis Westenra Sambon and Dr George Carmichael Low, experts in tropical medicine, and Amedeo John Engel Terzi, an artist engaged to illustrate the mosquitoes, parasites, and findings that emerged from the experiment.

For three months, from July to October, the men were to reside in a mosquito-proof hut in the marshy, malaria-infested area south of Rome. At the time, the word 'malaria' – from the Italian mal aria, or 'bad air' – reflected a belief that the disease was caused by poisonous fumes rising from stagnant water. Though scientists had begun to suspect otherwise, the exact process of transmission remained unproven.

Three Members of the Roman Campagne Malaria Commission Carrying Their Gear

c.1900

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

After only three weeks in the hut, all the men contracted malaria. The hut had been built to test whether they could avoid the disease by preventing mosquito bites. In a twist that supported their hypothesis, the mosquito-proof hut failed, or, more accurately, they had miscalculated just how difficult it was to keep every mosquito out. Their illness reinforced the idea that malaria wasn't airborne at all but rather spread through the bite of a specific kind of mosquito: the female of the genus Anopheles.

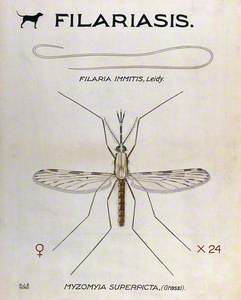

The experiment had been designed by Sir Patrick Manson, a Scottish physician whose research was the basis for the emerging field of tropical medicine. Manson had already shown that mosquitoes could transmit parasitic worms and became increasingly convinced that they also played a role in malaria.

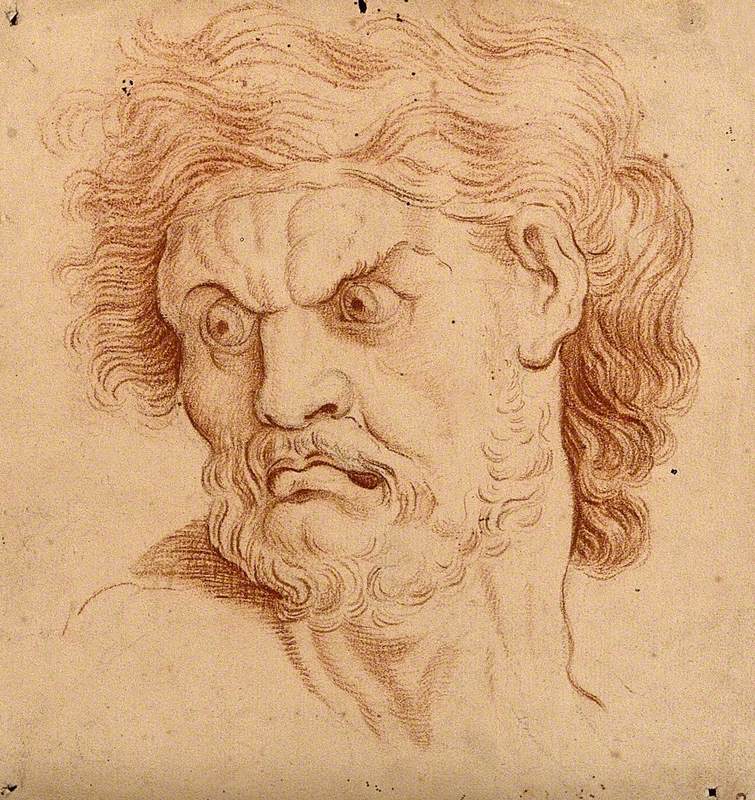

Sir Patrick Manson (1844–1922), Investigator of Tropical Diseases

(after W. B. Webster) c.1900

Harry Herman Salomon (1860–1936)

In 1899, he opened the London School of Tropical Medicine with the goal of training doctors who would be stationed throughout the British colonies. With his colleagues Sambon and Low, Manson began testing the mosquito-malaria theory through controlled exposure experiments with human 'volunteers' – his preferred term.

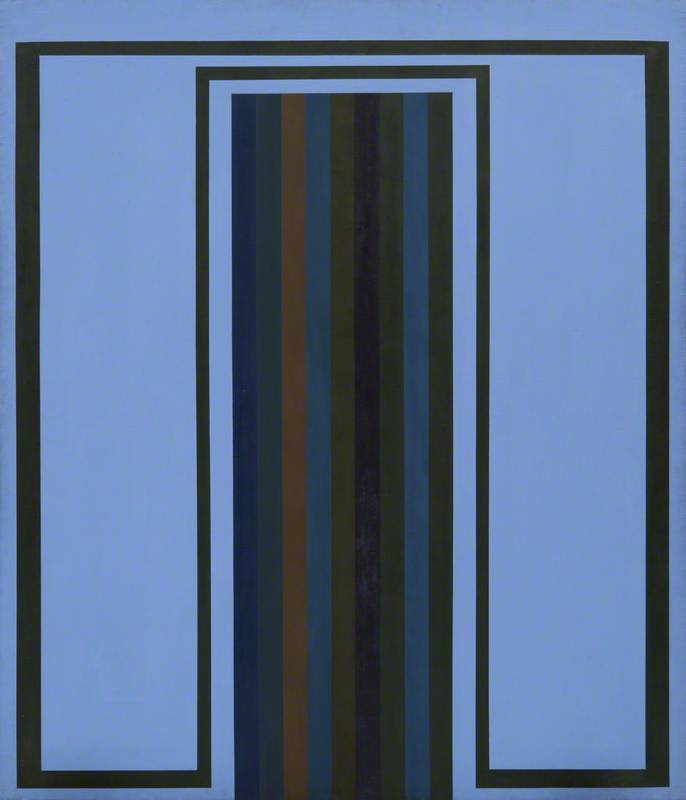

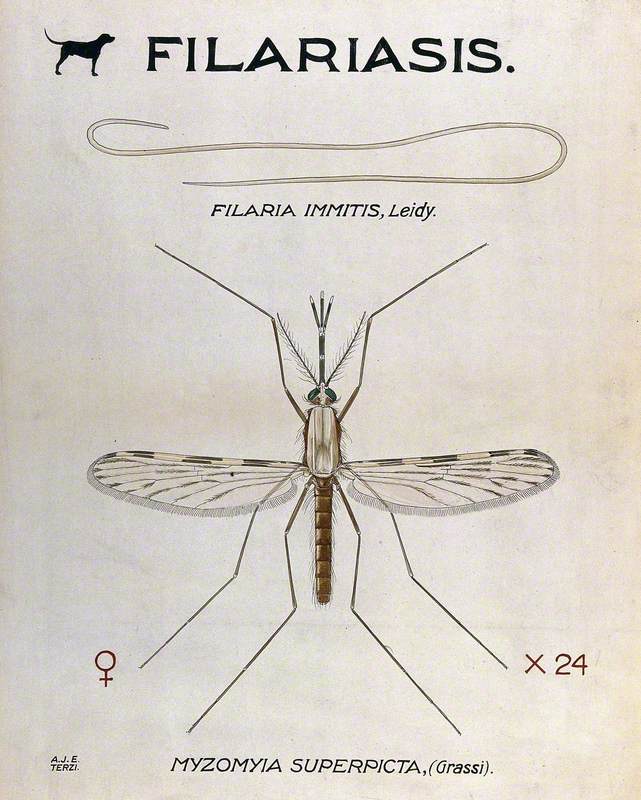

A Parasitic Nematode (Filaria Immitis) and Its Vector, the Mosquito (Myzomyia Superpicta)

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

Among the first was Manson's own son, who was deliberately infected by a mosquito bite and quickly treated with quinine, the primary accepted treatment for malaria at the time. Extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree, quinine had been used for centuries to reduce fever and chills, and its inclusion in the experiments served both as a safeguard for participants and as further confirmation of infection when symptoms responded to the drug.

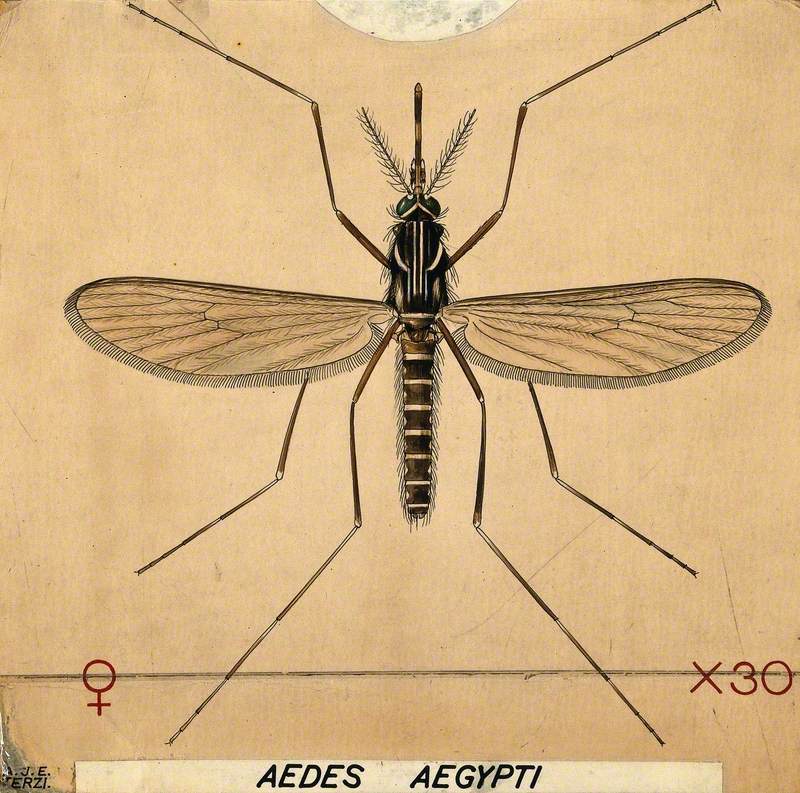

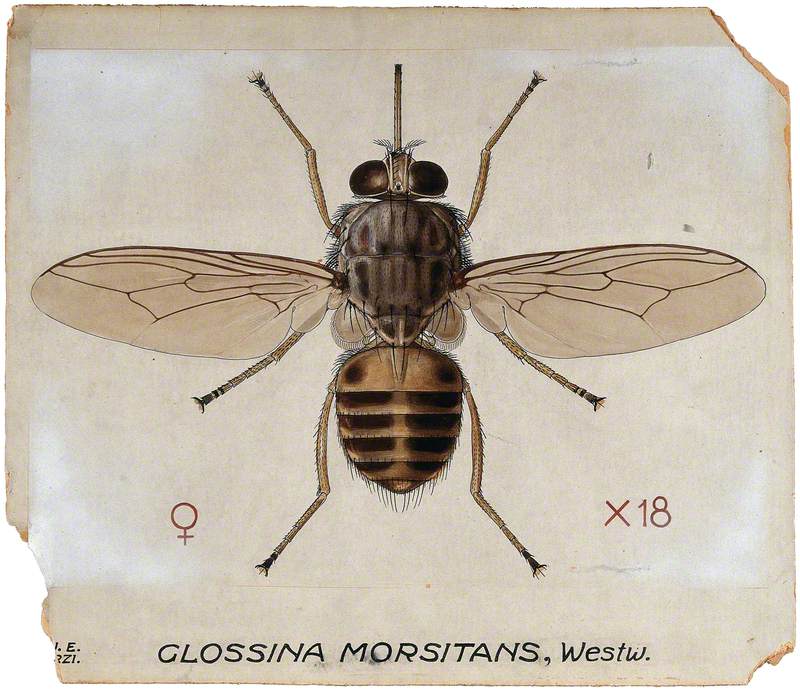

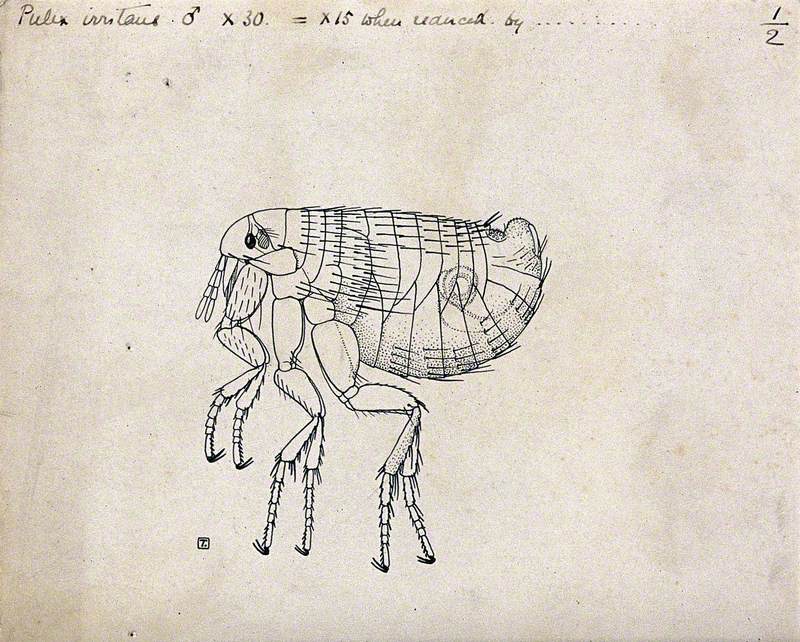

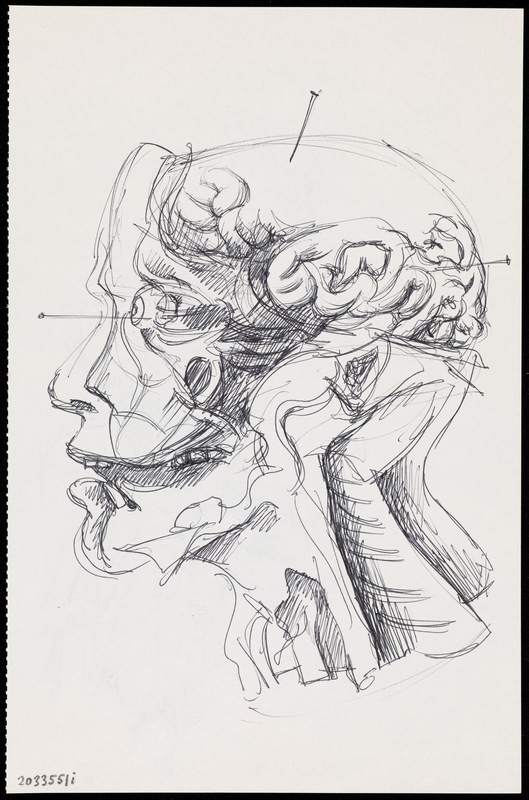

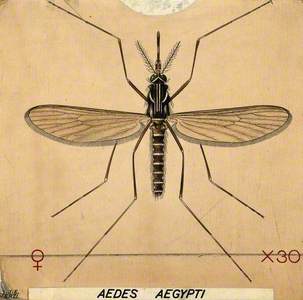

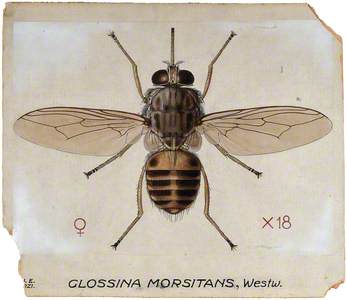

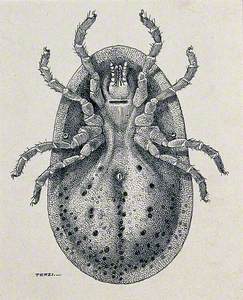

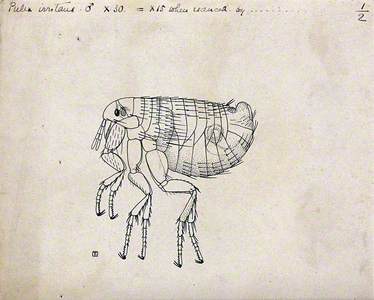

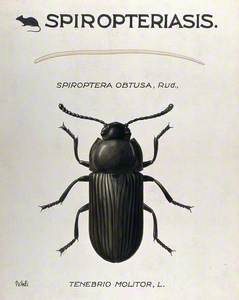

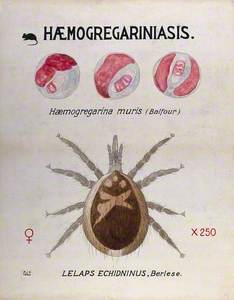

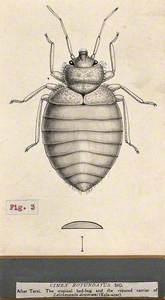

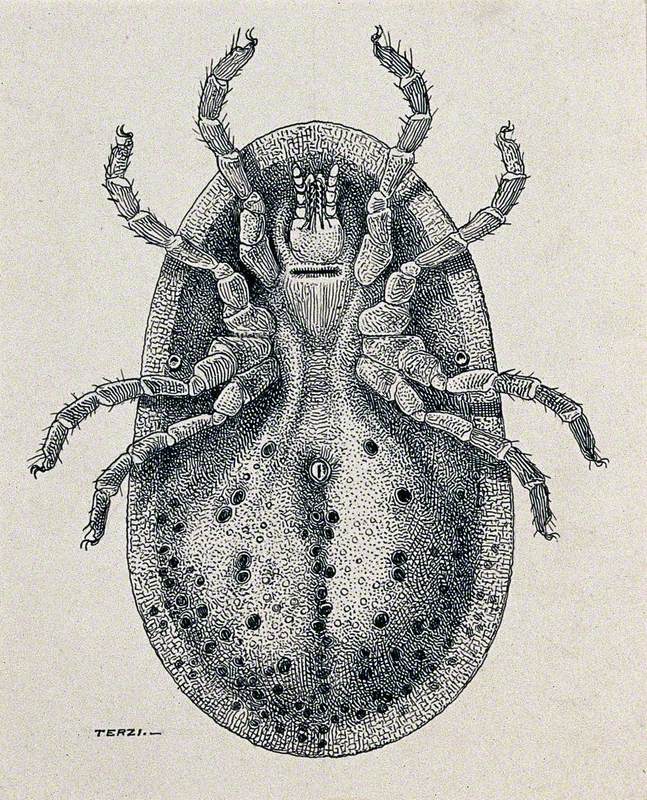

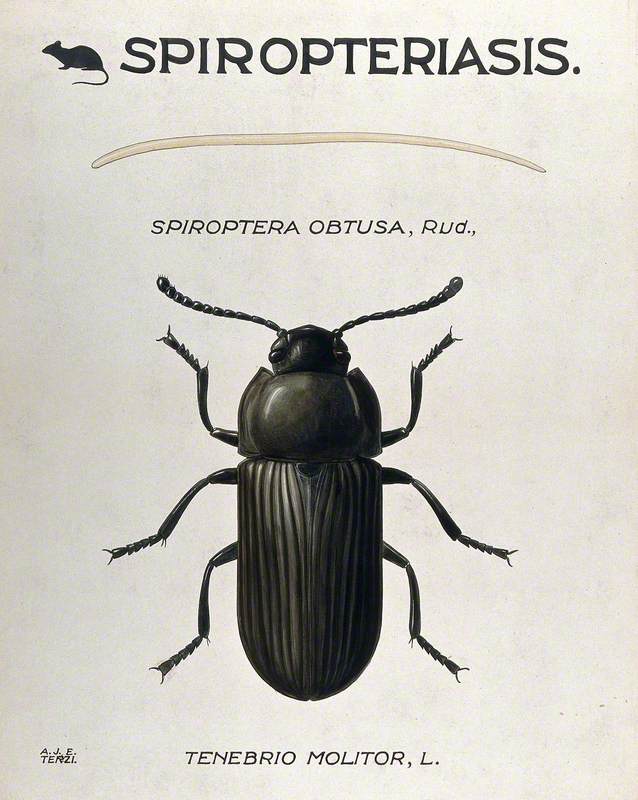

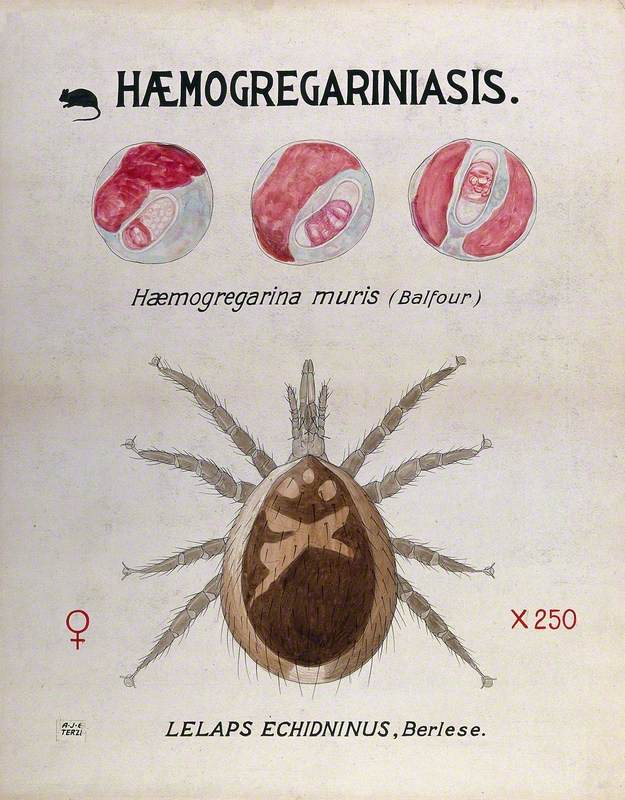

A vital component of these experiments was the ability to observe and accurately document the mosquitoes involved. At the turn of the century, photography lacked the resolution to capture fine insect anatomy and tiny distinctions that were crucial in determining which species transmitted disease. Instead, hand-drawn illustrations became key tools.

Artists like Terzi provided intricate details from the fine webbing of a mosquito's wing to demonstrating how they acquire pathogens from an infected host and subsequently transmit them to a new host during feeding. Whilst these images were beautiful and impressive, their purpose was to serve as scientifically precise documents that helped identify and differentiate species.

A Ventral Aspect of the Female Fowl Argas (Argas Persicus)

c.1919

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

The exact circumstances of how Terzi became involved with the malaria experiment remain unclear. What is known is that he was born in Palermo in 1872, into a family of artists. His father was a lithographer, and his brother contributed insect illustrations to Italy's national encyclopaedia. Amedeo claimed to have taught himself most of his skills – painting, architecture, engraving, anatomy and zoology – through study and practice.

He was working in Italy when his drawings for a paper by Sambon and Low were sent to Manson, who was impressed enough to invite Terzi to England. He landed in London in November 1900 and formally joined the School of Tropical Medicine staff a month later.

Terzi's tenure at the school was brief, as he left in 1901 for unknown reasons, but his impact was lasting. The following year, he was invited to join the British Museum's Department of Natural History (now the Natural History Museum), where he remained for the rest of his career, aside from a short break during the First World War.

By the time of his death in 1955, Terzi had produced over 37,000 drawings, illustrated nearly 55 books and more than 500 scientific papers, and created wax models and coloured displays that were exhibited in museums around the world. He had a reputation for being curt and was not inclined to small talk with colleagues, yet his fondness for Sambon endured for decades. He regarded him as a mentor and credited him with launching his career in scientific illustration. After Sambon's early death in 1931, Terzi remained in touch with his family in both Italy and London.

The Larva of a Flesh Fly (Sarcophaga Species)

c.1919

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

Entomological illustration served more than one purpose. Beyond the lab, Terzi's drawings were used to teach students and train public health workers, helping them learn to identify dangerous species and understand how transmission occurred. The visual representation of the parasite's life cycle, from mosquito to human and back again, was an essential development. Before the advent of high-quality imaging, illustration didn't just support science – it revealed it.

A Parasitic Worm (Filaria Species) and Its Vector Beetle (Tenebrio Molitor)

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

Terzi's best work was arguably the images he created to accompany the book Illustrations of British Blood-Sucking Flies in 1906, written by Ernest Edward Austen. The images had originally been intended to hang in public galleries, but Austen deemed the art worthy of a special publication.

Life Cycle Stages of the Parasite Haemogregarina Muris and Its Vector, the Mite (Lelaps Echidninus)

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955)

Despite his enormous contributions, Terzi remained largely in the background, and no obituary was published when he died in 1955. In 1908 he had married Virginia Irving Stauder, daughter of an Episcopalian American clergyman who had retired to London, and they had a son. Virginia had died in 1944 in a private mental hospital in Peckham. He is rarely mentioned in histories of science or art despite his work helping establish a breakthrough for early tropical medicine.

Entomologist Gordon Floyd Ferris praised Terzi and his talents in the 1928 book, The Principles of Systematic Entomology. He wrote: 'This illustrator is one who combines the qualifications of both the artist and the scientific investigator to such a degree that his illustrations are not only pleasing to the eye but technically impeccable as well.' Ferris went on to suggest that any student interested in the field of entomology should study the work of Terzi.

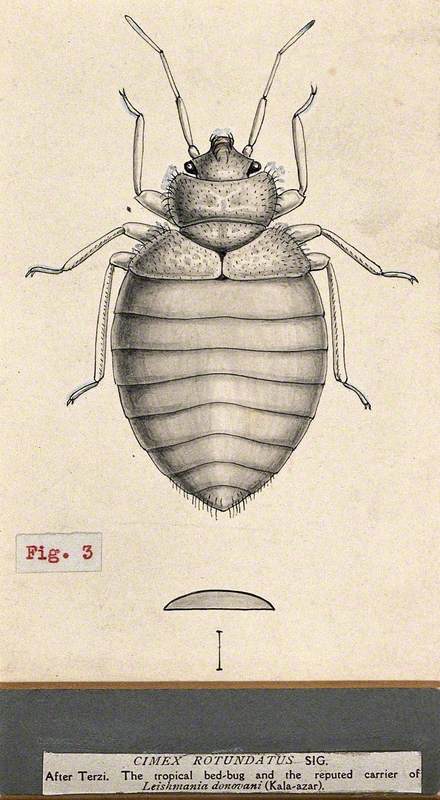

The Tropical Bedbug (Cimex Hemipterus)

c.1919

Amedeo John Engel Terzi (1872–1955) (after)

Whilst much has changed in our understanding and treatment of malaria today, the foundations were laid by early pioneers like Manson and made visible by illustrators like Terzi. Though Manson's theory wasn't 100% proven by the Italian experiment, it established essential groundwork and strongly supported the hypothesis that mosquitoes are transmitters of malaria. Terzi's illustrations played a pivotal role in this scientific milestone, bridging the gap between theory and visual understanding in a time before modern imaging.

Cortney Ellis, writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Lise Wilkinson, 'Illustrations from the Wellcome Library: A. J. E. Terzi and L. W. Sambon: early Italian influences on Patrick Manson's 'Tropical medicine', entomology, and the art of entomological illustration in London' in Medical History 46, 2002, 569–579

Jaime Jaramillo Arango, 'The History of the Mosquito-Malaria Theory I' in International Journal of Clinical Practice 2, 1948, 345–348

Peter Mattingly, 'Amedeo John Engel Terzi' in Mosquito Systematics 8(1), 1976, 114–120

William Bynum, 'Experimenting with fire: giving malaria' in The Lancet, Volume 376, Issue 9752