'We are the strange ones, with half of our beings always in the spirit world'

– Ben Okri, The Famished Road (1991)

Rotimi Fani-Kayode's photographic practice was as much a rich self-reflective exploration of the Black male body as it was an insight on race, sexuality and contrasting belief systems between the West and the global South. The enduring legacy of Rotimi's photography lies in its ability to spark broader discussions on notions of identity, displacement and belonging.

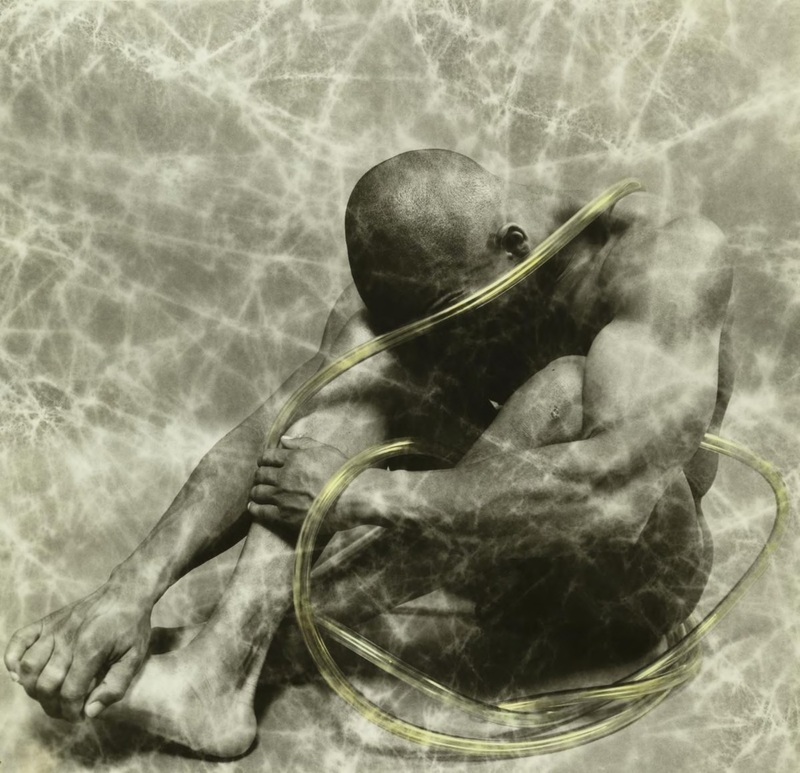

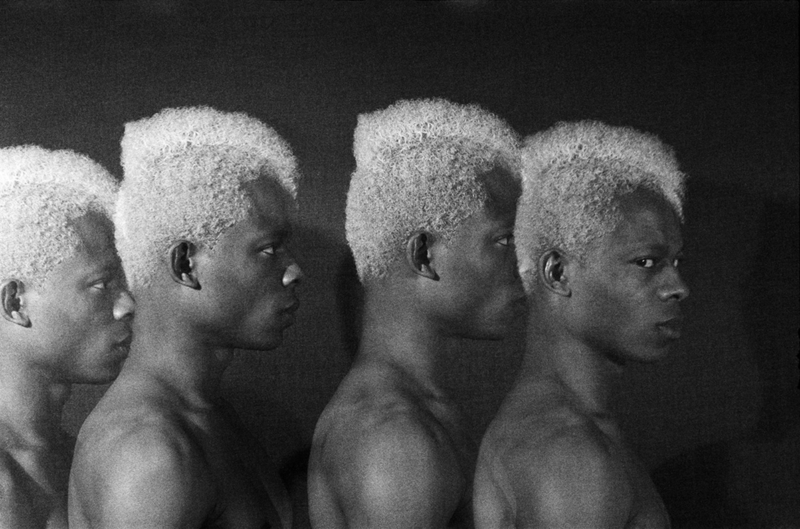

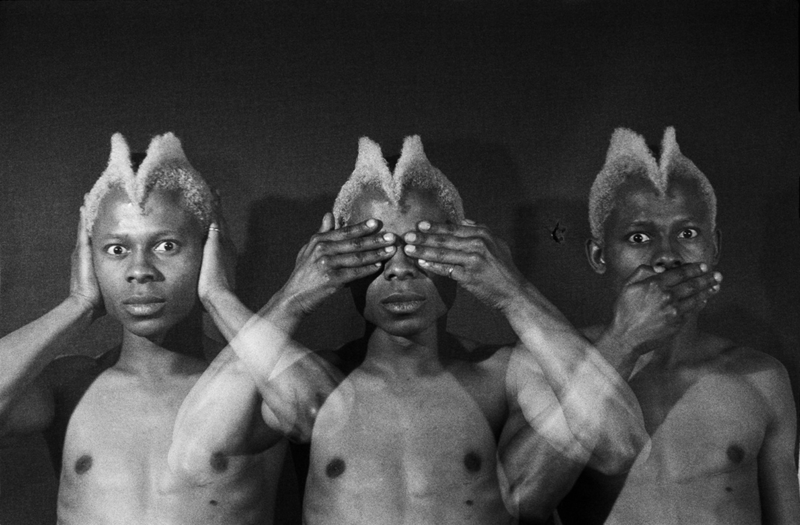

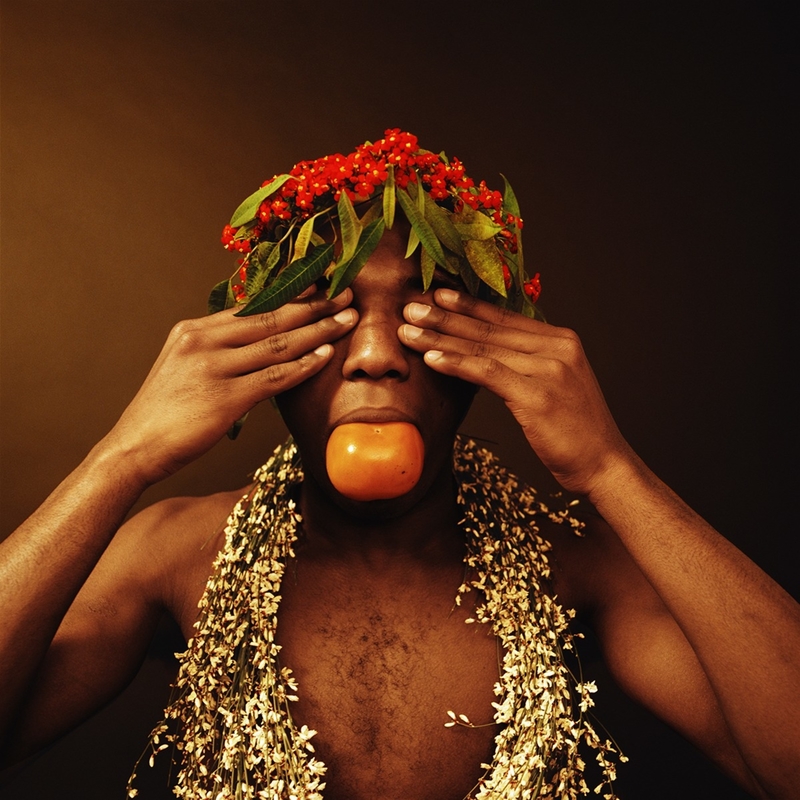

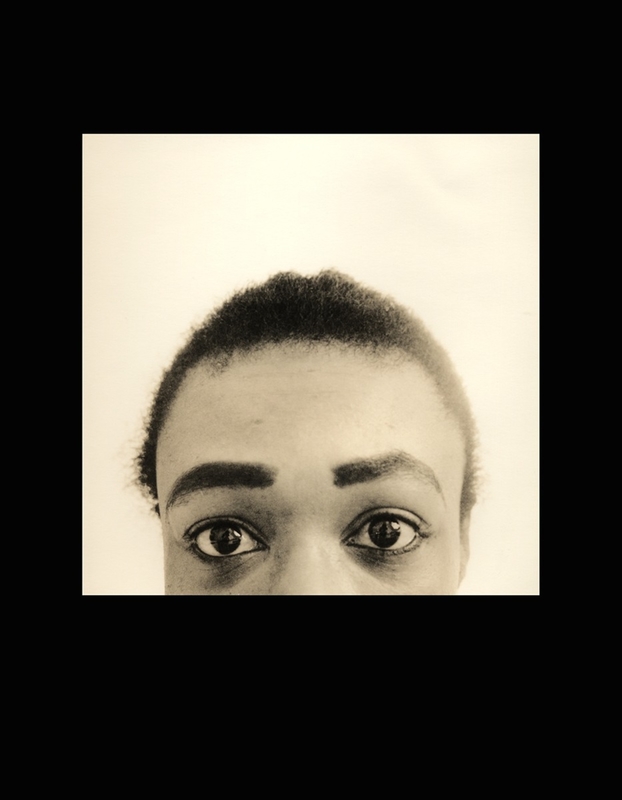

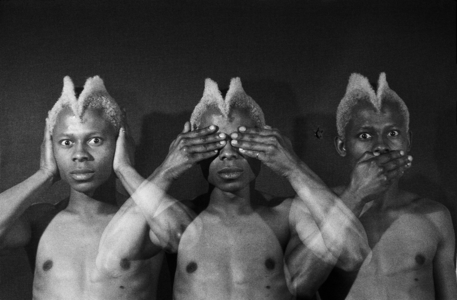

This short analysis of Fani-Kayode's photographic series Abiku (Born to Die) (c.1988) locates these artworks within traditions of his Yorùbá heritage and mythologies. Born in 1995, in Lagos, Nigeria, Rotimi's name, meaning 'stay (and put up) with me', can also be attributed to the Yorùbá tradition of the spirit child, the Abiku. 'Fani' connotes Ifa, the orisha deity and divination practice of offerings within Yorùbá cosmology – traditions that emanate from Yorùbá ancestral titles bestowed on the Kayode family.

This analysis also explores ideas of exile and errantry (wandering) through the mythology of the Abiku. Their elusive nature is evident in contemporary Nigerian literature, as seen in Wole Soyinka's poem Abiku (1967), where the Abiku taunts the use of offerings to prevent him from returning to the spirit world. Soyinka's poem provides a means by which to draw parallels to the perceived shame felt by Rotimi Fani-Kayode's parents, of him not fulfilling the expectations they held for him and due to his sexuality.

In Ben Okri's The Famished Road (1991), Azaro the Abiku lives in exile from the spirit world, and it is only through an early death that he can return. Allegorically, Okri's book raises notions of the sociopolitics of tradition, versus or within modernity, and is a useful narrative device when attributed to interpreting Rotimi's photographic series.

The mythology of the Abiku also situates Rotimi and his family within discourses of exile; they had to move to England due to the Biafran and Nigerian civil war of 1967–1970. In Bloodflowers (2019), critic Ian Bourland recounts how Rotimi's nomadic lifestyle took him to Washington DC, first to study in the mid-1970s. In DC, and later New York, he was seduced by avant-garde and surrealist subcultures. In 1983, he returned to London, where he resided until his premature death in 1989.

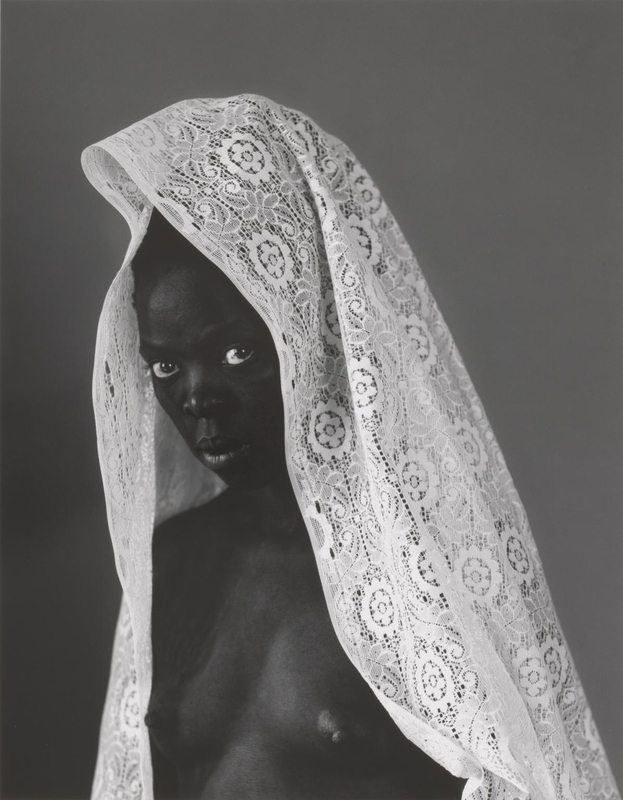

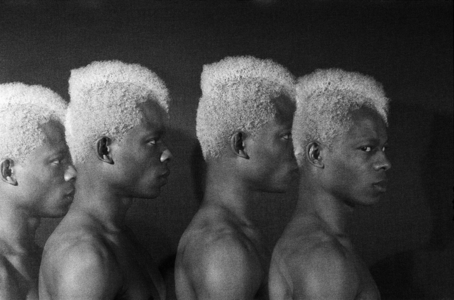

The symbolism of Rotimi's Abiku can be read as a contemplation of his mortality and that of other gay men during the AIDS/HIV epidemic of the 1980s. In Abiku, we probe the liminal spaces of the spiritual and physical world, in exploration of Rotimi's representations of Black masculinities and sexualities. In his essay Traces of Ecstasy (1992), he reveals his use of Yorùbá traditions and European art history are in celebration of 'Black, African, Homosexual photography' – in defiance of binary and heteronormative assumptions.

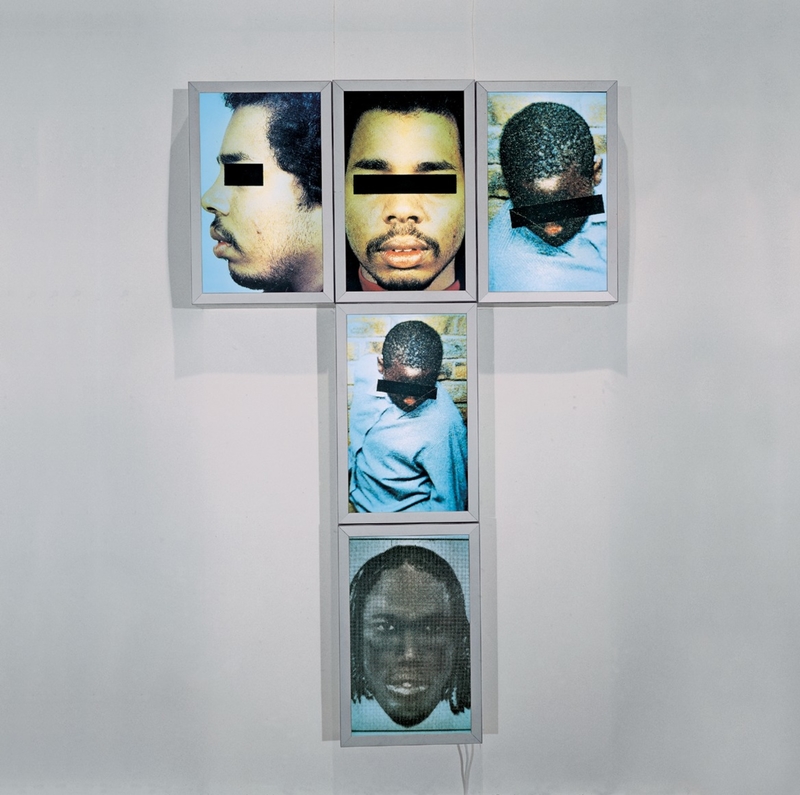

This defiance was underpinned by the photography journal Ten.8, which declared the 1980s a 'Critical Decade' for the art form. Ten.8 editors Stuart Hall and David A. Bailey argued Black documentary photographers had pushed the genres' boundaries through their practice, by decentring the subject and the emerging plurality of identities, which challenged the Eurocentric gaze and the supposed objectivity of the genre of Western documentary photography.

While Black photographers such as Vanley Burke and Charlie Phillips are famed for their documentary style, capturing the Black British lived experience, conceptually, Rotimi represented a paradigm shift in Black photography.

With an eye for the dramatic and the avant-garde, Fani-Kayode's Black homoerotic photography was infused with Yorùbá motifs and Western/Christian iconography, referencing colonialism's violent collision with the African continent. For example, dichotomies of religion, gender and sexualities are illustrated in the tender neo-classical/neo-romantic tableaux of Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies) (1989) and the provocative Golden Phallus (1989).

However, for Fani-Kayode, the Black male body was not an object for Eurocentric desire to be exploited for its virility. Images such as Golden Phallus critique the objectification of the Black male body, echoing Franz Fanon's provocation (in Black Skin, White Masks, 1952) of the Black man being reduced to his sexual prowess. Instead, Fani-Kayode sought to highlight to his own people and the West that African and Black men could desire each other.

Being of Nigerian heritage, Fani-Kayode challenged historical essentialist notions of Black identities in Britain. Educated at elite British schools and Georgetown University, USA, and with his family's ancestral Yorùbá standing, Fani-Kayode's upbringing, ancestry, and heritage may have set him apart from many African-Caribbean descendants of migrants who settled in post-war Britain.

However, the homogeneous view of Blackness in 1980s Britain drew no distinction between Fani-Kayode's Nigerian heritage and African-Caribbean migrants, whose descendants, as first-born Black British youth, found their progress in Britain's cities obstructed by historical and social constructs of race. These descendants would emerge as a generation who contested ideas of Britishness and belonging.

Returning to London in 1983, and as an activist, Rotimi would have witnessed the counterhegemonic, countercultural artwork and discourses (for example, the Blk Art Group, c.1979–1984), activism and civil uprisings in Black communities of Brixton, Handsworth and St Paul's in 1985. However, as a gay Nigerian, Fani-Kayode recalls how he remained an 'outsider' in a binary Black British experience.

Although an 'outsider', Fani-Kayode was among the generation of Black women artists (such as Ingrid Pollard, Lubaina Himid, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson) and gay male artists (Isaac Julien, Sunil Gupta, Hanif Kureshi) who represented the notion of 'new ethnicities' – where previous fixed understandings of gender, sexuality and what it means to be Black and British were contested. It is through this lens, and the Black male body of the Abiku series, that we can begin to grasp how Fani-Kayode questions such meanings.

For Fani-Kayode, the Black male body represented a disputed body, characterised by the refusal of The Photographers' Gallery to exhibit his photography on more than one occasion. As Mark Sealy explains in Decolonising the Camera (2018), the gallery deemed his practice a 'poor imitation' of Robert Mapplethorpe.

Fani-Kayode also spoke of the disquiet and homophobic response to his photography from both Black and white communities. This was exemplified by the decision of intercultural arts magazine ARTRAGE (1982–1995) to publish only one of Rotimi's photographs, due to what John Akomfrah states, in his Ten.8 article 'On the Borderline' (1991), as the 'needless offence' his photographs might cause. This experience perhaps illustrates the binary discourses of gender and sexuality permeating within the perceived progressive sector of Black and South Asian arts practice.

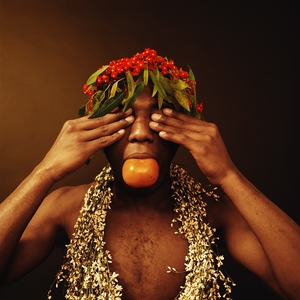

Turning to his practice and speculating on the influence of the avant-garde and surrealism, Ian Bourland's 2022 article 'Surrealism and the Specter of Death in the 1980s' suggests we might appreciate how Fani-Kayode mediated between contested worlds. By drawing parallels between Fani-Kayode and 1960s Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe, Bourland alludes to Hosoe's use of the surreal, and the possible influence on Fani-Kayode's practice, through similar images of dislocated bodies, respective references to mythologies of Yorùbá and Buddhism, and flower motifs.

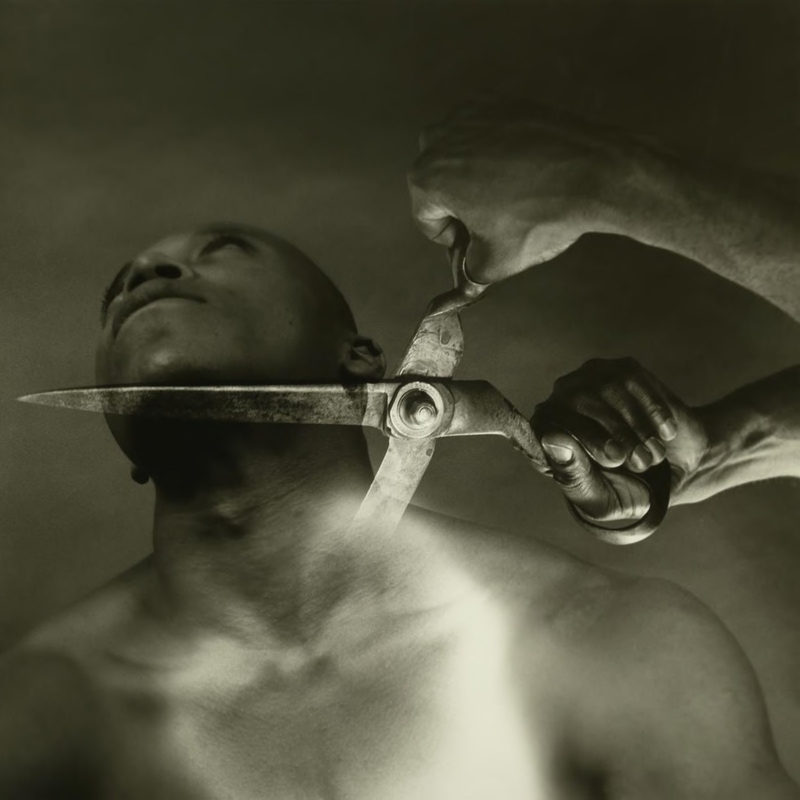

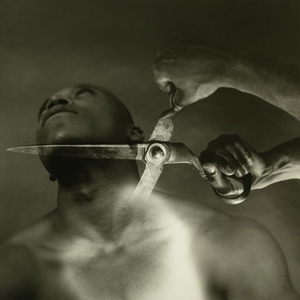

Thematically, further comparisons are drawn in respect of the speculation of death, alienation and infection. For Hosoe, it was the exposure to particles of 'nuclear fallout' in post-war Japan. For Fani-Kayode, it was the AIDS/HIV epidemic of the 1980s. The following selected photograph from Fani-Kayode's Abiku photographic series allows us to hypothesise on this meaning

In the photograph, we see the superimposed violent action of oversized shears cutting across the Black male model's neck. Shears appear as a prop in Rotimi's works, such as Offering (1987) and another untitled image in Akomfrah's 'On the Borderline' article. Do the shears symbolise the Black gay body in conflict with Christianity and Fani-Kayode's Yorùbá heritage at the height of the AIDS/HIV epidemic?

The shears may also speak to the political weaponisation of sexuality. In 1988, the Conservative government introduced Section 28 of the Local Government Act, banning local authorities from promoting homosexuality. Therefore, when wielded by Black hands, could the shears allude to the anger felt towards same sex relationships, by what Kobena Mercer regards, in Welcome to the Jungle (1994), as certain sections of conservative-minded Black British people?

Rotimi's photographs Nothing to Lose XII (Bodies of Experience) (1989) and Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies) (1989), in addressing the impact of AIDS, are also crucial in challenging the historic and monolithic assumptions of race, gender and sexuality. By arguing his 'reality' differs to that which is often presented in Western photography, we can regard this as a reference to notions of 'difference' and Fani-Kayode's attempt to release the Black male body from the fetishised white Western gaze, towards a more tender and vulnerable portrayal of Black masculinity, to which his diasporic lived experience would attest.

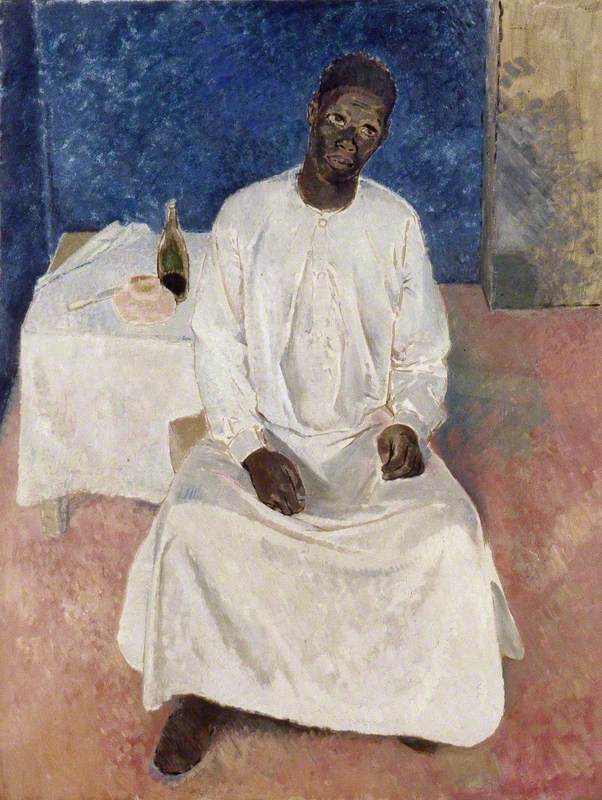

Rotimi Fani-Kayode thus subverted the surrealist endeavour of seeking new ways to push the boundaries of modernism, by means of appropriating artistic styles of African art spirituality deemed as primitive. His return to London in 1983 can be likened to that of African American, African, and Caribbean migrants settling in Europe after the First World War.

Fani-Kayode's presence in Britain, like his artistic predecessors in Europe, unsettled 'easy assumptions' of so-called primitivism (as Brent Hayes Edwards phrases in journal Transition, 1998). Due to his heritage, he already possessed authenticity and gained knowledge of magical rituals, desired and appropriated by European modernists.

In his essay Traces of Ecstasy (1992), Fani-Kayode declared his images of 'smallpox gods, transexual priests, and desirable Black men in a state of sexual frenzy would probably be better understood in the rural villages of Nigeria', implying these manifestations, mythologies, imagery and ways of being have always existed – only becoming surreal when transplanted to and appropriated in the West.

Discourses of exile, displacement and errantry conclude the critique of the Abiku (Born to Die) series, and where we gain further insight into Fani-Kayode, the Black male body and sexuality. Through his practice, we are confronted with identities that have always existed, destabilising fixed and essentialised notions of Blackness which have been historically conflated in Britain. Fani-Kayode's photography demands the Black community confront its reticence and 'violent ambivalence' (as Kobena Mercer states) towards Black male desire and sexuality.

The Abiku series articulates an 'unbridgeable dislocation' from his parents, his Yorùbá heritage and to Nigeria, and speaks of the 'loss' of home and love. However, as Edward W. Said suggests in Reflections on Exile (2013), perhaps what was gained is a 'plurality of vision' in seeing the world as an 'outsider'.

Of errantry and exile, Édouard Glissant argues in his 1997 work for the 'poetics of relation' of 'rhizomatic thought' and where every identity is realised in relation to the 'Other'. However, Western civilisation, though realised through nomadism and conquest, soon reverts to 'rootedness' of a nation state and a fixed identity. Whereas, Fani-Kayode's transatlantic sojourn through communities and subcultures in America and London embodies a rhizomatic intent, in search of identity and in relationship with the 'Other'.

In the pursuit of the 'Other', Fani-Kayode writes of his activism for social justice in respect of race and sexuality. In doing so, the suggestion is that one may also 'find oneself', as well as give voice to the 'powerless' (as Glissant phrases). In 1988, Fani-Kayode became the first chair for Autograph, previously known as the Association of Black Photographers, based in London.

In recognising he is an 'outsider', and titling a series of photographs Abiku (Born to Die) and Nothing to Lose, Fani-Kayode embraced his positionality as a lens through which he articulates the contradictions inherent in the historical Western fetishisation of the Black body – while simultaneously, the art world denounced Fani-Kayode's photography as 'poor imitations'.

Fani-Kayode's intention within his photography, as Mark Sealy puts forward, was to bring forth a 'spiritual dimension', problematising notions of 'reality' by returning to his ancestral Yorùbá heritage and traditions. Although Fani-Kayode's approach was 'relational' and 'multilingual', in Glissant's phrasing, like the Abiku, it was also paradoxical and spoke to, for and about the other, as well as the self. The Abiku, and other African motifs in his art, enabled Fani-Kayode, as Steven Nelson suggests, to 'play with the language of representation, particularly in its intersection with the black body'.

Through the Abiku (Born to Die) series, he articulates exile and displacement, which, for many like him who have experienced it, long for a homecoming which may never materialise and therefore can only be imagined – half of his being forever belonging elsewhere. Because of this, his photography, along with that of others whose practice challenged Western hegemony and simple categorisation of identity, marked a paradigm shift within (post)modern visual art criticism and scholarship.

In asking his audience and critics to see the world through his lens and language inherent in his practice, Fani-Kayode personifies Kobena Mercer's call for a reappraisal and reinterpretation of Black British arts practice, its objects and materials.

Ian Sergeant, curator-researcher

This content was published as part of the Transforming Collections project