Few artists have balanced abstraction and figuration as effortlessly as Roger Hilton (1911–1975). His paintings are unpredictable, raw, and filled with restless energy, qualities that make him one of the most compelling yet underrated figures in British post-war art.

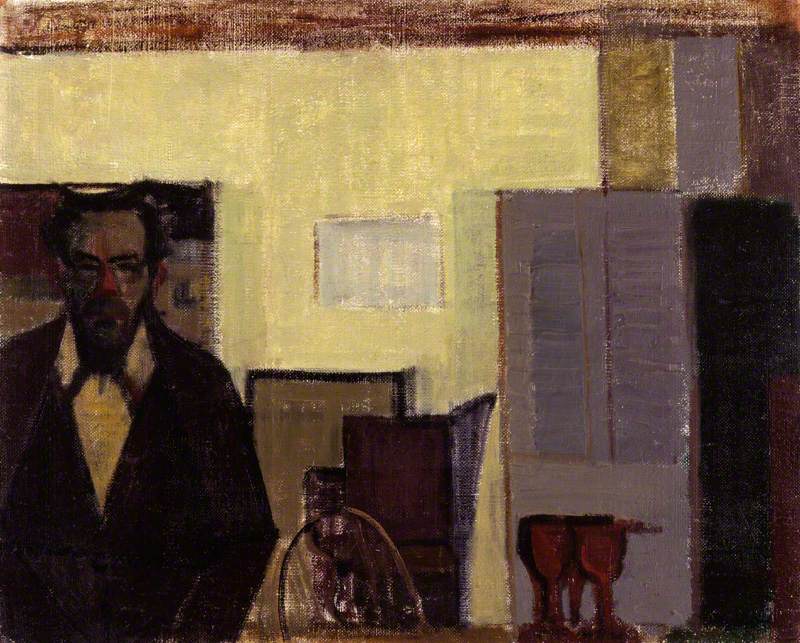

Born in Northwood, now part of the London Borough of Hillingdon, Hilton studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London from 1929 to 1931. Eager to refine his artistic approach, he moved to Paris in the 1930s and studied at the Académie Ranson where he was mentored by Roger Bissière, a key figure in the Nouvelle École de Paris.

However, his artistic trajectory was abruptly halted by the outbreak of the Second World War, during which he served in the commandos. After the war, he resumed his artistic career, teaching at the Central School of Art and Design in London before fully committing to his artistic practice.

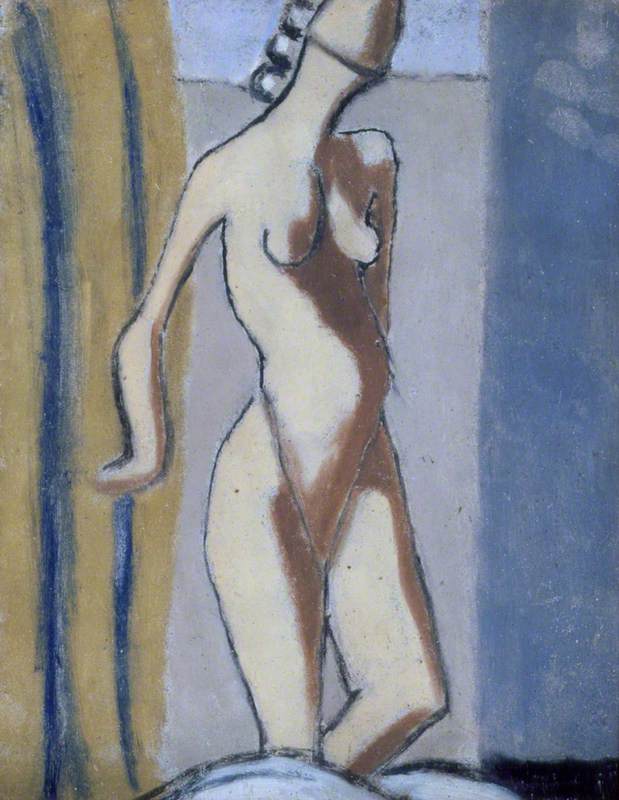

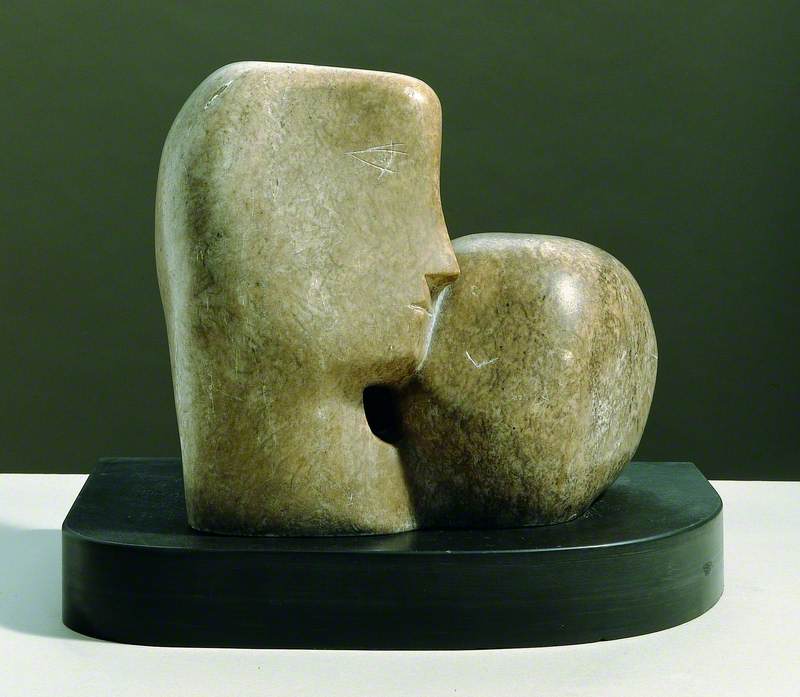

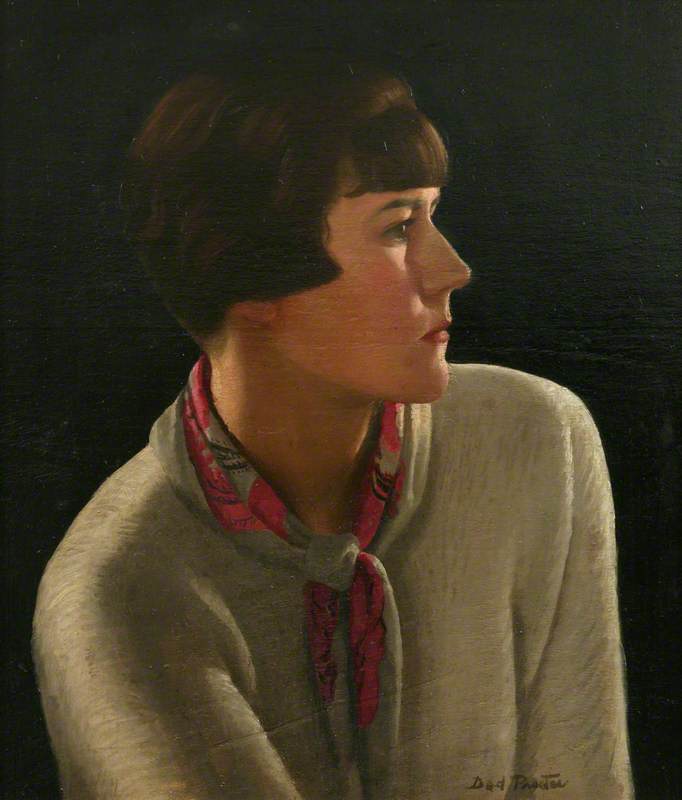

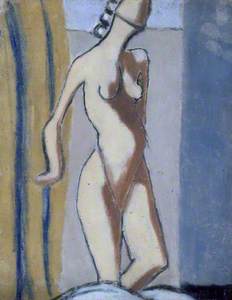

Hilton's artistic evolution was not linear but progressed through multiple phases, oscillating between abstraction and figuration, yet always marked by a gestural and expressive energy. His very early works in the 1930s leaned towards realism, featuring portrait and figurative compositions, such as Ghislaine and Grey Nude (1935).

While in Paris, he was profoundly influenced by the burgeoning abstract movements, particularly the works of Piet Mondrian and the European avant-garde, which laid the foundation for his post-war abstraction.

Upon returning to England after the war, Hilton emerged as a leading figure in British abstraction during the 1950s. His early abstract works, such as Composition 1950–1951 and Composition II (1951), reveal a strong French influence, particularly from Tachisme and Bissière's techniques.

Composition II (1951) adopts a dynamic abstraction, blending geometric and organic shapes without rigid symmetry. The artist plays with balance, alternating between solid colour fields and gestural strokes, conveying a fluid and spontaneous movement. There is a strong use of black, with visible brushstrokes and sometimes blurred or irregular contours.

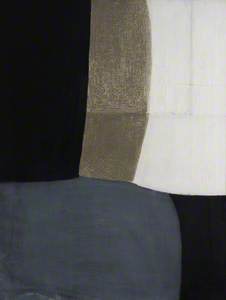

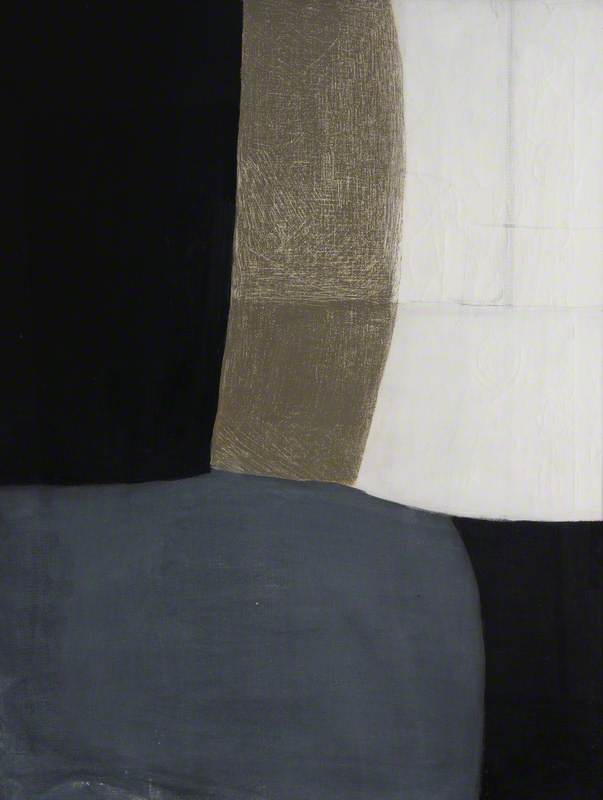

By 1953, Hilton's style evolved towards a more structured abstraction, characterised by textured colour fields, simplified forms, and a restricted palette of primary colours, black, and white. Works such as Untitled (1953) illustrate this transition.

From 1955 onwards, Hilton progressively reintegrated the human figure into his compositions in a more suggestive manner. Works such as Figure (1955) and October '56 (Brown, Black and White) illustrate this movement towards a gestural and fragmented figuration, where the human presence is implicit rather than directly represented.

However, pure abstraction remained present in his work, as seen in October 1955 (Calm, Black, Grey, Brown and White).

October, 1955 Calm (Black, Grey, Brown and White)

1955

Roger Hilton (1911–1975)

Hilton was deeply committed to the formal and expressive aspects of painting – colour, space, material – while insisting on the necessity of a subject, particularly the human figure. In a letter to artist Terry Frost in 1955, he wrote: 'It is disconcerting not to know whether my next exhibition will consist of chaste abstractions or violent figurations, but it will inevitably be one or the other. If abstract, they will be lightning-fast, demonic, tragic, expressionist, violent, unbridled, and destructive.'

By the mid-1950s, Hilton had aligned himself with the St Ives School, a collective of artists based in Cornwall, which included Frost, Patrick Heron and Peter Lanyon. They weren't interested in rigid categories but instead sought to push the boundaries of pictorial language by blending abstraction with figuration.

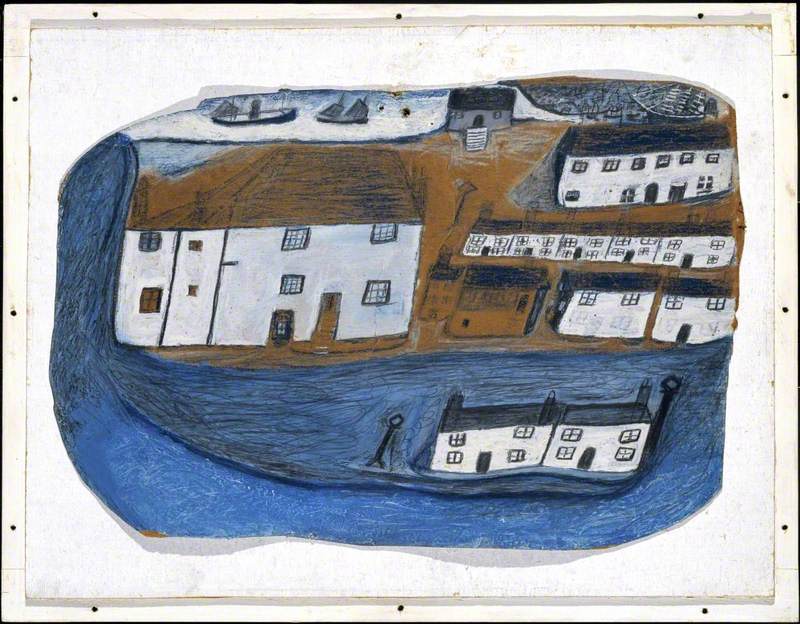

As Hilton began making visits to St Ives in 1956 (he moved to Cornwall permanently in 1965), elements of the landscape – beaches, boats, rocks, and water – started surfacing in his work, as seen in Black and Brown (c.1958). It was during this period, from the late 1950s and through the 1960s, that Hilton's reputation soared. He won the John Moores Painting Prize in 1963 and in 1964 he exhibited at the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Black and Brown, painted after his stays in Newlyn, oscillates between abstraction and figurative suggestion. At first glance, it appears to consist solely of abstract forms and textures, but upon closer inspection, it subtly evokes a harbour landscape: a dark line suggests the hull of a boat, while brown and ochre tones hint at rocks and land.

In 1961, Hilton explicitly rejected pure abstraction in the introduction to his exhibition at Galerie Charles Lienhard in Zurich. He wrote: 'Abstraction in itself is nothing. It is only a step towards a new figuration, one that is truer... For an abstract painter, there are only two possible outcomes: either he abandons painting for architecture, or he reinvents figuration.'

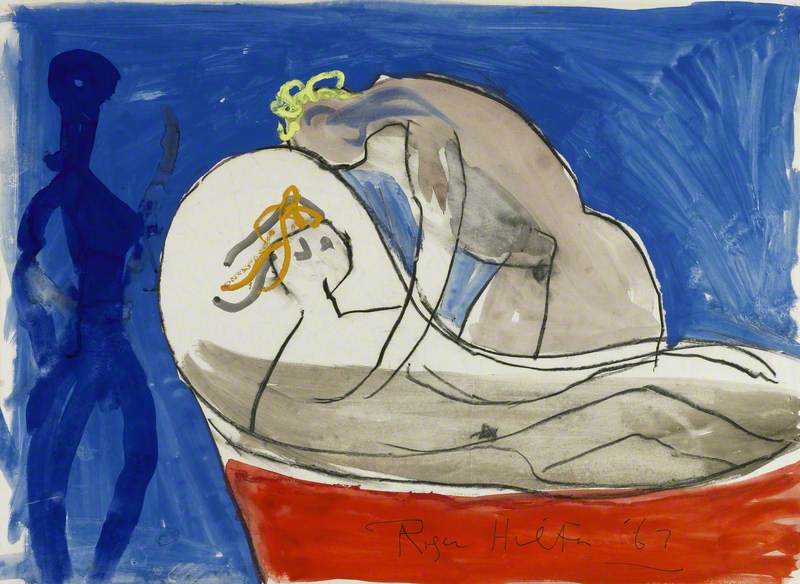

By the late 1960s, Hilton had moved away from pure abstraction and turned to figuration, but in a raw, unpolished style. His figures became simplified – quick, almost childlike sketches with thick lines, little detail, and no sense of depth or perspective. There was no attempt at realism, just a direct, almost urgent expression of form.

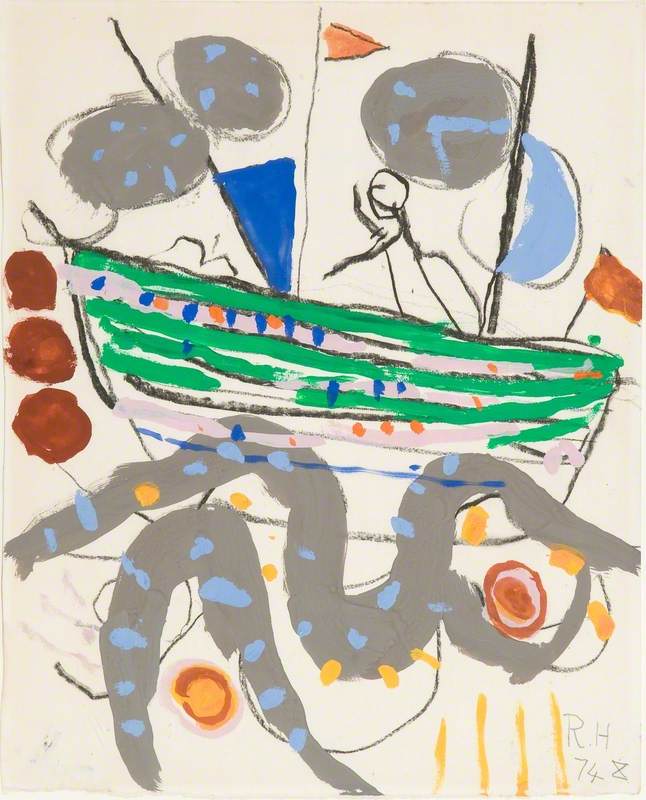

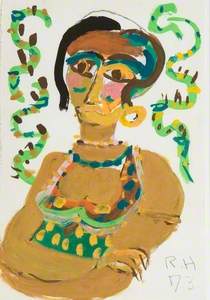

Works such as Boat (1974) and Bust of a Woman with Serpents (1973) illustrate this shift. In Boat, Hilton depicts a stylised vessel, evoking the simple forms and bright colours often associated with naive art. The use of thick lines and contrasting tones lends the work a dynamic energy.

This representation can be interpreted as a reference to the maritime landscapes of Cornwall, a region dear to the artist, while also reflecting a more playful and spontaneous approach to composition. The work reveals Hilton's ability to distill complex scenes into essential forms while retaining emotional depth.

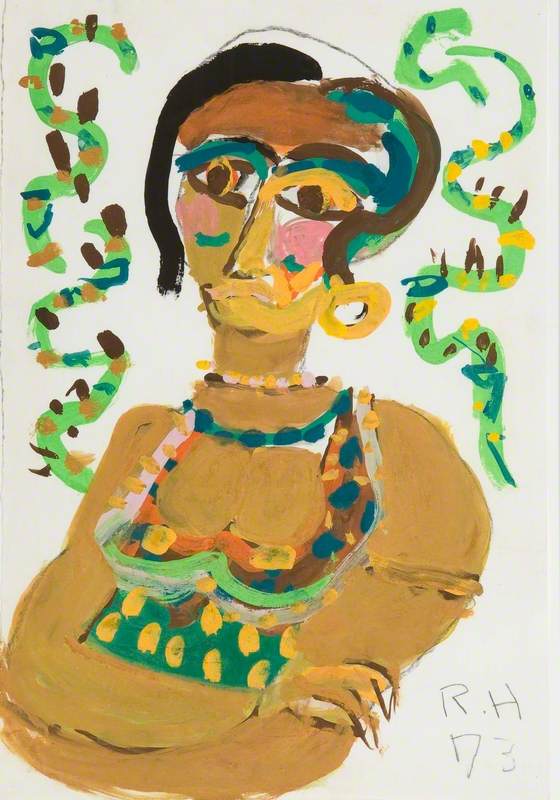

Bust of a Woman with Serpents, drawn in charcoal and gouache, is part of a series Hilton created after becoming bedridden. The woman's face is roughly outlined, staring out with an eerie stillness, while snakes coil around her, twisting the image into something almost mythological.

There's a rawness to this work – an urgency in the lines, a tension in the composition. It feels less like a carefully planned piece and more like an immediate, visceral response to whatever was on his mind at that moment.

During the final two years of his life, confined to bed and in declining health – partly the result of a lifetime spent smoking and drinking – Hilton turned to an even more personal form of expression: Night Letters. This series of more than 1,000 gouaches and illustrated notes to his wife, Rose, also an artist, whom he married in 1965, became his final artistic outpouring. They are part love letters, part absurdist humour, part unfiltered reflection – often playful, sometimes crude, but always full of life.

Hilton may not be as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, but his influence is undeniable. David Hockney acknowledged Hilton's impact on his early abstractions, and artists such as Brett Whiteley were inspired by his raw, expressive approach.

While his work fell out of favour in the 1970s with the rise of conceptual art, his legacy was rediscovered in the 1980s, notably during the 1981 exhibition 'New Spirit in Painting', which brought expressive figurative painting back into the spotlight. His ability to merge abstraction with figuration, to capture human experience in its most unfiltered form, ensures that his work remains as vital today as it was in his lifetime.

So if you haven't explored Hilton's paintings before, now's the time. His work is a masterclass in controlled chaos – a testament to the power of painting at its most direct and instinctive.

Louise Jacquier, art historian

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation