From the armour of Greek gods to the space suits of astronauts, from active service on the battlefield to firefighting, cycling, cricket and air travel, the helmet is found everywhere. A symbol of human presence and physical fragility, the helmet instantly conveys a sense of loss when empty. No wonder, then, that this headgear recurs in stories, legends and artworks, embodying ideas of power, heroism, inventiveness – and pathos.

In ancient Greek mythology, magical powers were often ascribed to battle attire, including the helmet. The cap of invisibility worn by Hades, god of the dead, and by Perseus, when he slays Medusa, is one example, illustrated on vessels at the British Museum. Also on display are actual bronze helmets in the Corinthian and Thracian style that were worn in battle or used as votive offerings, dated between 700 and 400 BC.

Bronze helmet of Corinthian type

c.510 BC, Greek, bronze

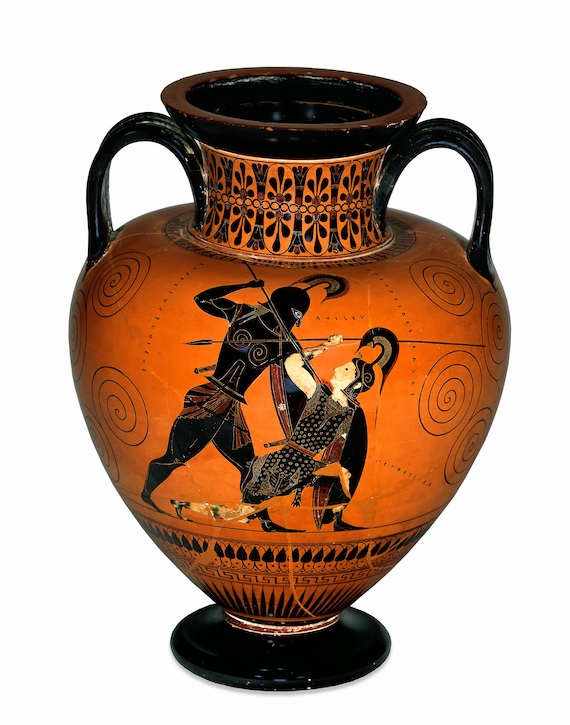

In this black-figured amphora from Attica in Greece, the two warriors locked in mortal combat are Achilles (left) and Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons.

The Exekias Amphora

c.540–c.530 BC, Greek, black-figured pottery amphora by Exekias (fl. 545–525 BC)

They both wear high-crested helmets, but Achilles – half-man, half-god – is transformed into an implacable killing machine by a helmet that conceals his face and identity, whereas Penthesilea, forced down onto one knee, has her serpent-headed visor pushed back, exposing her features. As she stares up at her attacker, Achilles plunges his spear into her throat and blood comes gushing out. Legend has it that when their eyes meet, they fall in love – too late.

British artist Michael Ayrton created a number of works inspired by ancient Greece. His 1957 bronze, Talos, Armed Head II, references the mythical guardian of Crete, a monstrous man made of bronze who wades around the island hurling boulders at approaching intruders.

In appearance, Talos, Armed Head II is part-bust, part-archaeological find; the helmet is topped by what looks like a broken axe blade that blends seamlessly into the crown. Two ear flaps hang down, with a tail-wedge shape at the rear, and the sightless face with its fractured surface recalls earlier bronze sculptures by Futurist and Cubist artists, such as Umberto Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), and Joseph Csaky's Tête (Cubist portrait) from 1914.

Alongside ancient Greek examples, the British Museum also holds two extremely rare and significant helmets from ancient Britain: the horned Waterloo Helmet belonging to the Iron Age, and the Sutton Hoo Helmet, worn by an unidentified Anglo-Saxon warrior.

The Waterloo Helmet is unlikely to have been used in battle due to the thinness of its metal and may have been worn in a ceremony, or placed on the wooden statue of a Celtic deity or a votive offering to the gods.

The Sutton Hoo helmet, which was found in pieces and has undergone extensive reconstruction, is an important symbol of the early medieval period. You can find out more about it from one of the Museum's curators in this video.

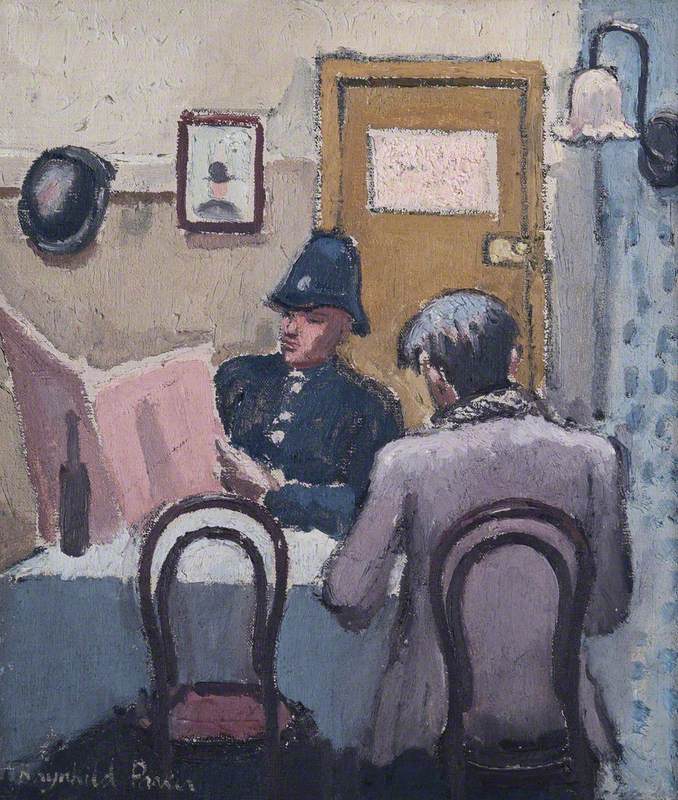

Closer to our own time are the steel 'Brodie' helmets of the First World War at the Imperial War Museum in London, depicted here in a 1919 work by Colin Gill.

The mechanisation of combat in 1914 – the use of artillery, tanks and machine guns – and the development of trench warfare resulted in huge losses of life. Many injuries suffered by soldiers were to the head. In 1915, the 'Brodie' steel helmet ('shrapnel helmet') was patented by John L. Brodie for British soldiers. It was distinctly different from the superior German Stahlhelm (1916) which offered more protection.

Both types were light, comfortable to wear and easily mass-produced. Their differing shapes meant that each side was distinguishable on the battlefield.

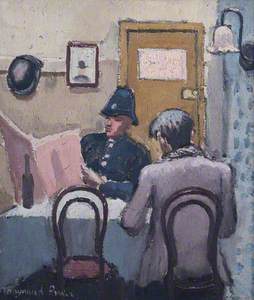

In Gill's painting The Captive (1918), the British 'Brodie' and the German Stahlhelm do more than identify each side: they emphasise the emotional states of the soldiers.

The British captor is exhausted and his eyes droop beneath his tilted hat, while the German prisoner is hunched down, his watchful eyes shadowed by the helmet clamped on his head. Is he resigned to his fate, or calculating escape?

Although the troops on the march in A French Highway (1918) by John Nash wear identical headgear and khaki uniforms, their stylised features – described with the greatest economy – turn them into individuals.

The soldier closest to us is speaking to a sullen companion, as three others trudge behind in silence. Two French officers trot past on horseback, their midnight blue cloaks giving way to the greyness of the day. We can imagine the monotony of the march and military duties of these soldiers; they are bored numbed men whose lives are tamped down by their 'battle bowlers'.

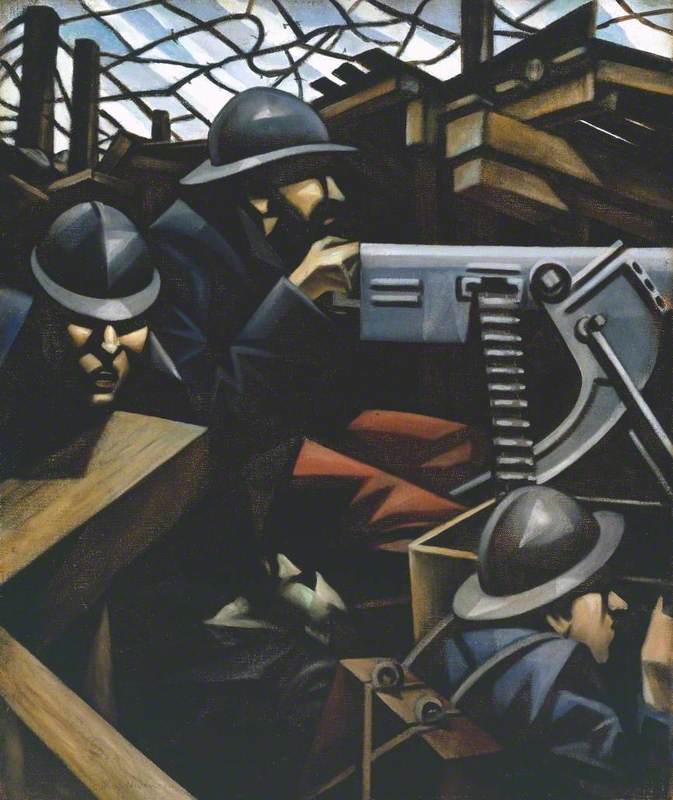

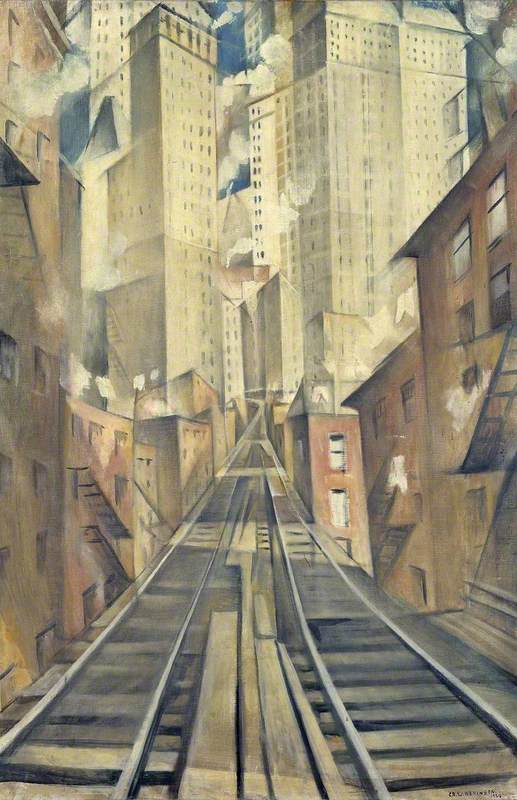

La Mitrailleuse (The Machine Gun) was painted in 1915 by C. R. W. Nevinson, whose interest in the work of the Italian Futurists and the French Cubists is clear here.

The anonymous gunner is depicted as an extension of the machine gun he operates: everything is hard and angular; the men are machine-like in their faceted gunmetal grey helmets, sharp enough to slice, while the gun itself becomes the gaping maw of some robotic beast.

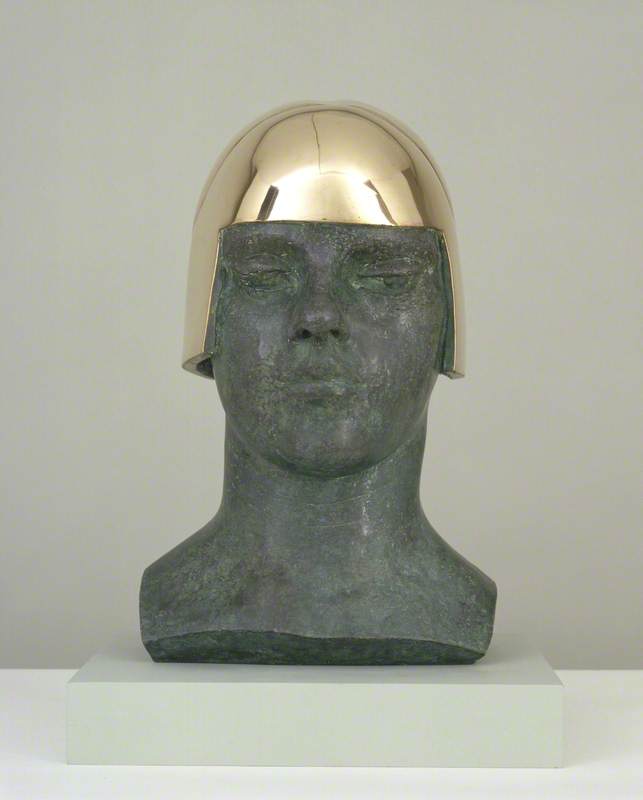

This portrait bust by Jacob Epstein from 1915 is of Iris Beerbohm Tree, a young poet and actor, who reputedly cut off her hair and left it on a train.

Here, she is portrayed with a bright burnished bob – a simplified abstracted form, a helmet – while the features of her face are modelled in a softer, more realistic style.

Made almost 70 years later, yet displaying a similar handling of patination, Gareth Fisher's 1983 sculpture, More Helmet than Head, shows the smooth shape of what looks like a pilot's helmet, enclosing the pitted, jagged ruin of a face, where only the nose is unbroken.

The previous year, in 1982, the UK had been engaged in the Falklands War, which entailed air warfare between the British and Argentine forces. In this instance, the flight helmet is an important part of military air force kit, offering noise protection and a means of communication with crew and control stations on the ground and even a sensory interpretation of the battlefield.

In 2019, the Wallace Collection in London organised an exhibition juxtaposing medieval and Renaissance helmets from its armoury with the Helmet Head bronzes of Henry Moore.

In 1971, the sculptor declared, 'The helmets in the medieval armour section of the Wallace Collection in London have always fascinated me. They have a purity of metal and a strength, outwardly; yet within, they convey an enclosedness, a quality of protection. These are the things I want to capture in my own variations on the theme.'

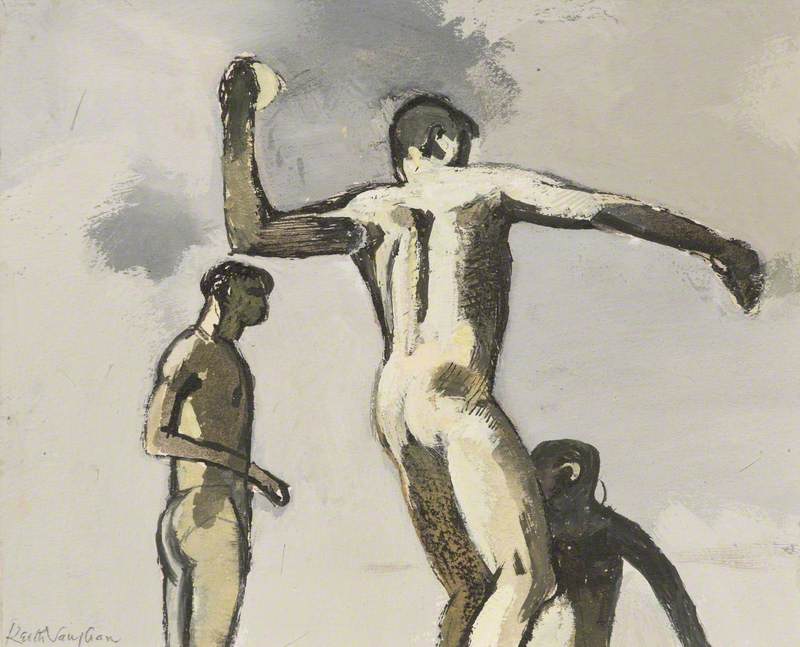

Following his service as a machine gunner in the First World War (when he wore the 'Brodie'), Moore had visited the Wallace Collection as a student and created his first helmet head on the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War. A steady production of helmet heads ensued in the unstable 1950s, when Moore continued to explore the theme of forms inside forms, mother and child motifs, and absence, expressed in metal shells enclosing a void.

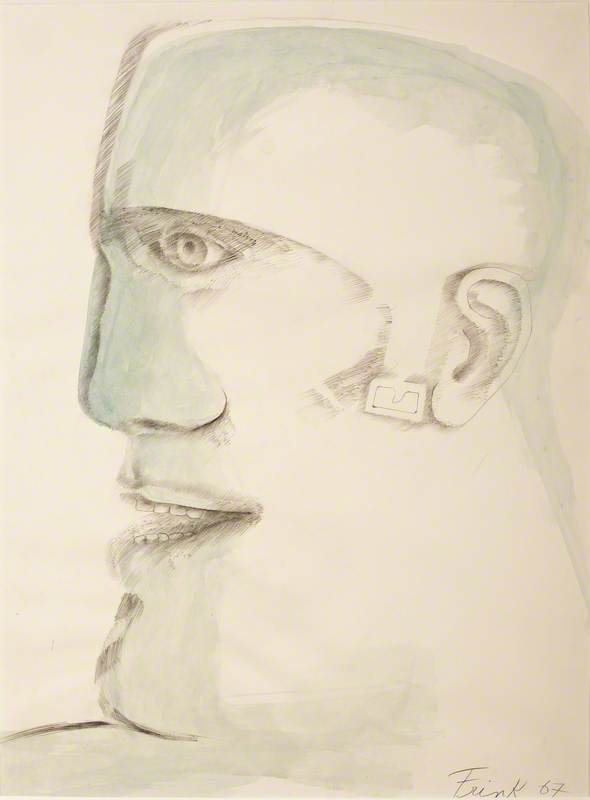

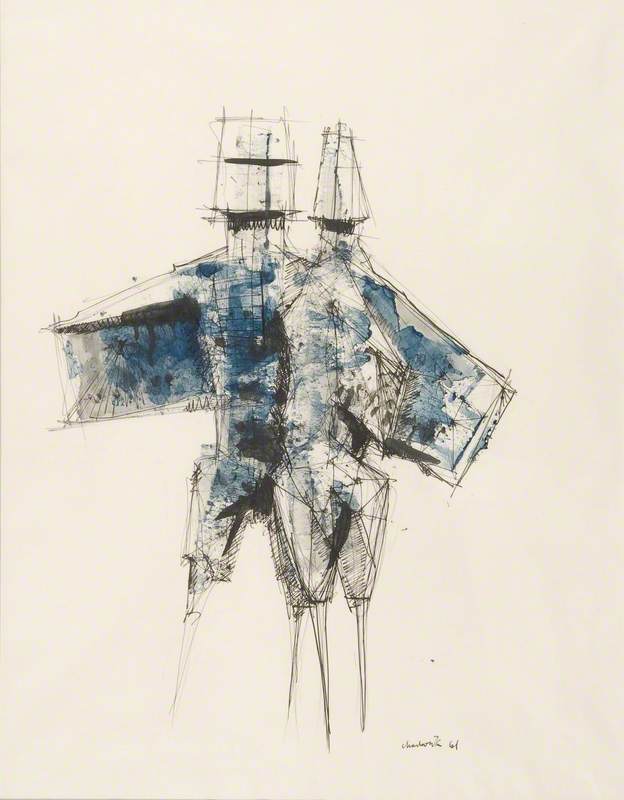

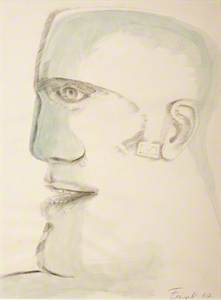

From 1966, Elisabeth Frink began a series of drawings depicting male heads, often wearing helmets.

Describing these works, art historian Edward Lucie-Smith described them as having 'enormous chins, tiny ears and low foreheads, so that the helmet – a low, quasi-medieval affair – comes right down over the brow... One aspect of these heads […] is the fashion in which Frink delineated mouths and teeth. In almost all cases the lips […] do not entirely cover the serried rows of teeth – a feature which gives these warriors a peculiarly predatory air…'

In the drawing here, however, the head with its buckled cap, open eyes and smiling mouth looks rather cheerful and comic, more bather than military man.

It's worth mentioning that Frink's father was a soldier at Dunkirk during the Second World War, and the family lived near an airfield in Suffolk while the artist was growing up. She later created a series of Birdmen and Goggle Heads artworks in response to conflicts such as the Algerian War (1954–1962) and the henchmen involved in it.

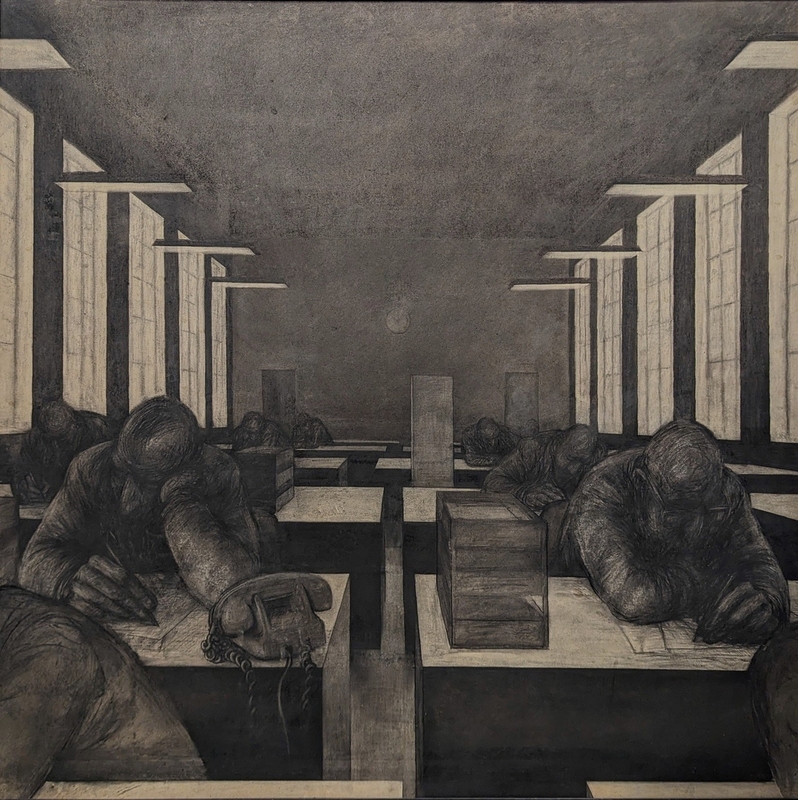

Many artists have also turned to the subject of working miners in hard hats equipped with lamps. In 1941, Henry Moore was commissioned by the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC) to record coalminers at Wheldale Colliery where his father had been a pit manager. Moore descended the mines and drew from life, later developing the initial sketches into finished drawings. The hard hats in Pit Boys at Pithead (1942), for example, are not an evocation of power but serve to dignify and identify the occupation of these men.

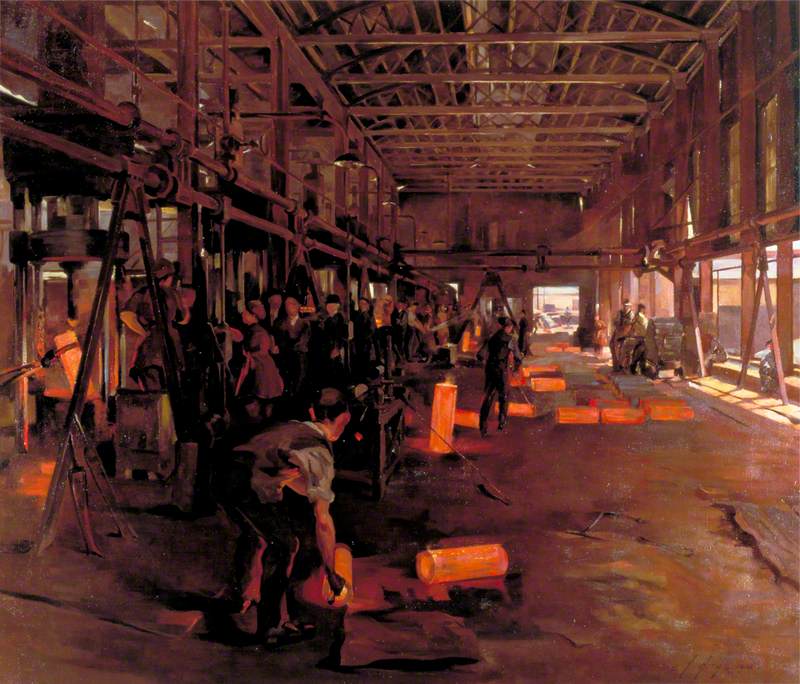

By contrast, Oliver Kilbourn was a working miner in Ashington, Northumberland. In 1934, he enrolled in an art appreciation group run by the Workers Educational Association under the guidance of Robert Lyon. The classes eventually evolved into a painting collective, focused on capturing the miners' lives and experiences.

Kilbourn's painting Coal-Face Drawers (1950) describes the task of removing the pit props and roof supports from the coal face of an exhausted mine, which had been one of the artist's employments. Labouring in a cramped low shaft deep in the earth, the miners strain in claustrophobic conditions, the only source of light coming from their helmets.

John Cobb's Head Case IV from 1978 is made from articulated wooden segments fanning out to form a carapace like a cicada shell.

Projecting from this is a frame almost resembling a muzzle, with a shield guard to protect or obstruct the eyes. The artist has built several sculptures using wooden pieces that reference the human body. This sculpture has a pleasing ambiguity: is it an armour of some sort or is it a mask to encumber and restrict? The visible joints of different grains slotted together contrast with the enclosed space in front.

In 1991, the Museum of Modern Art in New York held an exhibition 'Modern Masks and Helmets'. Associate curator Cara McCarty argued that the helmet provided 'a sculptural portrait of our technological society', differentiating between earlier individual styles and today's standardised forms from moulds. Yet as objects, we still feel emotional attachments to them and customise our helmets as we do our clothes.

Artist Grayson Perry is a keen cyclist (and motorcyclist) and can be found zooming around the hills of East Sussex dressed in pink, including his headgear. He contributed to a group show of cycling helmets repainted and refashioned by artists to be sold at auction in 2017 to raise funds for the brain injury charity Headway. Perry's interest in helmets is longstanding – in 1981, while still a student, he made the mock-Saxon Early English Motorcycle Helmet.

View this post on Instagram

Four years earlier, curator Ben Moore had shown a series of Star Wars Stormtrooper helmets decorated by well-known artists including Damien Hirst, Yinka Shonibare and Jake & Dinos Chapman, but when the physical helmets were digitised for sale as NFTs in an online auction, the project quickly soured, exposing empty-headed greed.

Whether ordinary or extraordinary, the helmet is both a subject and an object that will evolve and fascinate artists for years to come. Who knows how virtual reality headsets will look in fifty years' time?

Deborah Nash, freelance writer and journalist

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation