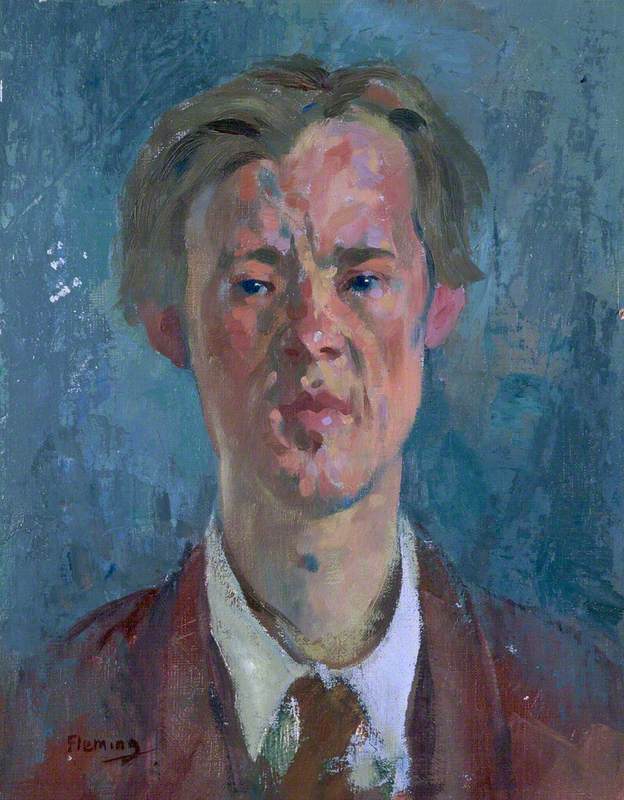

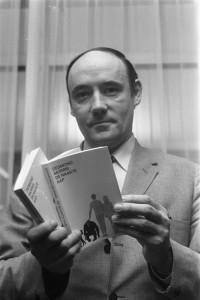

As part of his therapeutic approach, the English psychoanalyst Dr Alan McGlashan often encouraged patients to record their dreams during sessions. He spent much of his professional life practising in London, where he gained attention for his eclectic approach to psychiatry, heavily influenced by the theories of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung.

Dr McGlashan was inspired by Jung's work and made several trips to Zurich in the late 1930s for consultations with the renowned psychoanalyst.

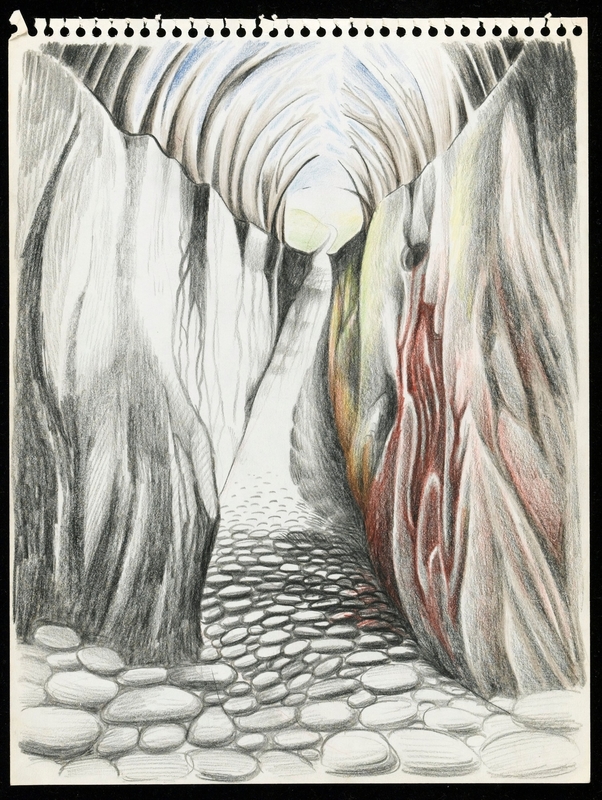

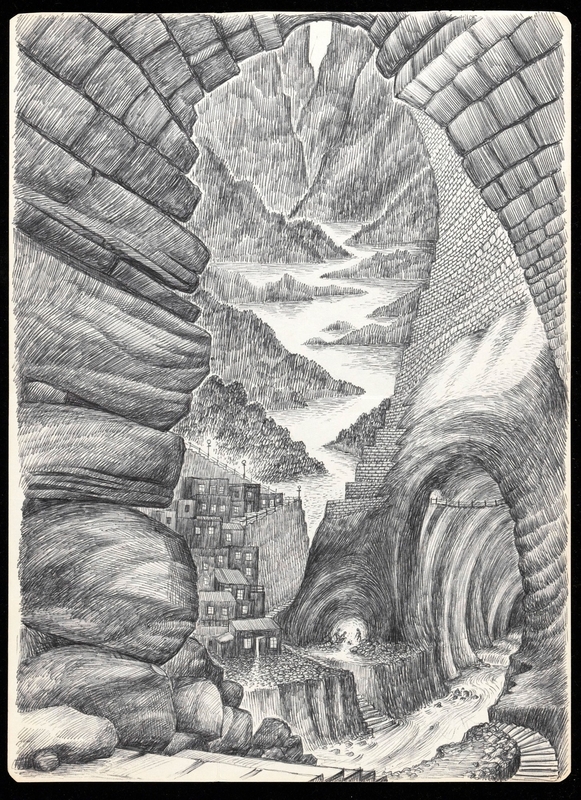

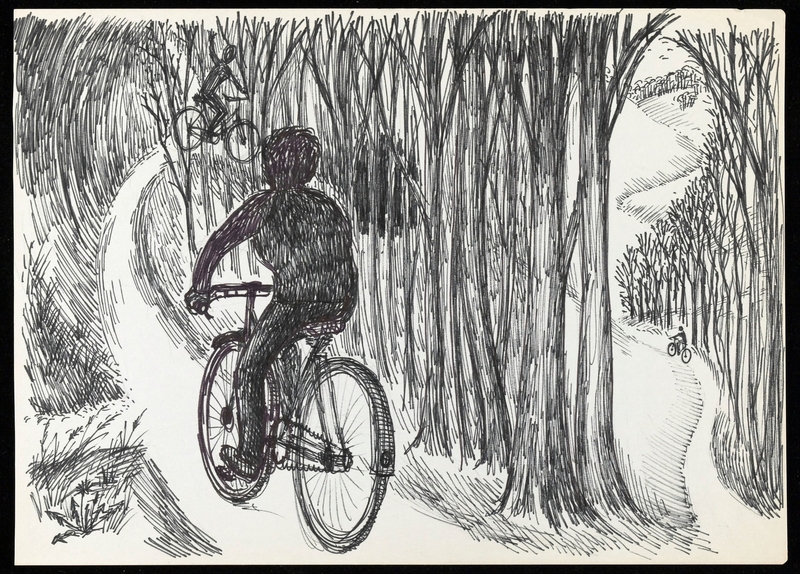

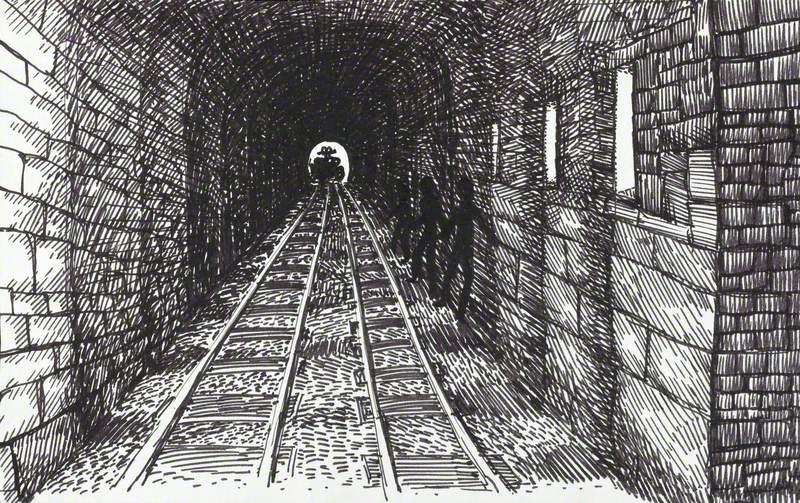

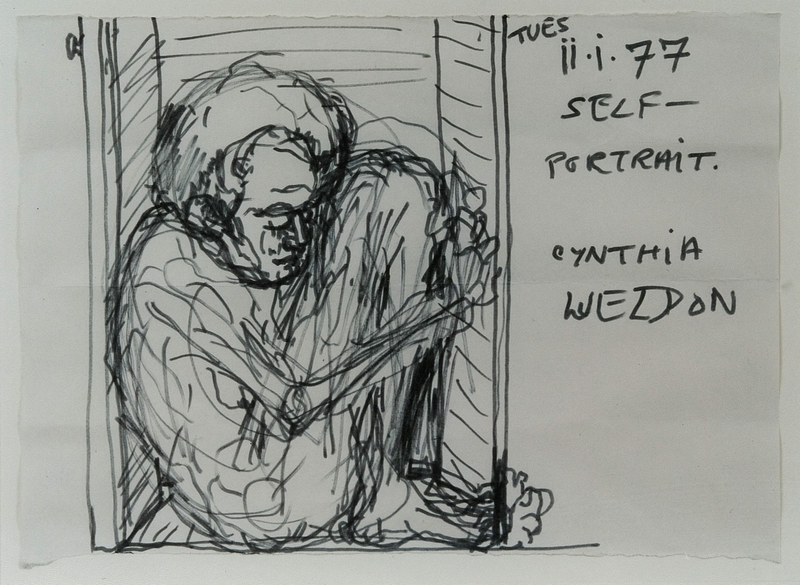

One of Dr McGlashan's patients, a professional artist, chose to express his dreams through drawings rather than words. Between 1967 and 1978, this patient – who signed their work as M. A. C. T. – created at least 20 drawings that are now held by the Wellcome Collection.

Jung developed his school of analytical psychology, now also known as Jungian psychology, in the early twentieth century. In the simplest of terms, Jungian psychology strives to unite the unconscious mind with the conscious. Its theories are driven by the concept of the human psyche, which Jung believed to be a self-regulating system comparable to the body, that is the totality of all psychic processes.

One method that Jung believed was key to understanding the psyche was analysing dreams. He considered dreams an avenue of communication between the unconscious and conscious mind. Analysing them could reveal unresolved emotional and mental challenges, which could lead to individuation – the process of discovering one's true self and purpose.

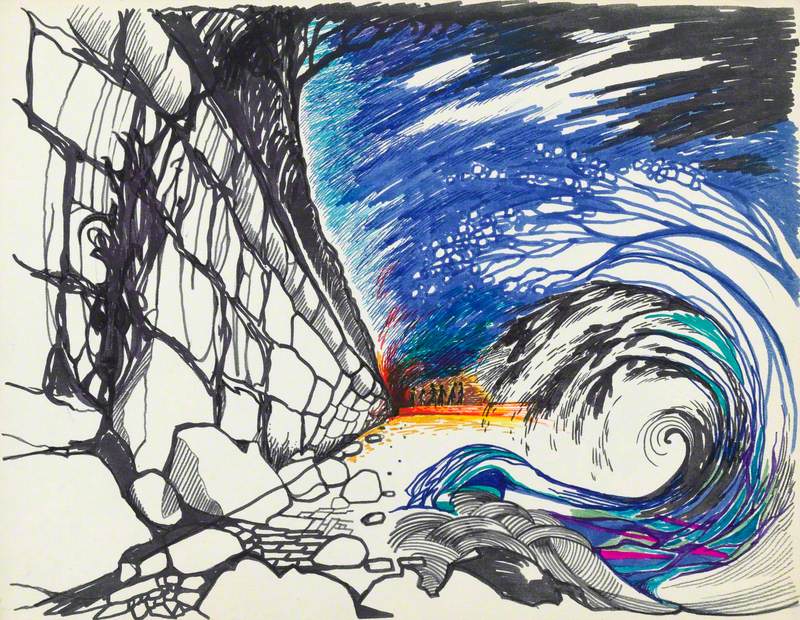

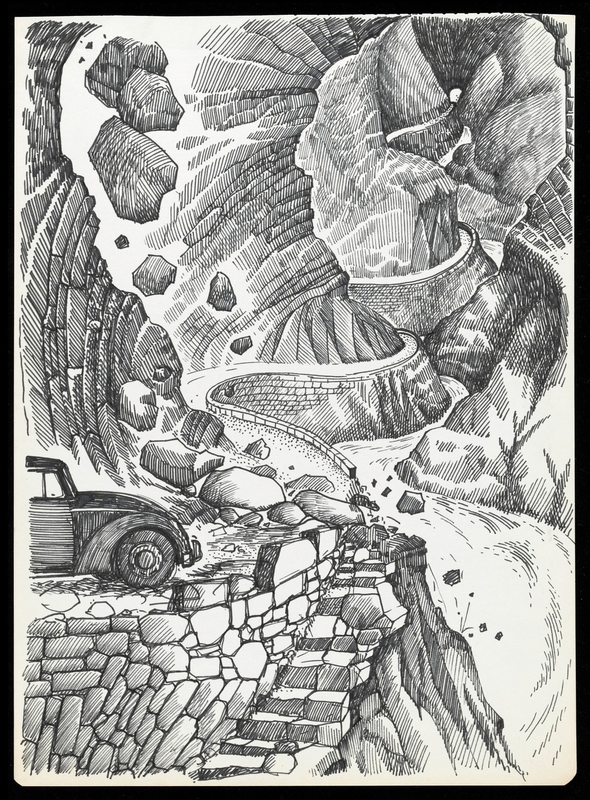

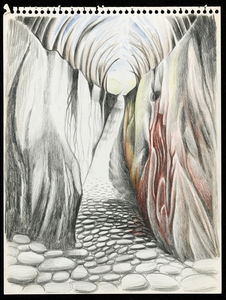

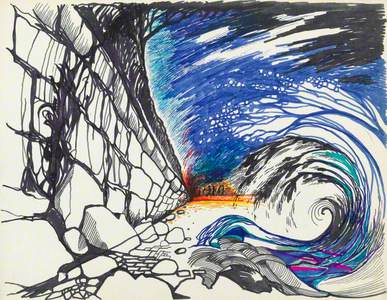

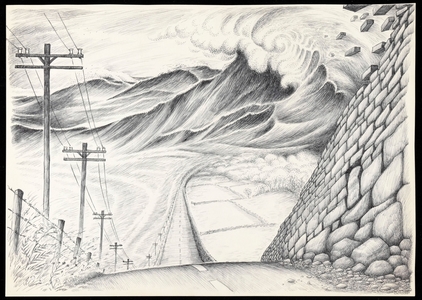

The Dream of a Patient in Jungian Analysis: a Volcanic Landscape by Moonlight

1967

M. A. C. T. (active 1967–1979)

As indicated by the title of M. A. C. T.'s collection of drawings, Dr McGlashan used Jung's dream theory to analyse his patient. Recording and analysing the dreams through drawings was time-consuming for both the practitioner and the patient, but served as an effective tool for Dr McGlashan to understand M. A. C. T.'s subconscious.

Dr McGlashan embraced Jung's advocacy for incorporating art into therapeutic practices, as Jung believed creativity was intrinsic to the psyche. Jung often encouraged patients to express themselves through art, viewing it as a powerful way to explore the inner self. Creating art could help unravel mysteries that the conscious mind struggled to understand.

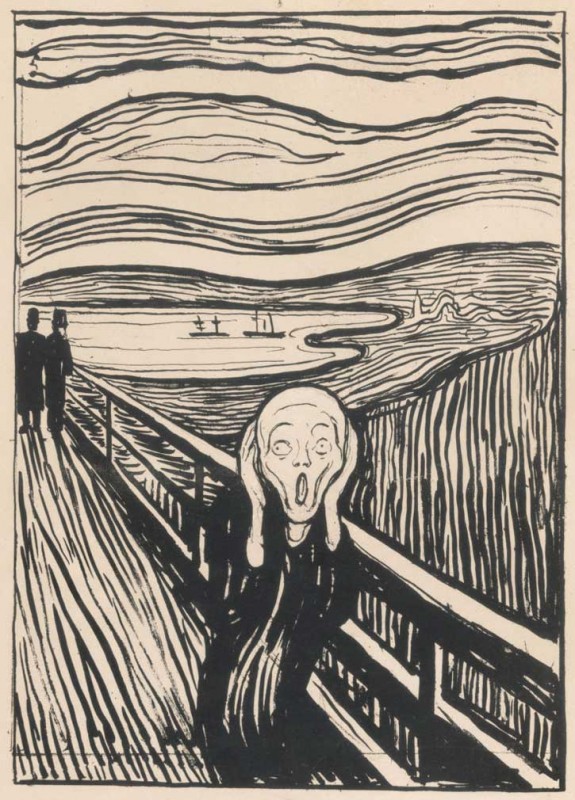

Jung didn't just promote his own theories – he practised them as well, with much of his work shaped by his introspection. Like M. A. C. T., Jung was an artist and often drew or painted his dreams for analysis. He advocated interpreting dreams symbolically rather than literally, believing that the symbols within dreams were powerful images that revealed deeper meanings.

In the book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, he stated: 'I took great care to try to understand every single image, every item of my psychic inventory, and to classify them scientifically – so far as this was possible – and, above all, to realise them in actual life. That is what we usually neglect to do...'

Jung identified symbols as having multiple meanings, with their significance being subjective and dependent on one's connection to the symbol, often influenced by cultural context. A closely related concept is the archetype. Unlike symbols, archetypes are universal themes represented through internal patterns that humans collectively experience. The purpose of archetypes is to guide and organise human behaviour, providing a framework to help us understand our world.

Identifying symbols and archetypes is a key aspect of Jungian dream analysis and likely played an important role in Dr McGlashan's approach to evaluating patients. Although we have limited information or context about M. A. C. T., we can still gain valuable insights by examining their drawings using the principles of Jungian dream analysis.

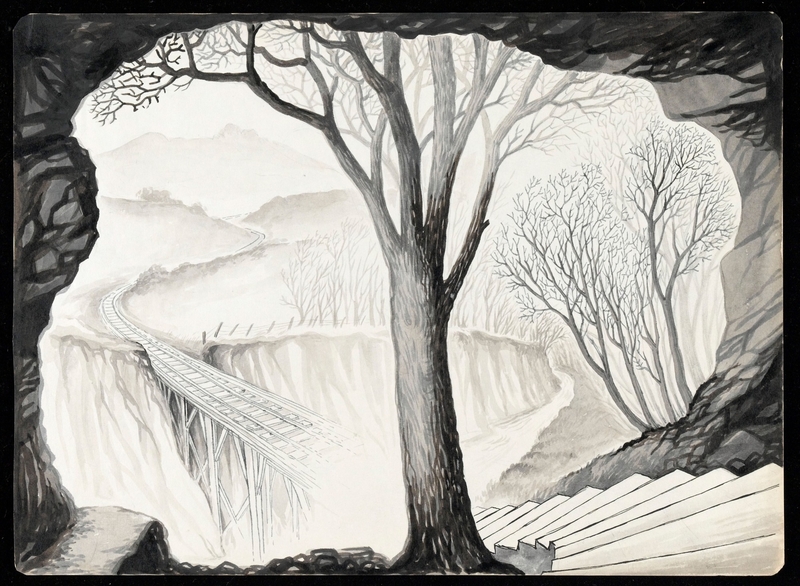

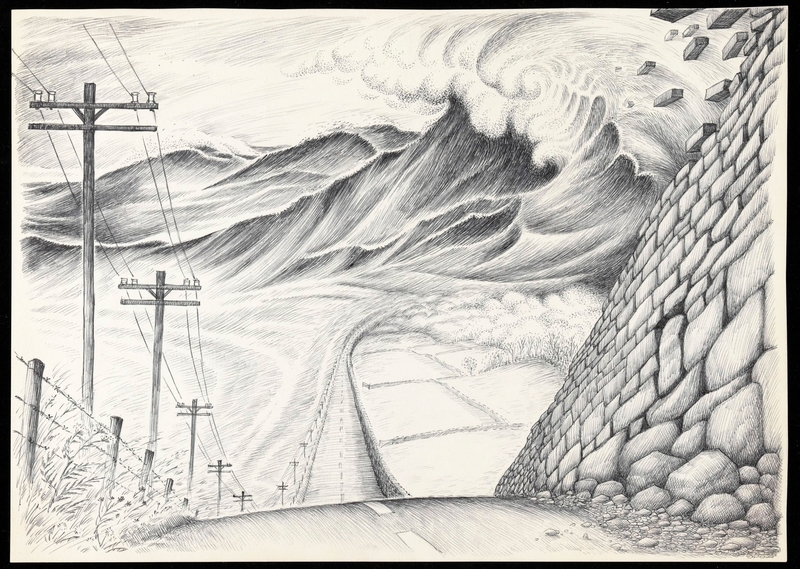

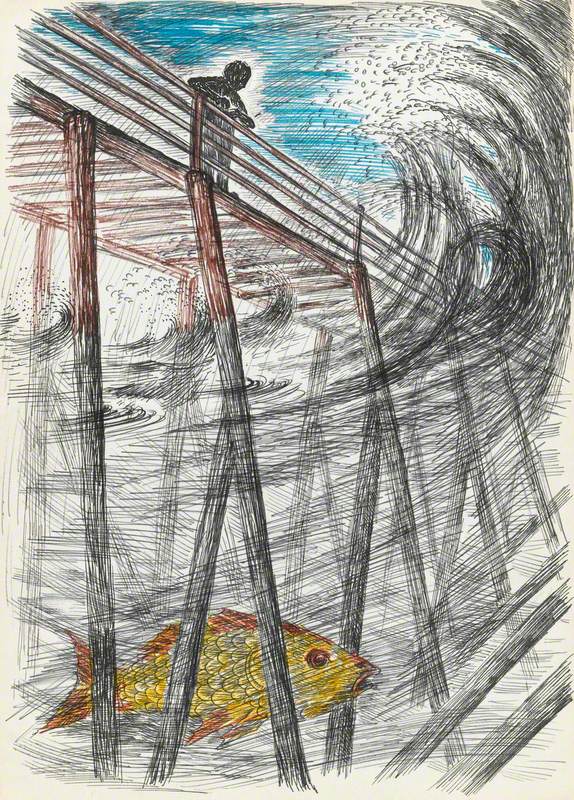

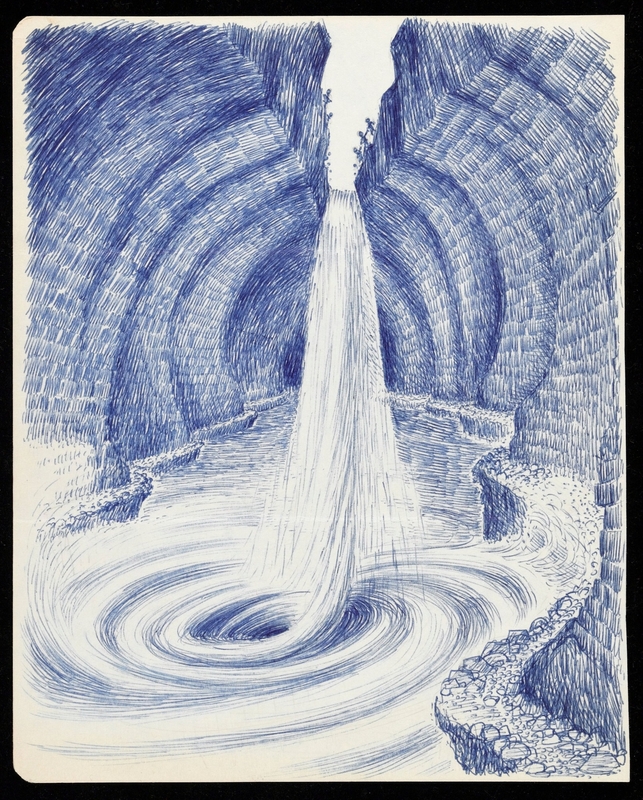

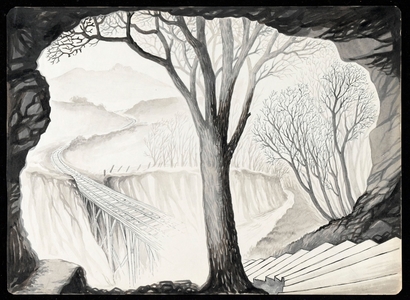

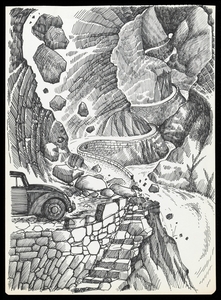

The collection centers around landscapes, with common elements such as trees, water, rocks and paths or bridges appearing frequently. For this brief analysis, we will focus on the element of water and the insights it may offer. Jungian psychology uses water as a symbol of the unconscious, representing depth, the unknown, and a powerful force. It also symbolises fluidity, reflecting the dynamic ebb and flow of the subconscious.

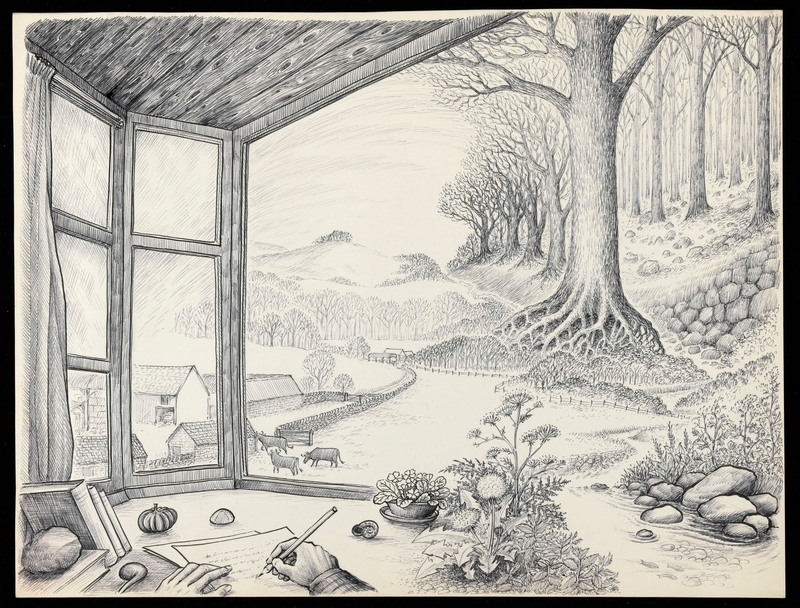

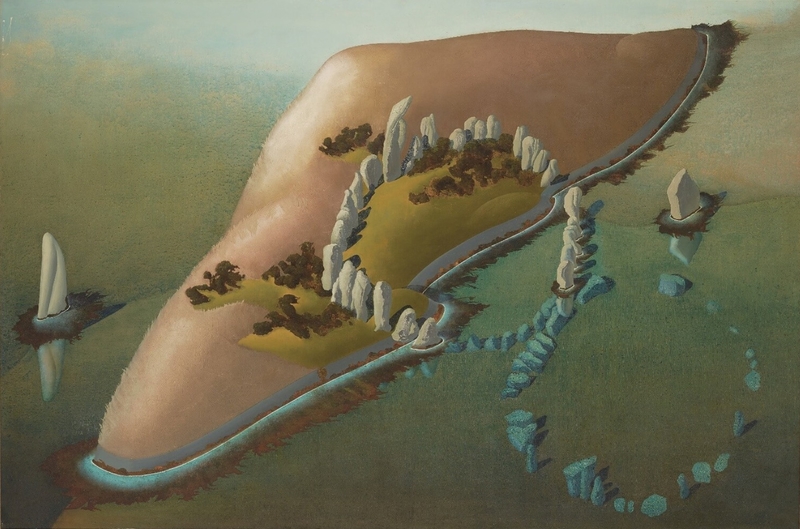

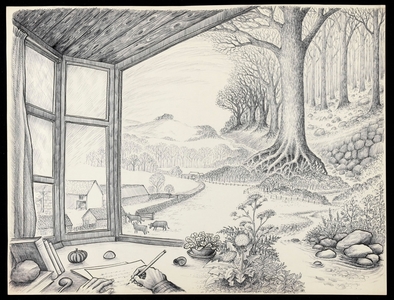

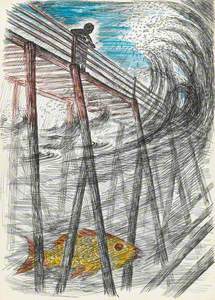

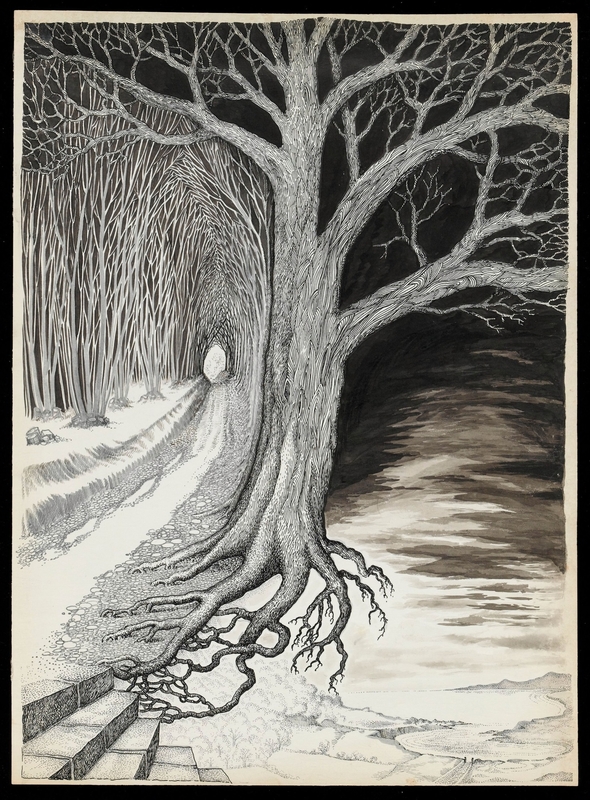

The Dream of a Patient in Jungian Analysis: Centre, a Tree; Left, a Path; Right, a Bay

1976

M. A. C. T. (active 1967–1979)

The drawings feature water in various forms, such as surging waves and a calm bay. This recurring theme suggests that M. A. C. T. may have been experiencing emotional turbulence, with significant highs and lows potentially stemming from the unconscious. The repeated depiction of water in different states symbolises the fluidity of emotion, making water an archetype in this collection. Its presence reflects a universal experience of emotional fluctuations.

Some drawings feature one or more figures observing a body of water, and we might assume that one of these figures represents the patient. This could suggest a moment when the patient was open to exploring their unconscious mind – such as in the image of a figure standing on a bridge, gazing down at the water with a goldfish. The figure observes the turbulent waters from the safety of the bridge.

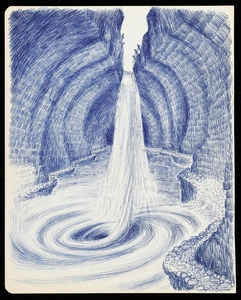

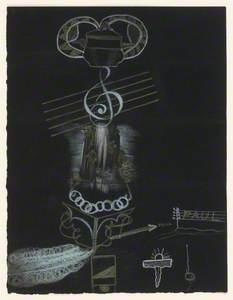

The drawing featuring figures gazing down at the rushing waterfall evokes a contrasting sense of reluctance and danger. Standing at the cliff's edge, they are confronted with the force of the water, mirroring the emotional risk of facing one's fears. The waterfall could symbolise the overwhelming emotional depths the patient may fear confronting. It's as if they are drawn to explore, yet hesitant to get swept away by what lies beneath.

One drawing stands out as the only one where the patient, or their alias, confronts water rather than observes it. The image shows a figure crossing a stream by stepping from log to log – a careful effort to avoid falling in while moving forward. The path may represent a new chapter in the patient's life, accessible only by navigating this challenge. The figure seems to avoid emotional depth, perhaps due to fear of confronting hidden trauma or subconscious anxieties.

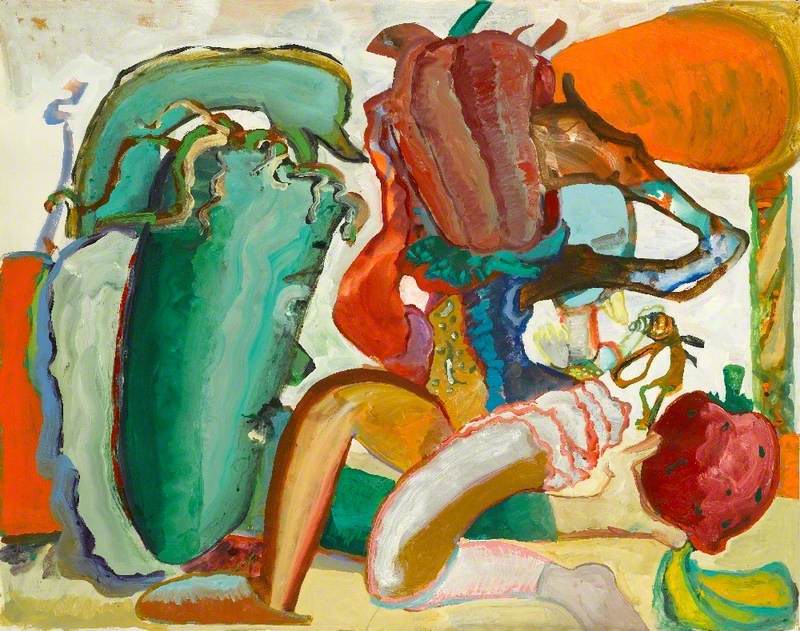

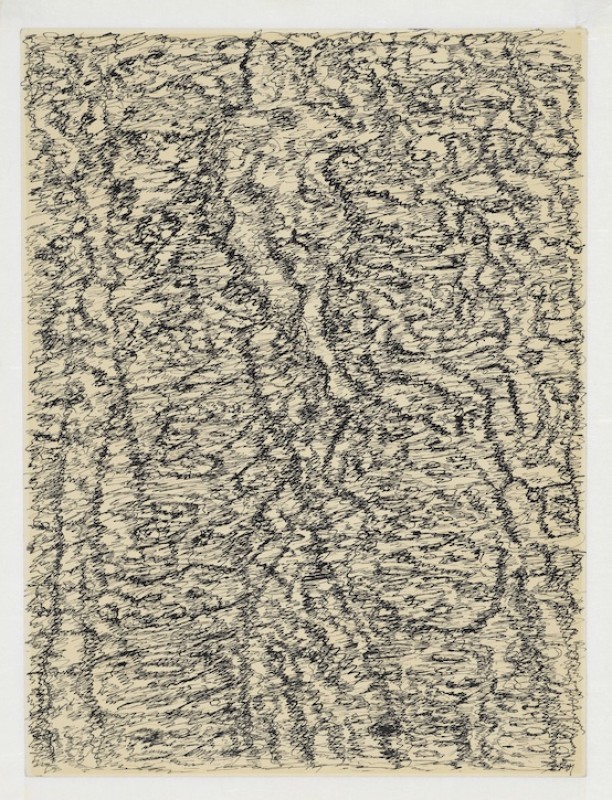

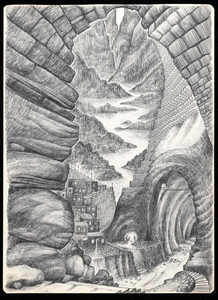

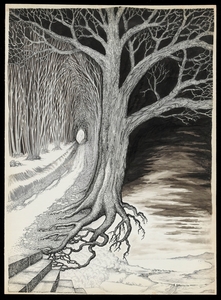

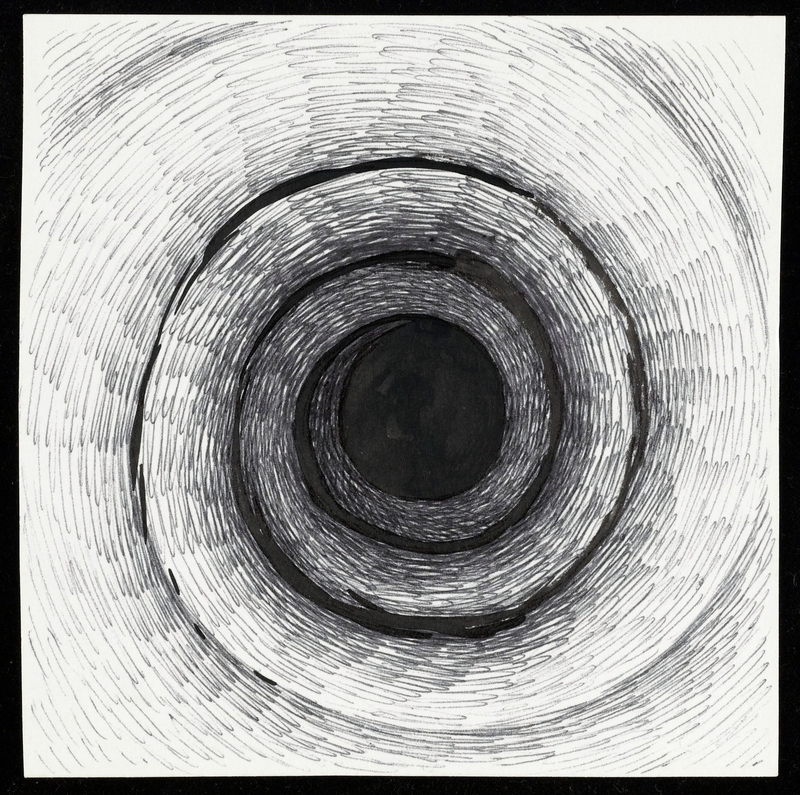

One drawing in the collection doesn't depict a scene: A Whorl with a Black Circle at the Centre, a geometric design made with pencil strokes and black ink. The spiral, starting with light strokes and gradually darkening, could symbolise internal turmoil or a descent into a black hole, often representing a difficult mental period or depressive episode.

The swirl might also connect to the image of figures peering down a waterfall, as a similar swirl appears there. However, without a chronological timeline of the drawings, it's difficult to determine if there's a direct correlation between the two swirl images.

The Dream of a Patient in Jungian Analysis: a Whorl with a Black Circle at the Centre

1970–1979

M. A. C. T. (active 1967–1979)

The observations above represent just a few possible conclusions drawn from M. A. C. T.'s drawings, with many other symbols and images to consider. These conclusions are speculative and offer potential insights into M. A. C. T.'s sessions, but they cannot be confirmed. Dr McGlashan would have analysed each drawing in detail, with connections and possible meanings emerging through talk therapy. Notably, the subjects remain consistent over the eleven years represented by these drawings, except for the black whorl image from 1978, near the collection's end.

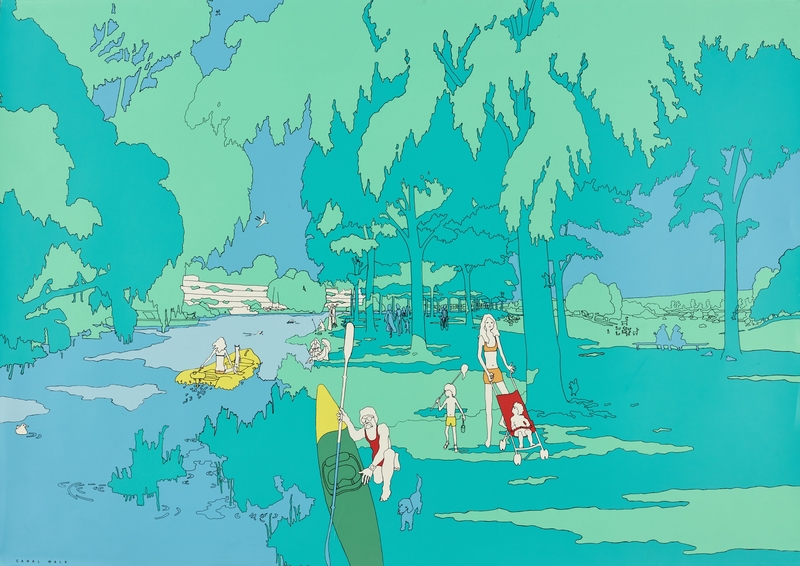

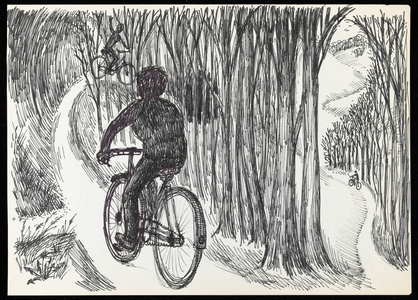

Jung's work had a significant influence that extended beyond the practices of psychoanalysts. The Surrealist movement, which focused on exploring the unconscious mind and dreams, drew on ideas similar to Jung's theories. This included the technique of automatic writing, which was also used by M. A. C. T. to record their dreams. Artists in the Surrealist movement were influenced by Jung's teachings as well as those of fellow psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. The artworks from this movement often used methods that tried to remove the control of the artist.

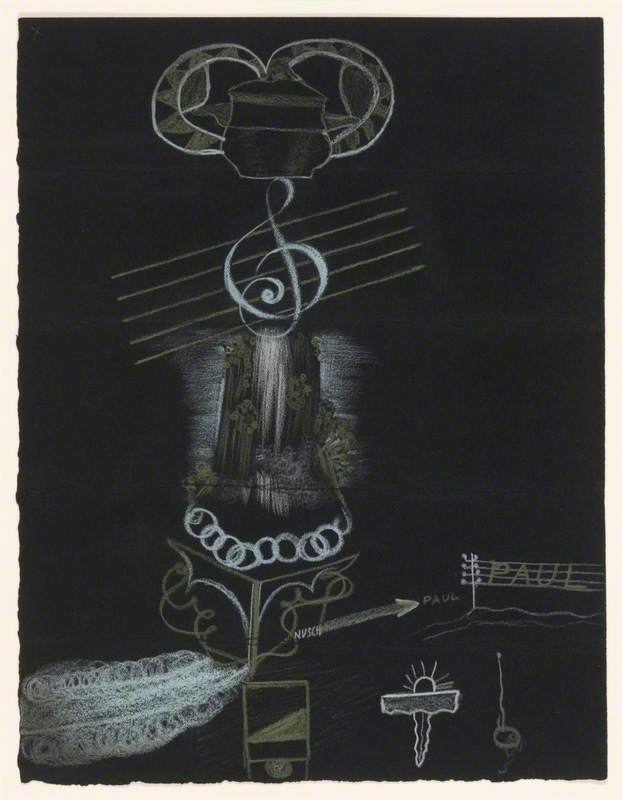

Exquisite Corpse (Cadavre Exquis)

c.1930

André Breton (1896–1966) and Nusch Éluard (1906–1945) and Valentine Hugo (1887–1968) and Paul Éluard (1895–1952)

Whether in formal psychoanalytic treatment, like M. A. C. T.'s or the creative expressions of Surrealist artists, Jung's teachings have a profound impact, guiding individuals to explore and heal their unconscious minds through art.

Cortney Ellis, writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Siri Erika Gullestad, 'Confronting the foreign. Surrealism and psychoanalysis in dialogue' in The Scandinavian Psychoanalytic Review, 45 (1), 2022, pp.24–34

James A. Hall, Jungian Dream Interpretation: A Handbook of Theory and Practice, Inner City Books, 1983

Robert Hinshaw, OBITUARY: Dr Alan McGlashan, The Independent, 1997

Harry T. Hunt, 'A collective unconscious reconsidered: Jung's archetypal imagination in the light of contemporary psychology and social science' in The Journal of Analytical Psychology, 57 (1), 2012, pp.76–98

Carl Gustav Jung and Aniela Jaffé, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Vintage Books, 1989, p.192

Siamak Khodarahimi, 'Dreams In Jungian Psychology: The use of Dreams as an Instrument For Research, Diagnosis and Treatment of Social Phobia' in The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 16 (4), 2009, pp.42–49

David Lindenfeld, 'Jungian archetypes and the discourse of history' in Rethinking History, 13 (2), 2009, pp.217–234

The Society of Analytical Psychology

Nora Swan-Foster, 'C. G. Jung's Influence on Art Therapy and the Making of the Third' in Psychological Perspectives, 63 (1), 2020, pp.67–94

Wellcome Collection, Dreams of a patient in Jungian analysis. Drawings, 1967–1978

Caifang Zhu, 'Jung on the nature and interpretation of dreams: a developmental delineation with cognitive neuroscientific responses' in Behavioral Sciences, 3 (4), 2013, pp.662–675